index memoir -

homepage - contact me at

Cubby and I travelled to Lohals in Langeland to celebrate her father’s eightieth birthday on 1st May. He now had a new partner, a friend from his schooldays, Fifi, a bright intelligent woman, the widow of a medical doctor – sensibly they did not plan to marry. After a few days I caught a train in Copenhagen and went to work for several weeks in Baden, ABB’s Swiss Headquarters, to become familiar with the organisation and the project,

On my first free weekend surrounded by a crowd of older people, I bathed in the hotels hot springs flowing into a series of large swimming pools. After a short train journey, I walked in pristine Swiss hills and around lakes surrounded by chalets.

ABB’s English organisation suddenly called for me to go directly to the project site in Deeside in Wales[1] not far from the ancient Roman walled town of Chester in England. Preliminary works were starting and I was needed to supervise this earlier than anticipated.

ABB’s Swiss company, under a turnkey contract, was to design and supply the civil works and mechanical and electrical equipment for the Deeside power station[2] project for National Power PLC all within a tight schedule of 33 months. This was planned with considerable overlapping of ‘civil & building’ with ‘mechanical and electrical’ (M&E) works. Any delays in civil works could delay following works and exacerbate interface working and possible damage to equipment and claims could arise from following M&E contractors.

Their local partners NEI[3] ABB, based at Newcastle on Tyne, were responsible for subcontracting both the civil works design and the civil construction works itself. Later they would also place erection and installation subcontracts for Mechanical and Electrical plant for the major turbines and generators coming from abroad. Head office staff in Baden was paired with staff at Newcastle to ensure communication and common objectives.

Before going to the site at Deeside in Wales I went to Newcastle and was briefed on what was required from me. Later in Wales we checked into a pleasant new hotel near the site and had a series of start up meetings with the Client, the preliminary works contractors and other parties. I was then left on my own with the already selected preliminary works and piling contractors.

On my first free weekend we had an important engagement in France, I flew to Paris, met Cubby at our apartment, hired a left hand drive car and then attended the wedding of friends Peter and Kumju at the Maire of Bandoufe near Paris. We left the celebrations still going strong, dancing at 3-30 in the morning, and returned to Paris and flew back to Manchester the same day.

The works were sited on the slag tips of an old steel plant. The slag, included large lumps of waste iron and other materials, had to be excavated and replaced with sandy soil through which piles for the plants foundations could penetrate. As the slag was regarded as being mildly contaminated, it was stockpiled elsewhere on the site itself – removal off site would have been very expensive. Later during the project we came across further more contaminated materials (not uncovered by limited ground investigations) – these were disposed of legally in offsite special lined dump pits which preventing seepage into ground water.

Roads, services and site offices had also to be established to provide access and power for major civil concrete foundation and other works. In principle a good concept although later we found that the buried temporary services often clashed inconveniently with permanent drainage and services. The offices provided appeared to be very large, but still had to be expanded later to accommodate commissioning staff

It was pleasant to be working again after over a year’s unemployment in France, to feel that I was engaged once again on a stimulating project. It was also nice to be ‘permanently’ back in England after an absence of over 20 years. We were in an area with which we were familiar; I had worked on Weaver Viaduct in the late 1960’s and we had spent much time in attractive Chester, close also to Deeside.

The main difference was that at time we then had four children[4] and had lived in our own house at Frodsham; now we were on our own, all five children grown up, and were looking for furnished rented accommodation.

Cubby visited estate agents, read the local papers and set about this task. Fortunately there seemed to be a fair number of furnished properties to rent – somewhat surprising - this is not always the case in England and Wales. After hectic days of viewing properties, Cubby relaxed in the hotel’s indoor pool. In the evenings we ate out of the hotel as their good meals were fairly expensive at about £20 each. We found that Indian, Chinese and Italian restaurants provided good value comparing to basic greasy spoon ‘transport’ cafes where ‘breakfast all day’ seemed to be the menu choice. Later when more settled, we found a delightful unpretentious restaurant run by young French people in Chester - without fancy prices – there was no white linen – just bare boarded tables and old French advertising posters on the walls. Occasionally we enjoyed battered fried cod with chips wrapped in white ‘newspaper’[5] – a good buy in England, but I did not sprinkle vinegar - it spoilt the taste.

After I had established effective postal and telephone[6] communications, independent of the hotel, we found a ‘bed and breakfast’[7] across the Dee river east of Chester’s timbered Tudor shopping ‘rows’. We settled for some weeks in a sunny room with en-suite bathroom. Our host and hostess (a retired professional couple) willingly gave us poached eggs and fresh fruit rather than enormous cholesterol fried bacon, egg, suasage and baked bean breakfasts. Cubby could walk into town over a pedestrian suspension bridge crossing the tranquil Dee river with it’s pleasure craft, oarsmen, swans and ducks, a symbol of domesticity - we were well content despite the occasional rain showers.

|

|

Our rented terraced house at Handbridge, Chester |

After several inspections, she found a delightful small house in Handbridge – not far from our B&B. It was on a Cul-de-sac, Pyecroft Road, in what had once been a working class area, but had now been ‘yuppi-fied’. A modern equipped kitchen at the rear, and inside plumbed bathroom had been added (offshot) to what had been a typical workman’s ‘two up, two down’ roomed terrace house. We felt we could live with both the furniture and the décor – Sanderson’s wallpaper and brass bath taps. We asked the owner to remove the TV sets from both bedrooms – one in the lounge was more than sufficient to watch Wimbledon where Jeremy Bates reached the last 16 players. In front we had a minute garden and at the rear a paved yard where pot plants could be placed – Cubby’s green fingers could be used. We paid £425 a month - the cost of services and council tax was to our own account. Commuting by car to work was easy, my route and timing avoided rush hour traffic.

|

|

Cubby's picture of the house behind ours seen from our back bedroom window |

ABB let the main civil works to the same contractor doing the preliminary works preparations. On site I continued regular weekly meetings[8] with their staff looking as far as possible in the future to prompt pre-planning, preparations and procurement for their works. Younger site engineers, often through lack of previous experience, tended to concentrate only on the jobs immediately at hand and would complete them before thinking about the next stages – this could cause delays through lack of foresight. I minuted the meeting and issued them within days and monitored progress at the next meeting. The contractor also tabled his schedule for the next few weeks construction. Minutes could be ‘two-edged’ – they could also record possible information / design delays which might hinder progress – some managers thus preferred to do everything verbally to avoid records.

About six months after starting the Site Manager, a Scotsman, and the Erection Manager a Dutchman joined the project. Effectively I now reported to the Erection manager on site but at the same time was Engineer Representative for the Engineer co-ordinating the design based in Newcastle - it was easy to get on with all of them and with the Client National Power’s on site civil representative. By this time I had some civil works assistants. Two had worked on ABB’s project at Killingholme across the country not far from Grimsby, and another was seconded from the company doing the civil design. They helped control and monitor the civil contractor’s activities.

ABB’s scheduling engineers also established on site. They, after discussion with production engineers in the various disciplines (civil, mechanical, electrical etc) ‘typed’ network logic schedules on their desktop computers and then printed them directly. On the Weaver Viaduct 20 years earlier I had manually scheduled activities and then taken them over 200 miles to a mainframe computer centre in Glasgow. Cards had then punched to feed data into the computer before it would ‘draw’ and calculate the schedule. This new system was a great improvement.

Another significant change taking place in the past 20 years was working attitudes and practises. On Weaver Viaduct the Labour Union representatives (usually from Liverpool) had been all powerful. They cracked the whip by strikes (or the threat of them), making construction projects management accept directly employed labour’s usually excessive wage and bonus demands. They had also blocked the employment of any ‘labour only subcontractors’ who would not accept Union dictates. Labour induced delays could make contractors overrun contractual ‘target dates’, often facing financial penalties imposed by the Client. Now all this had changed – Prime Minister Thatcher had broken the unreasonable powers of many Unions. There was now virtually no threat of industrial action and many small subcontractors were employed rather than direct labour.

Other significant changes had arisen in the past 20 years to Quality (and Safety) management. The concept of Quality Assurance was now being enforced in the construction industry making contractors plan, implement and check their works in a structured and verifiable way. Good construction engineers had previously probably done most of this anyway, but could slip up on occasion and some probably did not have the vision and experience. Without a thought out and recorded system, vital checks and records could be missed, leading to uncertainty of the quality. The downside to this was that often overlong and sometimes irrelevant procedures were written merely to fulfil perceived Standard requirements. The earlier system (as at Weaver Viaduct) where a Consulting Engineer had checked the implementation of the design in total was no longer common. The contractor doing the work was now usually responsible for his own implementation and checking. At Deeside we wrote this concept into our Civil Works subcontract and generally only did surveillance checks on the subcontractor’s works to ensure this.

Cubby with time on her hands during the week started doing voluntary work within the community. She helped at a day centre in Chester for adults who could not fully cope with everyday life. She ended up producing a midday meal for up to 40 people once a week and instructed a few of the women in sewing and other handcrafts. She also attended a course on teaching literacy. She became a voluntary teacher of foreign immigrants[9] English and locals who had somehow never learnt to read and write at school. She joined a local art club and started painting in watercolours – some of which she placed on an annual exhibition and sold.

At night Chester seemed to be a well-behaved middle class town and we did not hesitate to go out. One night, when we were queuing for cinema tickets in an attractive square, our perceptions changed. A fight started between some youngsters outside a public house and one lad falling on the ground was kicked viciously several times by another, the public seemed to avert their gaze disowning these yobbos.

On Friday afternoons many of our staff left to travel home to see their families all over Britain and returned on Monday mornings. As I was locally based, I worked 3 out of 4 Saturdays but had Sundays off. We frequently drove into the Welsh countryside. The A55 expressway, built since our previous stay, now gave speedy access into Snowdonia and other parts where we walked in inspiring countryside. We no longer had to travel tediously on the flat north coast road with its regiments of caravan parks and seaside towns full of uninspired houses and bungalows. Further along, Llandudno, with its Victorian terraces, was architecturally more attractive.

We visited Andrea (then working as a freelance carpenter[10]) and Christopher (working as a psychiatric nurse) in Sheffield or they came to see us. After a while I found it was pleasanter to drive over the moors via Buxton through the Peak National Park rather than heading towards Manchester on the M56 (crossing the Weaver Viaduct[11] – my earlier project). For the first time in about 30 years, we qualified by nationality and residence to vote in an election, not a General Election, only for local city councillors.

I persuaded Cubby to climb Snowdonia following the Miners track. She coped well with the ascent but found the descent less easy.[12] Later she declined to do it a second time and I then went up a more interesting route with Andrea. This started with a series of easy short rock sections. We also enjoyed walking in the hills above Conway. I started playing squash again with colleagues at the site, enjoying it, but finding that it seemed to make one of my hips pain afterwards.

Inevitably the civil works fell behind. Our management started exerting pressure on the civil and building contractor to catch up in an endeavour to meet plant commissioning target dates. The main reason for the delay was that two separate subcontracts had been let – one for civil concrete and building work and one for the Powerhouse structural steel framework. The steel framework delivery and erection was late and delayed substantial parts of following civil works. Further, illogically, steel stanchions also extended below the ground floor level (rather than anchoring them at ground level as had been done on all of my earlier projects). So even ground floor works could not be completed until steel was erected.

This created an atmosphere of crisis and optimistic promises were extracted at special meetings from the civil contractor by ABB’s visiting managers to finish and hand-over certain areas for mechanical and electrical erection works by certain dates. Some targets involved working during Christmas and new years holidays. Invariable such arbitrary dates were not met - labour was disinclined to sacrifice their holidays. Probably the civil contractor put forward claims for delays and acceleration - they had a large number of Quantity Surveyors on site - more QSs than Engineers, always an ominous sign.

|

|

|

|

|

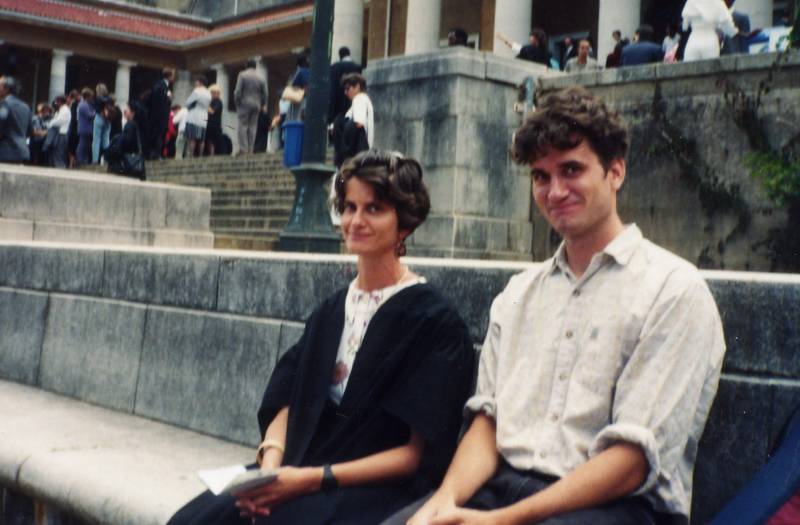

Cubby strolling with Christopher, Ruth, and Andrea along the River Dee near Chester. Ruth and me alongside Ullswater in the Lakes en route to Scotland on holiday. Christopher and I, also on holiday, survey Ireland. |

|

During holidays on this project, we had toured the west of Scotland with my sister Ruth over from South Africa. We walked on Skye to sea cliffs and saw the pillars called Macloed’s ‘maidens’ rising from the sea – Cubby’s floppy sun hat, bought in China, blew off and fluttered down to the sea below – we stepped back cautiously from the windy edge. Later, we crossed by ferry[13] with Christopher from Holyhead to Eire and drove down to the South East - the Dingle peninsula – Christopher and I dipped in the icy cold water and retreated immediately – Cubby impervious to the cold swam for some time.

|

|

|

Ed, Ben, Nicky and Ruth in the courtyard of Nicky and Ed's home in BoKaap. Karen (with Ben in front of Jamieson Hall) in her graduation gown in 1993 after obtaining her teachers diploma. |

|

We also visited Cape Town in 1994 seeing our three children there – Nicky working in farming ecology, Karen teaching and doing some freelance art work, and Ben at the University of Cape Town studying philosophy. We divided our stay between my sister Ruth in Mowbray and Nicky and Ed in Bo Kaap above the city. Despite ongoing changes from the Apartheid state and the assassination of Chris Hani (African leader of the South African Communist Party, returned from Exile the previous year) all seemed reasonably peaceful in the Cape.

We visited Cubby’s sister Tippe and her husband now living in Fish Hook and even persuaded Tippe to take her first sea bathe since moving there years earlier – Fish Hook had been one of our favourite beaches as children. My other sister Judy also flew down from Johannesburg to see us. Daughter Karen took part in the 104km round Peninsula charity cycle race and we waited in vain at Camps Bay for her to pass. She had dropped out just over halfway before Chapman’s Peak Drive[14] leading to Hout Bay.

With Ben I climbed up Table Mountain following a route looking directly above the town mainly in Africa Ravine. We turned right under the cable way station and traversed below the massive rock faces and ascended behind the café at the top of the plateaux. I welcomed the chilled drink we then took, I was no longer used to the heat and the sun. Ben, in an earlier role as a science student’s representative, had previously accompanied visiting David Attenborough, the naturalist, on a similar trip up the mountain.

I also attended my Rondebosch school class 40th year anniversary - my schoolmates now visibly older and greyer than at the 25th reunion were now less easy to recognise. My old rugby coach Tinkie Heyns gave a diplomatic dinner speech advising us to accept the new political realities both in the country and school – it was now a multi-racial society. Another teacher Charlie Halleck well in his eighties seemed to be enthusiastically knowledgeable about the ‘five nations’ rugby games in Europe.

The South African currency the Rand had however devalued by a third against the UK pound since we had left South Africa for the second time in 1980. Our Wynberg house was now apparently valued at R380.000, rather more than the R46.000 for which we had sold it 14 years earlier.

Back on site my 2year contract was almost completed. The project had been interesting and on the whole enjoyable despite some friction within our organisation at the end. Civil works had delayed M&E erection works and I had undiplomatically put in writing my criticisms of civil design - the major delaying factor[15] in my view. However, the level headed Dutch Erection Manager must have supported me when the Swiss Project Manager for a future project in Malaysia visited Deeside and spoke to me. ABB offered me a position in Malaysia managing the civil works - I was happy to accept.

Towards the end of our stay in Chester a bizarre situation arose. The English tenant in our Paris apartment telephoned us in an agitated state – he had lost his job. A one time colleague from Spie Batignolles, a Northern Irish Protestant, who I had met in Paris about 10 years earlier after my first Malaysian project, had introduced us to our tenant – they were both working for the same legal firm in Paris which dealt with construction problems.

Apparently my colleague, unbeknown to me, had later started his own legal company and persuaded our tenant to join him. Our aggrieved tenant informed us that my colleague had portrayed himself as being both a professionally qualified civil engineer and a lawyer. It now transpired that he had apparently misrepresented himself as a professional lawyer and his business had collapsed once this was uncovered. So a talented and competent colleague (fluent in both Italian and French and a very good squash player), and a plausible sympathetic friend when I had lost my job in France, now turned out to have been economical with the truth. I now pondered whether he really had been a fully qualified professional engineer but I had attended a local Institution of Civil Engineering meeting with him?

We never received the last months rent on our apartment.

[1] Wales called Cyrmu in the Welsh language

[2] Combined cycle gas turbine plant gave rapid start up and flexible electric supplies compared to ageing coal and nuclear plants. Combusting Gas drove gas turbines, then as exhaust heated water producing steam driving further steam turbines.

[3] NEI – Northern Electrical Industries – later during the project ABB split from NEI and worked under their own name.

[4] our fifth child was born later in Guernsey – my next project after Weaver Viaduct – see separate chapter

[5] apparently the use of actual newspaper with print was no longer permitted

[6] the ‘mobile phone’ revolution had not yet generally started in England – Hong Kong and other countries seemed in advance

[7] Chester with many tourists housed most in B&B rather than hotels - a quintessential British institution - now copied in other countries.

[8] Today actions required would probably be best recorded on a ‘continuous’ updated ‘data base’ rather than as separate weekly minutes

[9] I do not recall any paranoia about asylum seekers - this later became common in Britain after the millennium – possibly the ‘problem’ was less acute or people had drifted to the right on social issues since then.

[10] She had trained in London, enjoyed the work but found male carpenters rather chauvinistic

[11] on one occasion I walked under the viaduct and found after more than 20 years the concrete faces were in pristine condition

[12] She had had problems with her knees – one had dislocated some years earlier.

[13] the ferry, an Australian built catamaran, gave a fast and steady ride.

[14] Some years later this magnificent drive above the sea closed indefinitely because of rock falls.

[15] Civil design should ensure speedy construction especially where there are tight deadlines – as Turnkey contractors our designers should have ensured this.

index memoir -

homepage - contact me at