index memoir -

homepage - contact me at

After our abortive Lesotho experience, I flew off alone from Cape Town to London to obtain a visa to enter Pakistan. Spie had told me that as I did not have a current French ‘Carte de Sejour’ it was not possible to get a Pakistani visa in Paris. Andy, our daughter was now based in London and we met for lunch on Sunday, but on the Monday my visa was rapidly obtained at the Pakistan Consulate. I then went directly to Paris only to find that the urgent trip had been postponed for some weeks. Cubby joined me from Cape Town at our rue Claude Pouillet apartment before I finally left for Pakistan.

Personnel from a potential French construction group of the three companies Framatome, Alstom, Spie Batignolles (covering respectively Nuclear, Electricity Generation and Civil works) travelled out to the capital city Islamabad (the City of Peace) for preliminary discussions with WAPDA (the Water and Power Development Authority) of Pakistan. Electricite de France (EDF), the national utility company were not part of the proposed construction consortium and did not, have representatives on this trip, but were involved as design co-ordinators.

I had come across WAPDA in the early nineteen sixties when I had worked in (West[1]) Pakistan on one of the World Bank financed irrigation schemes replacing water supplies which had been cut off when India and Pakistan had achieved independence from the British Empire in 1947. WAPDA had effectively been the Client and had staff representing them on the numerous barrage and canal projects – the one I was on, the Mailsi Siphon, was a barrage / siphon taking canal water across the seasonal flowing Sutlej River, a tributary east of the Indus river, in the desert near Multan the ancient city through which Alexander the Great had passed.

Towards the completion of the Mailsi Siphon project, work on the construction of Islamabad, the new capital city, designed by several famous architects and town planners, had just started. Islamabad was 9 miles from the ancient town of Rawlpindi, where I had stayed overnight when on a short solo holiday break from Mailsi site up the Kagan Valley heading to see the 26.660 foot high Nanga Parbat mountain. But floods had prevented me reaching the base of the peak. At that time President (General) Mohammed Ayub Khan, following a military coup in 1958, had lead Pakistan. After several changes in leaders and the restoration of a democratic system General Zia-ul-Haq had seized power from Prime Minister Mr Zulifer Ali Bhutto in 1977. Mr Bhutto had later been executed in 1979 despite international protests.

Although Zia-ul-Haq had died in a mysterious plane crash in 1988 and a semblance of democracy had been restored with Benazir Bhutto[2] (daughter of Zulifer Ali) now as prime minister, many western nations hesitated to become involved in a nuclear power project in Pakistan which would produce fissionable material suitable for manufacturing nuclear bombs - a sensitive issue in view of the past wars and constant friction between India and Pakistan over the sovereignty of Kashmir and other religious and border issues. Such fissionable material was possibly in any case obtainable by Pakistan from other sources.

Several technical meetings took place with WAPDA and we also met and assessed local contractors who wished to partake with us in a civil works consortium. We then flew in a brown Pakistan Military aeroplane, sitting along the sides of the plane, down to an airfield and then drove through flat irrigated farmlands (parts flecked white with salt due to insufficient drainage) for some hours to Chasma Barrage and Canal (earlier world bank projects) to inspect the nearby site. The requirement for plentiful quantities of water for condensing steam was always a significant factor in the selection of power plant sites. At the site I learnt that it was presently also the intention for a nuclear power plant to be constructed there by the Chinese with the French plant to follow – indeed an agreement had been made with both these countries in 1989. Apparently a small nuclear power plant supplying some electricity to Karachi already existed at this time.

Returning to Paris at Spie’s office we continued planning and pricing the Civil works to build up an overall price for the project. I somehow doubted whether the project would come to fruition – there seemed to be many political and financial obstacles - it was difficult to be enthusiastic. In the office the constant activity and sense of physical achievement found on construction sites was lacking. On sites it was also possible after lunch to take a break and walk outside to see progress rather than sitting at a desk and struggling not to doze off.

At this time I met an English friend Peter in Alstom’s office who was controlling the construction of a gas power plant, Kawas, in India at Surat. Alstom were having problems on the civil works construction for the plant and he approached Spie about me going on his next technical visit to India to assist in solutions and to assess possible subcontractors. I had previously been seconded to Alstom for civil works on projects both in South Korea and Sumatra - which had gone well. Spie agreed - seconding staff was usually profitable and Alstom not Spie would be responsible for construction risks. Spie hoped to put several people on site.

Before leaving for India Peter and I went by train to Alstom’s original manufacturing base at Balfour where the civil specifications were being written for works still to be subcontracted. The drafter of these civil specifications, a French mechanical engineer, seemed reluctant to make corrections put forward by me to English language and civil works content. On our return journey we stopped at Nancy where the civil designers were based – the same company had designed the Sumatran project on which I had worked. Their design representative was also to accompany us to India.

We flew off and landed in Bombay and then drove to a modern hotel in a battered ‘Hillman’ taxi - such Hillmans were the only cars manufactured in India for some decades. As requested by SB, I briefly met their expatriate representative at this same hotel. SB had been working on a contract for a major sewer outfall for Bombay discharging into the sea, but had apparent recently aborted this underwater marine contract because of physical difficulties. Their representative was now busy tying up loose ends, selling off equipment and disestablishing - claims and counter claims between SB and their Client were in progress.

Alstom’s site, which we went to by train a few days later, was at Surat in the state of Gujarat about 200miles north of Bombay. The British had established their first trading post in India at Surat in 1612 – Surat had been a thriving city manufacturing and exporting cloth and also gold. But later Bombay had taken over as the main British settlement on the east coast. At the main Bombay railway station we were surprised to see moving electric suburban trains crowded with passengers with access doors wide open and some people dangerously clinging on outside the carriages. Our train to Surat was an electric long distance train with side corridors and compartments - bunks could be lowered for overnight journeys – we travelled in daylight.

The train passed across numerous rivers, most of the bridges’ structures were below track level and we looked out of the windows seeing only water below - an eerie sensation – there appeared to be nothing to stop trains from toppling off the tracks if they were to derail. Further all the train windows were heavily barred to prevent theft from outside, but at the same time would prevent us escaping from a watery coffin. During the journey attendants (whether they were railway employees or not was not clear) plied us with food, including simple tasty curries and chapatis, and strong milky tea.

On the site some piling work had already been done - but there had been unforeseen problems. The piles were cast in place, bored piles excavated by grab and chisel through heavy liquid bentonite ‘mud’ which prevented the surrounding soil from collapsing into the excavated shaft. At the top of the piles local contractors normally used a steel sleeve about 1,5m deep to start the pile off and to prevent the upper soil collapsing. On this project a specialist French company who had done ground investigations said there was an underground ‘stream’ at about 4m below the surface which would damage the wet pile concrete. They had insisted that the normally used 1,5m long top sleeve be extended to 8,0m depth to protect the wet concrete.

After the pile was fully excavated a prefabricated reinforcement cage would be lowered into the bentonite. The pile would then be concreted through a tremi-pipe displacing the liquid bentonite progressively upward. The top steel sleeve was then removed for reuse using the tripod set over the pile and a winch. But a problem occurred - it was found, that as a 8,0m long sleeve had been used, the concrete had already partially set in the sleeves lower half while still concreting the top - its extraction thus became prolonged and difficult and damage to the concrete was also feared. A more rapid supply and placement of concrete together with speedy tube extraction by a tracked piling rig would have been one solution but neither was available and would have increased costs significantly.

For future piles to be driven it was suggested to the ground investigation company that a 1,5m long sleeve be reverted to and that stream water damage was unlikely – but despite the problems they insisted on an 8,0m sleeve length. To resolve this impasse I suggested that a concrete admixture, retarding the set of the concrete for a further few hours, as this would enable the 8,0m sleeve to be extracted before concrete set occurred. Several months of delay had occurred through these piling problems and it was decided to call for new piling subcontracts tenders for the balance of the piling work. The requirement for the use of concrete set retarding admixtures was written into the specifications and later was successful in practise.

We left Surat and visited construction sites of several larger local civil contractors both in Bombay and Delhi to assess whether they would be able to do the main civil works (subject to competitive tendering). The quality of work done in India seemed to vary considerably from very good to very poor, as indeed did attitudes to safety. We had to ensure that civil contractors employed would do satisfactory jobs and had resources available within their company. Much Indian construction work at this time seemed to have been hindered by restriction on the import of construction plant from abroad – there was a reliance on sometimes inadequate locally made plant and abundant but somewhat unproductive unskilled workmen. Eventually for main civil works a company, Larsen and Nielsen, which had been started by Danes during British colonial times was selected – at least one of the Danes had stayed in India during the second world war - a return to Denmark occupied by German forces was not feasible. It was hoped, that although the original owners had long since departed, the now Indian management would still have a disciplined approach to work.

|

|

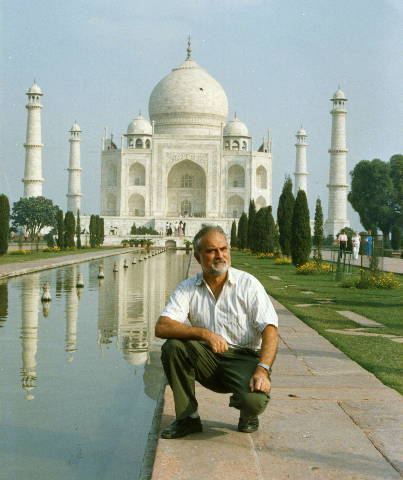

Me posing in front of the Taj Mahal |

While in Delhi, on a Sunday rest day Peter and I took a fast local train south to Agra to see the Taj Mahal. This mausoleum built by the Mughal Emporer Shah Jahan to immortalise his favourite wife Mumtaz Mahal who had died in childbirth in 1631 is an inspiring monument. On leaving the inevitable hawkers selling souvenirs and postcards buttoned on to us. One hawker offered postcards showing erotic statues from various 13th century Hindu temples in Khajuraho miles away confirming that human sexuality had not changed much over the years – but had nothing in the least to do with Agra. Later in the town I bought some colourful woven (not knotted) cotton darris (carpets) for our apartment.

Back in Paris Alstom and SB agreed a site organisation both for controlling and advising the contractors on the construction of the civil works including engineers and a quantity surveyor. Apparently Alstom’s site manager had already employed another French company to control civil works but the agreement had failed soon after implementation – one of their local engineers from the then unsettled Punjab region had remained on the project.

In about mid November 1990, Cubby and I flew to India together. We arrived in Bombay after midnight, went directly to a hotel, showered and slept for about four hours before we caught a train to Surat at 7.45am. The train started but we then sat roasting in the heat in the middle of nowhere for three hours due to a power failure. Only then did we discover that we had been booked on the slow train normally taking 6½ hours compared to the 4 hours on the express train I had travelled on earlier. We were crammed into a compartment with 12 people rather than the intended 8 - the train was chock-a- block with many standing passengers. Our seats were not reserved and we felt we might lose them if we tried to walk down the corridors We had unfortunately brought no bottles of water and had to buy warm sickly sweet fizzy drinks to quench our thirst.

With aching heads after 9½ hours cooped in the train we eventually reached Surat, and not being met, took a taxi to the pleasant and restful Rama Regency Hotel some way out of the centre of the town on the left bank overlooking the Tapti river. Jet and train lagged, we slept very soundly our first night. The hotel had the usual ‘western styled’ coffee shop where we usually breakfasted and dined, but it also had a more formal restaurant where we enjoyed curried vegetarian dishes served in small metal bowls (talis) accompanied by chippatis, paratas, naan bread and rice.

Over weekends in a field nearby the hotel a formal cricket game with players dressed in white would usually be in progress, but during any day at any time we would usually see youths playing informal knock up games of cricket, some in the centre of the town near a statue erected to commemorate Gandhi - there was much enthusiasm for the game, possibly one of the most significant legacies of the British Raj.

|

|

|

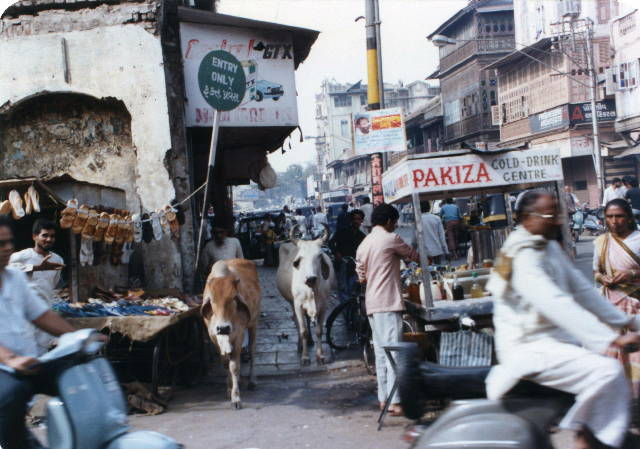

Street life in Surat |

|

|

|

|

Domestic chores - washing clothes at river - drawing water from well |

|

We frequently saw cows, revered by Hindus, in the town streets, they seemed to ignore lush natural greenery and perversely seemed to ‘graze’ at rubbish collection points, often gnawing through plastic bags to get to some succulent household scraps.

Cubby recalled that this was the same Tapti river which her mother Mercia and uncle Manne as children had crossed on the backs of swimming horses years earlier when her Swedish grandparents had been missionary teachers in India. On my first work free day we hailed a motorised rickshaw and tried to reach the mouth of the Tapti River in hopes of seeing the sea. But roads only went up to a flat plain evidently stretching to the unseen sea and apparently silted river mouth ahead of us. We came across men giving camel rides and hired them hoping that we could still get to the sea, but after a while the ground underfoot became boggy - an incoming tide - and the camels shied away and refused to go further.

Surat appeared to us to be ¾ a slum / shantytown but there were some substantial buildings and new apartments were being constructed everywhere. We were informed that Surat was after Antwerp the 2nd biggest diamond-cutting centre in the world, something not obvious when driving through the town.

Cubby found that there was a Protestant Church with some services in English at 6-30pm every Sunday evening as there were apparently Christian strangers from other parts of India who did not speak the local language. The church had been established 150 years ago by Protestant Irishmen and this was an important anniversary year. As I was not happy with Cubby travelling alone in the dark to and from the church I, although not a churchgoer, accompanied her. There was a small enthusiastic congregation of 10 to 20 people for the English services -I found the sermons somewhat long and my tuneless singing did not improve the piano-less hymns and poor acoustics amplified by squeaking loudspeakers. Other native language services were well attended. Cubby was the keen Christian but I as a male was misidentified as such.

To get to the site on the far bank we travelled in small microbuses on narrow city roads upstream reaching a narrow bridge – a journey through nightmarish traffic – cars, lorries, ‘took – tooks’ (motorised rickshaws) and scooters all belching fumes and with hooters blaring, also carts drawn by donkeys or bullocks frequently slowed down the pace. If the traffic came to a halt our driver did not hesitate to swing into the opposing traffic lane if it was momentarily empty and to then force his way into the queue if a vehicle approached – nerve-racking experiences. A new concrete bridge intended to relieve the congestion had been under construction for some years but progress had apparently been slow possibly because of lack of funding.

Although Alstom’s site manager had told their Client that a housing colony would be built near the site for expatriate personnel on the project and that after the project was completed this would be given to the Client for his operating staff - little had started. Cubby was asked to see what local accommodation was available for us and spent many weeks looking at houses and apartments and what furniture could be purchased locally.

Invited by one of the businessmen who had shown her various apartments and what furniture was available, Cubby visited a beautiful older house lived in by his family of 6 brothers with their wives and grown children. Fore and aft of the house were very narrow lanes - rather claustrophobic. The attractive front of the house had intricately carved wooden beams blackened by the oil used to preserve them. The lower level was a ‘godown’ (store area) stone floored and cool where in olden times they kept large urns of water and other provisions. Above this there were 3 upper levels, linked by steep almost ladder like stairs, with an internal shaft letting the light in to access ways and internal rooms. Apparently during the 3 month monsoon period this well is roofed over to keep out the rain. Each brother’s family occupied half of a level stretching from front to back living in apparent harmony – something difficult to imagine in a western environment of insular families. Later I was invited to return with Cubby to this house where we enjoyed a traditional Gugarati meal and afterwards watched from the roof a magnificent panoramic view of the town with colourful kites darting in the sky. It was an annual festival and participants were trying to intercept other kites and cut them down with their abrasive strings.

The Alstom site manager was at this time also living in Surat with his wife, a petite friendly woman who had always worn very highheeled shoes and now with calf muscles set was virtually unable to walk without them. She spoke virtually no English and Cubby only a little French. Almost daily he would send his large chauffeur driven car back home from the site to take his wife out shopping. Cubby was frequently asked to accompany her mainly to tailors and shops and sometimes acting as the second chain in a translation process from native speaking shopkeeper to English speaking Chauffeur to French.

It was apparently one of the two bridal seasons of the year and shops were filled with parties of women sitting and drinking cold drinks while shop assistants threw sari lengths of good quality silk over the counters. The car would return to the site fairly late in the evening to pick him up well after we had finished our day’s work, but to compensate for this he seldom arrived before 10am in the morning – in this he followed the practise of many important managers.

At this time the Congress party which had ruled India since Independence from Britain in 1947 (and had mainly been led by Nehru, his daughter Mme Gandhi or her sons), had fairly recently been disposed by a coalition of right wing Hindu parties. It was thus not too clear how India would develop under this new regime. There seemed to be a background of intercommunity violence between Hindus and Muslims reported in the many local English papers as occurring in several places, including Ahmadabad (also in Gujarat not very far from Surat). Community relations were then also being made worse by fanatics wishing to take over the ancient Muslim Mosque of Babur in the Hindu holy city of Ayodhya and to convert this into a Hindu temple. Further away there were Sikh separatism movements in the Punjab and the continuing problems within Indian Kashmir where some wished to join Pakistan.

I found that although the Times of India was written in clear English, other local English newspapers incorporated many Indian words, and were difficult to follow. During this period we also felt rather unsettled by international affairs as the UN forces led by the Americans were preparing to throw Iraq out of Kuwait (which they later did in 4 days starting on 24th February 1991). We were unsure what effects this would have both in India and Europe.

Before leaving Europe, Alstom had given us the sites Post Office Box number and we told family to address our mail there. When nothing came after a few weeks we were told that the site had not been using the Box number. We insisted that the company messenger checked to see if any mail had arrived for us which indeed it had – a strange but not unique situation on this project. We also later found that some of Cubby’s earlier letters to her parents had never arrived, she, too trusting, had asked a messenger to buy stamps and post them rather than pasting on the stamps herself.

Gujarat like most Indian States was dry but foreigners, regarded as being alcoholics, could obtain permits to purchase alcohol – indeed we were allowed for the two of us for one month 40 ¾litre bottles of beer, 4 bottles of wine and one bottle of spirits – more than we could possibly drink in a month – but no doubt some expatriates could consume more than their allocation.

Other SB staff arrived within weeks as bachelors but some intended to bring wives or partners out later. They were temporarily housed in a guesthouse in a rather unsanitary area near a rubbish tip on the right bank in which warthog like pigs scavenged for food. They avoided the daily struggle across the bridge but it was still a considerable distance from the site further downstream. After some weeks, Alstom sent an expatriate doctor to inspect the sanitary conditions both of the bachelor quarters and the future intended housing colony. Presumably his report was not favourable as Alstom then found some newly constructed apartments built for a large manufacturer closer to the site and rented these until their own housing colony was completed. Some of Spies staff after their experience of Surat and the site of only a few weeks decided that it was not a suitable place to bring their wives. Indeed we were not altogether surprised when about 6 years later we heard later that there had been one of the few modern outbreaks of plague in Surat. We recalled the perpetual colds all newcomers to Surat appeared to catch and recatch.

Alstom organised a staff dinner at the bachelors quarters for Christmas Eve 1990 – not that many of us felt particularly celebratory or enthusiastic despite eating traditional French Bouche Noel (Swiss Roll shaped as a log and coated with chocolate) – we all were probably feeling a little isolated and unadjusted to a strange environment.

On Christmas day we were asked by an Anglo Indian couple, Mr and Mrs Williams from the local church, to dine with them at their apartment on Ghod Dhod Road (Horse Racing Road). The meal was one of the best we ate in India. We started with a nice fresh tomato soup, followed by mutton bryani, chicken curry, a delicious thin dhal, cooling raita (cucumber slices in yoghurt flavoured with mint and coriander) and chutney and dosai (pancakes made from ground white beans). This was followed with ice cream and an Indian Christmas cake (a sponge - a bit like a honey cake). To cap this culinary experience we finished with gorgeous barfi (a fudge made from greatly reduced boiling milk, sugar, pistachio nuts and cardamom with silver leaf on top). Later in the evening we attended the carol service at the church including many Gujarati Christians and others from as far away as Kerala (where St Thomas[3] brought Christianity to India in 54AD)

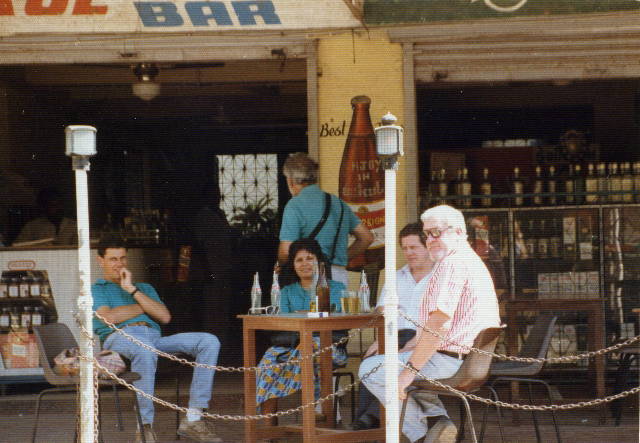

Over one weekend most of SB staff went by road southwards to Daman[4], once a Portuguese colonial enclave reverting to India in 1961. The roads there were narrow bumpy and congested and progress was slow although the distance was not far. It appeared that there had been little road building since the British had left in 1947 – in places we saw people on the roadside breaking stone to make aggregate for repairs rather than mechanical crushers being used – this approach, apparently to give people employment, would not improve the road network rapidly. Our initial attraction to Daman had been that it had remained a ‘wet’ area where alcohol could be purchased and drunk freely in bars and hotels.

|

|

|

|

|

Christian church and graves within fort walls at Daman. Drinking at a Daman 'pub' with expatriates from the site. Fishing boats at anchor. |

|

|

|

|

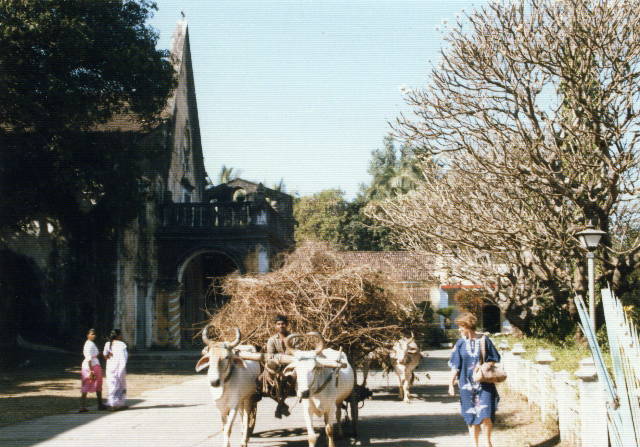

Poster asking for the removal of the dowry system. Cubby alongside cart pulled by bullocks. |

|

But what Cubby and I actually appreciated was that it still had two colonial old forts on either side of the river dating back to 1559. The south bank fort was very big and enclosed attractive administrative buildings and a typical Iberian cathedral and churches of a younger vintage. We wandered under huge trees which shaded the streets and dappled the dark cream and rust buildings. We also walked right around the ramparts of the forts looking down at cricket games in progress and at elaborately tomb-stoned graveyards. The town was right on the coast, without the endless mudflats of Surat, The sea was a turbulent brown but fishing boats were coming in and out. In early mornings and evenings the sandy beach was used as a latrine by squatting anonymous figures with incoming tides acting as an efficient flush.

On site when excavation started for the construction of the turbine and generator footings most of the already formed piles were found to have exposed reinforcement in parts, the extraction of the 8m long sleeves had disturbed and damaged the concrete cover – this could affect long term durability if there was reactive oxygen in the surrounding ground water causing corrosion to the reinforcement – an embarrassing situation, particularly as good quality work was necessary.

The French ground investigation engineers had also required that the cast in place friction / end bearing piles should have a grouting tube provided so that they could be grouted at the toe to fill possible hollows or to solidify any loose soil material. Tubes thus were pre wired to the rebar cage to provide a grout passage. Grouting was apparently something the specialist Indian piling contractors did not usually do on their standard piles. A few days after the concrete had hardened the pile was to be grouted - in theory the grout pressure was to be sufficient to break the temporary seal/valve at the bottom. In practise this had not worked on most of the piles as the seal was surrounded by some centimetres of hardened concrete not breaking away.

When I came to site we succeeded in pre-breaking out the seals / concrete with a long steel bar hammered up and down prior to grouting at the pile toe. Fortunately piles did not fail under load tests even where grouting had probably not been properly done earlier.

It seemed that the ground investigation consultants, who had changed what was normal piling practise for such piles in India, had created problems which both Alstom and their local specialist contractors had difficulty in solving. By SB staff solving these problems, Alstom site manager may have felt that his earlier management had been shown as being inadequate.

As was my normal working practise, I had started holding regular weekly meetings with the piling and civil works contractors and carefully wrote minutes recording what actions they were required to take. The Site Manager, who did most things verbally (the written word can be incriminating), tended to criticise my approach and reported unfavourably back to his head office on present civil works progress and barely started under my direction. 7 months delay had already occurred on the works before my arrival and it seemed that I would be a convenient scapegoat for likely future delays.

This was a totally unsatisfactory situation. As I did not think this would improve after I had spoken to Alstom’s visiting managers who stood by their site manager, I decided to leave the project. There was a standard clause in my contract of employment allowing me to withdraw from the project within some months if I found the working environment unsatisfactory. Unfortunately because of disrupted lines, telephoning this decision to SB in France was not possible and my faxed decision to leave also apparently did not arrive. However, having made this rather drastic decision, I was not unaware that I might lose my job with SB on my return to France. I started looking at advertisements for jobs in construction journals and hurriedly wrote off a few letters.

We moved into the new temporary apartment closer to the site on the 30th January 1991 and just one week later we packed up our belongings and caught an early morning train to Bombay. On arrival arranged our flight back to Europe on the next day. That afternoon we wandered around Bombay’s shopping area whose tiled pitch roofed low rise buildings and shops we felt had hardly changed from colonial times 50 years early – a pleasant time warp.

[1] East Pakistan later had left the country and became Bangladesh in 1971. The ‘west’ description then became redundant.

[2] Benazir Bhutto was defeated in the October 1990 general elections some months after our visit.

[3] Alleged to be ‘doubting Thomas’ within the twelve apostles when told of Christ’s resurrection

[4] Just under ½ way to Bombay

index memoir -

homepage - contact me at