index memoir - homepage - contact me at

I flew on a day trip to the enchanting Channel Island of Guernsey to see the site and investigate housing possibilities. The Site Manager Reg Titford was already established in a site office overlooking the harbour with a view of drilling, blasting, and dredging works from pontoons being done by a subcontractor to deepen[1] the harbour. Christiani and Nielsen (CN), in consortium with a local contractor Gamble[2] and Blair, were responsible for executing both the detailed design and construction of a container handling port within the old existing granite block harbour at St Peter Port.

In Guernsey there was a two tier housing market – local and foreign. The local market applied to persons whose families had been born on the island and prices for these houses were generally reasonable - on par with property prices in England at that time. The foreign market was open to outsiders who were willing to pay high prices for nominated generally luxurious houses in limited supply. However, we, sponsored and deemed essential to the island’s economy, could buy on the local market with the proviso that we must sell on the local market when leaving.

I immediately viewed a four bed-roomed bungalow in St Martins on the higher land on the south side of the island. It was on a narrow sunken lane virtually in the country with a few ‘glass’ houses for tomatoes in the vicinity. Without consulting Cubby I bought ‘Timber Tops’ on Les Hurettes Lane for £8500. This house, like most of the houses in rural areas of Guernsey, was not on mains drainage – wastewater discharged into a tank needing periodic pumping out by a cesspit truck, otherwise it was spacious and reasonably modern with oil fuelled central heating.

We sold our house in Frodsham for a modest profit. The family (minus dad) moved for a short time to Cubby’s parent’s apartment in London. I started work in Guernsey, staying in a hotel until the finalisation of the house purchase and the arrival of our belongings. I then flew back to London and with family drove to Weymouth in our Volvo and boarded the over night ferry – the car was crane lifted onto the boat – it was not a roll on roll off ferry.

We settled in quickly that July of 1970 with Cubby in an advanced state of pregnancy. I bought a cheap old rear engine blue Renault as a second car for commuting the short distance into St Peter Port to work, while Cubby drove the Volvo taking the children to school. The roads were generally very narrow, so narrow indeed that buses on the Island were cut down and made less wide than buses on the mainland.

Nicky entered the Grammar School at St Peter Port and Karen and Christopher went to the local St Martins junior school. Young Andrea remained at home for some time until she was sufficiently old to join her siblings. Karen and Andy enthusiastically joined in ballet dancing activities at school and Nicky continued horse riding.

|

|

|

|

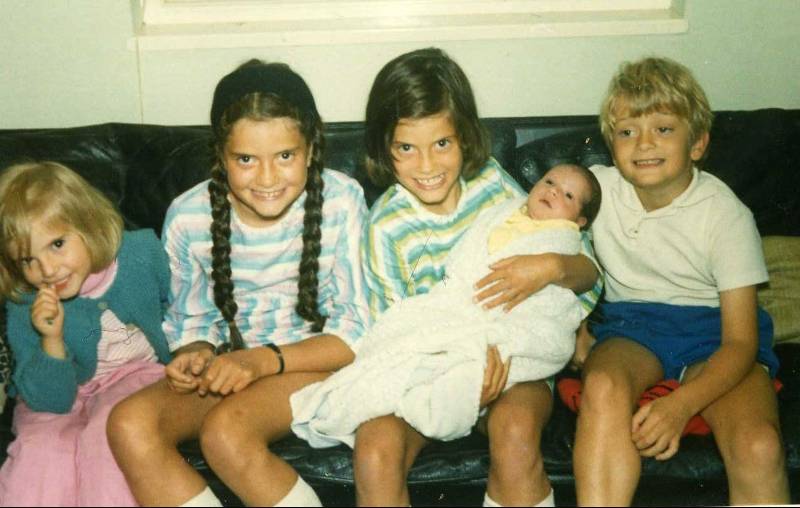

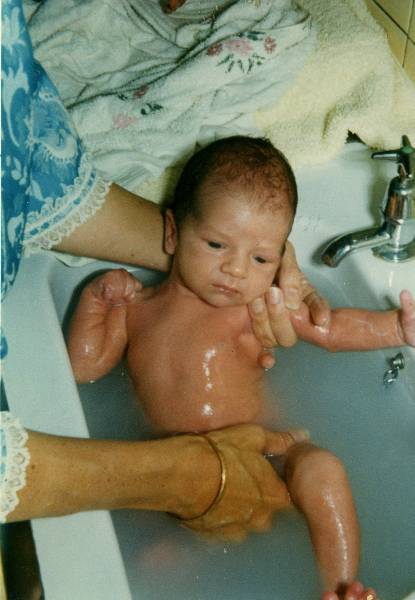

Benjamin born 26 August 1970 (same day as his elder brother Christopher), about 11 days old in first two pictures. Children on sofa with Karen holding Ben. Ben having a bath in basin. |

||

Our second son and fifth child Benjamin was born on the same day as his elder brother Christopher had been in Pakistan 7 years earlier – on the 26th August 1970 at the Maternity hospital in St Peter Port. Cubby telephoned the news to me ‘babysitting’ at home. After visiting her and the new arrival, we celebrated both birthdays with not very inspiring pilchards in tomato sauce – I was a very limited tin can opening cook.

|

|

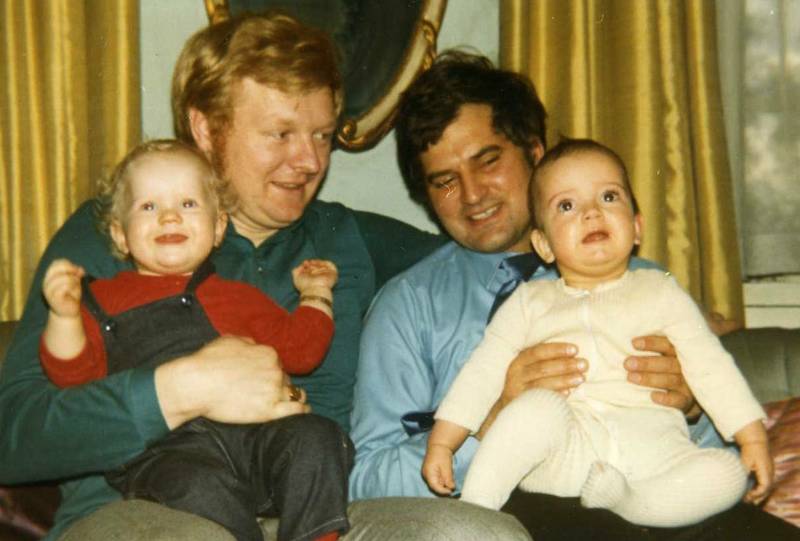

Mercia and Aage join us at Christmas in Guernsey. Ole with his second child daughter Alexandra (Sandy) me with Ben in Aage and Mercia's London apartment |

|

We started driving vertical and inclined steel ‘H’ piles[3] behind the existing stone quay walls. These piles were both to support a ground beam under the edge of the future suspended decking over the water and to resist boat-berthing loads. Foundations for two future stiff legged derricks were also piled. These cranes, used initially on construction works, would later be used as permanent cranes for unloading and handling containers.

One of the derricks had it’s kingpost just beyond the existing quay in the water and a large base was formed and then concreted under water using tremi concrete – that is very flowable concrete placed through several continuous vertical pipes and not vibrated. Lifting the tremi pipes above the liquid concrete surface would cause concrete to drop through seawater and the cement to segregate, so they had to be carefully lifted always keeping their ends embedded under the concrete surface. The base took 12 hours to concrete and perfect results were achieved as could be visually seen when the top of the base was occasionally uncovered in very low spring tides.

The large fluctuation of tides of up to 12 m height in Guernsey completely changes the character of the seashore from low to high tide, and we had to be constantly alert when working in or near the sea as changes in water level could rapidly cover or destroy work being done.

The tidal ‘splash zone’ subject to regular wetting and drying is the area where there is the greatest potential for rebar corrosion should concrete cover to rebar be permeable or too little. A much earlier built concrete jetty adjacent to our works, where the ferry boats docked, was at that time undergoing extensive repair (by other contractors) to its supporting columns by guniting[4] over shot blasted corroded rebar in the splash zone.

Possibly, with present day knowledge, the reinforced concrete work on our project, especially the supporting columns in the splash zone, would have been better done with either stainless steel rebar or with rebar, either galvanised or treated with epoxy, but these were not then available or commonly used. The rebar also would have been better tied together with stainless steel binding wire (if this had also been available) rather than the mild steel binding wire[5] - wire off-cuts falling onto exposed surfaces and possibly not totally removed before concreting could rust later. These measures would have given more protection and corrosion of rebar with expansion and spalling off of concrete cover ultimately weakening the structure[6] definitely eliminated. At this time however, reliance was only placed on the quality of the concrete and a sufficiency of cover to prevent corrosion, but both factors, if below standard in some areas, could possibly permit water penetration. Many earlier marine structure had however been built without these measures before and since this time.

|

|

|

|

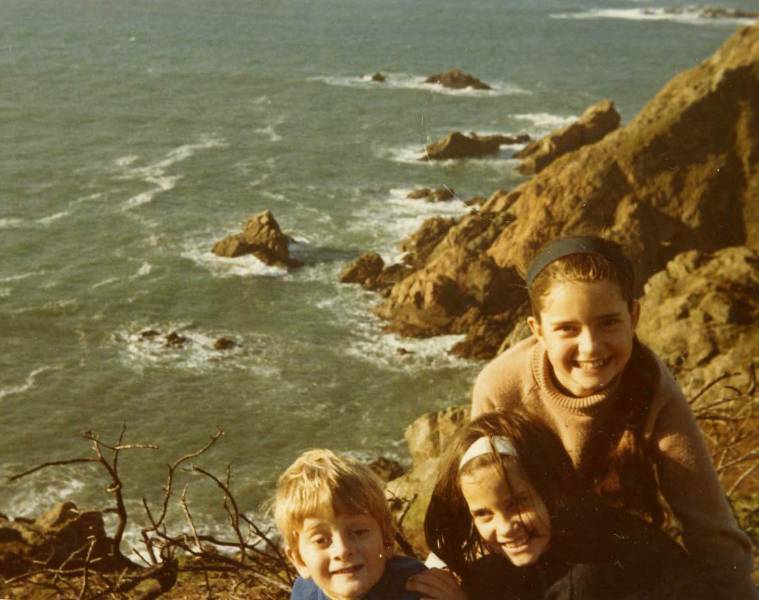

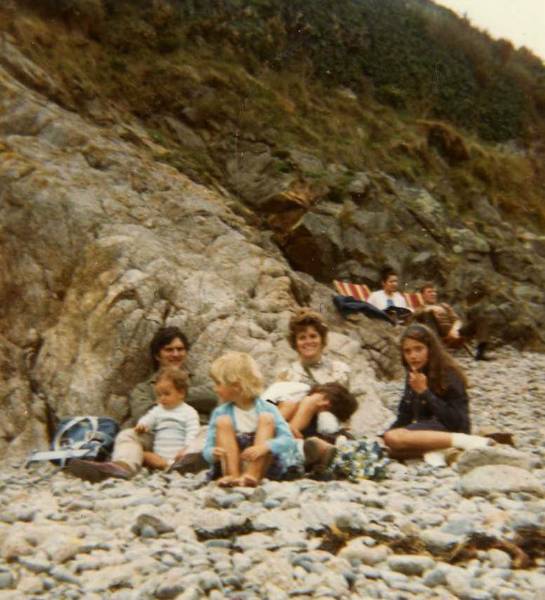

Guernsey's rocky shores and beaches |

||

On the south side of the island not far from our home there were rocky cliffs above small sandy bays often only exposed at low tide. We sometimes reached these bays on paths snaking down the cliffs[7]. On the beaches we had to be careful not to stray too far and risk being cut off by the incoming sea. Such bays, generally used by the more adventurous, were pleasant for picnicking in relative solitude.

|

|

|

|

|

|

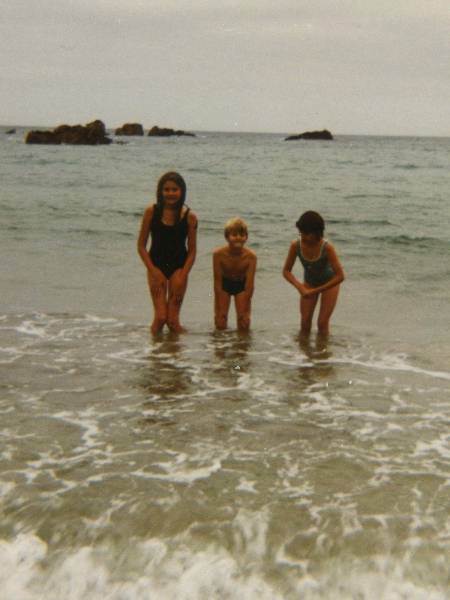

Now there were five - Andrea, Christopher, Nicky, Karen and Benjamin |

||||

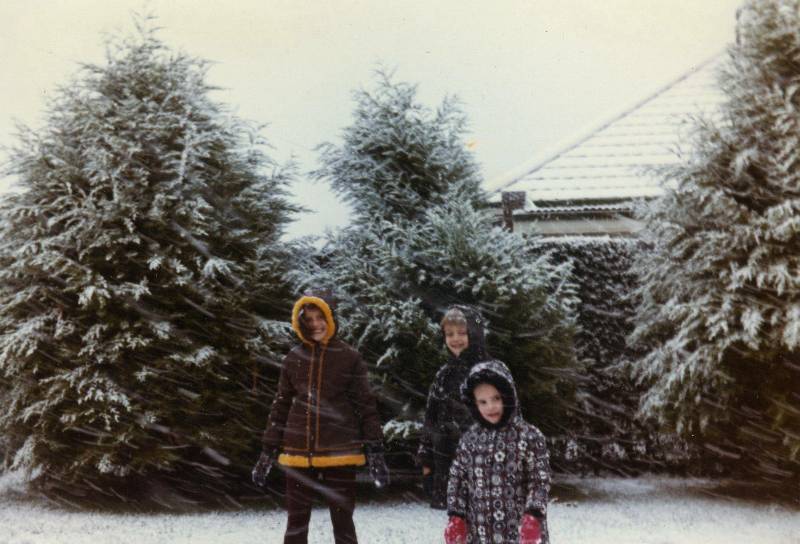

Not many of the inhabitants spoke French, we heard the local patios only on occasion in small local shops away from St Peter Port. The island’s buildings still maintained a Gallic character despite the more recent English influence. Victor Hugo had gone into exile here during the last century during a period of political difficulty in France. The climate was also more pleasant than on the England mainland with an earlier Spring seasons, later Autumn seasons, and sunnier Summers. Despite this we had snow in which our children happily played at both Christmas seasons 1970 and 1971 but which also caused the closure of the airport.

The flora was also different from the English mainland – it is unsurprisingly closer Brittany in France. We also saw South African wild figs (a succulent plant) apparently having taken root after being washed ashore from a shipwreck.

The island had gone through waves of different types of economic activity. Tomatoes were now being grown in heated hot houses for the British market. We could get surplus tomatoes cheaply and bottled delicious chutney. Freesias were also being grown under glass and daffodils in open fields – many Dutch growers seemed to be about. In earlier times grapes had also been cultivated in greenhouses but this activity had now largely ceased possibly because French wines could be bought without the addition of tax. Indeed inhabitants did not have to pay income tax[8]. Large granite quarries had been exploited at one time near St Sampson harbour on the north east of the island. Granite had been shipped from this harbour to Europe – much of the stone was in small stone blocks – ‘pave’ as used on cobbled streets in Belgium and France before the advent of bitumen Macadam.

Gamble and Blair had their offices and yard in one of these former quarries. Here they produced both precast beams and soffit slabs to be used in the suspended container berth decks over the water. At the site itself we precast larger elements – hollow cylindrical concrete columns to support the deck. These heavy columns were cast horizontally in single lengths just behind the new berth. The columns were lifted and rotated vertically and placed over steel piles driven earlier where there was no rock. In positions where there was rock piles were not necessary and the columns were placed and concreted into sockets excavated by divers[9] under water using pneumatic picks and airlifts. The hollows in columns (both those with and without piles) were then, after sealing them at their ‘toes’ and pumping the water out, concreted in the dry.

Generally Gamble and Blair supplied most of the foremen and labour required on the project, but CN Londonís office recruited a General Foreman to control the marine works - a South African who had recently immigrated to Britain. Unfortunately after some months it was found that his ability did not match his CV, nor had checks been made with his previous employers - he was ineffective and was fired. It was then found that he had borrowed money from other staff on the site and not repaid it. A local resident and reliable Gamble and Blair employee John Sadler, a Scotsman, took over.

|

|

|

Barbequing in sunny weather, but not always warm - sometimes snowy and cold |

||

Although we knew that our time on Guernsey would be limited (the job was on schedule) we paved an area at the back of the house and built an open air ‘braaivleis’ (barbeque) fireplace to eat and drink with many friends and relatives visiting from both England and Scandinavia. We also nurtured and harvested pounds of raspberries from canes in our garden and collected blackberries when walking along the cliffs close to our home.

Reg the site manager, who had dealt with most of the political aspects initially with the Client, our consortium partner, and the nominated dredging subcontractor, somewhat reluctantly retired when these aspects had been largely sorted out – there was apparently nothing really available for him to do in the London Head Office. He planned to retire to the nearby island of Sark where he had spent many pleasant holidays. I took over as Site Manager, but really continued my function planning and directing the direct field construction works.

We were honoured by a visit to the job of CN’s owner Alex Christiani (son of the company’s founder Rudolf Christiani) and a contemporary of my father in law Aage Brink, his then London Manager - they had both studied Civil Engineering at University in Copenhagen. Mr Christiani had belatedly married and his younger wife who accompanied him was now expecting his son and heir.

During our last Christmas 1971 on the island our 11year old daughter Nicky visited Cape Town at the invitation of her aunt, my sister, Ruth. She returned with glowing accounts of her holiday making me nostalgic for my birthplace and family. On seeing an advertisement in the British press for Civil Engineering staff in Cape Town I applied and attended an interview in London. I was offered a job and decided to accept it despite some reluctance from Cubby who would now be leaving her family, comparatively recently returned to Europe from Cape Town after 30 years sojourn in South Africa. I also rather naively (or wishful thinking) accepted the interviewers statement that there were signs of apartheid being relaxed in South Africa.

Another factor, influencing me, was a desire to work in a different company to that of my father in law. He had greatly assisted me on going on several very interesting projects in different countries, but if I progressed with C N in Britain the charge of nepotism could become stronger if I were preferred for more senior positions over others. Another factor was that bringing up a family with five children would seem to be difficult in Britain for a Civil Engineer probably having to travel from one relatively short term project to another – one could not guarantee a permanent stay in a house in London or elsewhere – houses in any case seemed expensive. CN put forward possibilities of working as a ‘schedule engineer’ in London or possibly in one of their subsidiaries in South America, but I turned it down – my mind was now made up.

I started handing control, prior to departure, to my pleasant and extraverted deputy John Wallis[10]. We sold our house, packed up and shipped belongings and our Volvo estate car (I had purchased a newer tax free one on the Island) to Cape Town. Cubby and children returned to England and spent 3 weeks at her parents fairly newly acquired and renovated house in Oxted – they had tired of the bustle of London - I continued for my last weeks staying in a hotel in St Peter Port and after bidding farewell to friends and colleagues temporarily joined them in Surrey.

[1] This would permit the use of larger ships and also make berthing possible at lower tides. Dredging apparently revealed some armament relics of the Second World War fortunately not exploding – the Channel Islands had been occupied by Germany. Moorings for smaller boats and yachts in shallower harbour areas had the sandy bottom exposed at low tides with boats resting on it. There was talk of building a yacht marina with tidal locks to avoid this but I am not sure if this ever went ahead.

[2] Mr Gamble, an Irishman long resident in Guernsey, had founded and still ran his company - Blair had left the company.

[3] ‘H’ Piles of corrosion resistant steel

[4] Sprayed on cement mortar

[5] Today stainless steel binding wire is used in most ordinary reinforced concrete work (not only marine structures) to minimise the possibility of corrosion defects.

[6] Whether any significant corrosion has occurred over the past 30 years on this work is not know to me. The liability of the contractors In those days for possibly defective work was usually restricted to a number of years, but some years later standard Conditions of Contract were altered and liabilities for defective workmanship or design were not time barred. Other measures to minimise possible Corrosion could have been the use of air entrained concrete or concrete with fine pozzolanic material added to the cement – but this was not often done in the UK at that time as it was more expensive. Cements used in Belgium on my earlier E3 Shelde Tunnel project incorporated blast furnace slag a pozzolanic material in the cement, which indeed was cheaper there.

[7] On one occasion on these paths we espied Enoch Powell and his wife visiting the Island – Mr Powell, a Member of Parliament, was notorious at that time for a widely reported speech referring to ‘rivers of blood’ arising through racial conflict if coloured immigration into Britain continued unrestricted.

[8] The Channel Islands, Jersey and Guernsey, each had their own system of government independent of the UK Westminster parliament.

[9] The several divers employed for this, in their spare time gathered Ormer shellfish – delicious when braised and eaten.

[10] We were perchance to meet again about 12 years later in the early 1980’s when he was working in Singapore for an international piling contractor and I was working across the straits in Johor Bahru in Malaysia on the construction of a power plant.

index memoir - homepage - contact me at