index memoir - homepage - contact me at

When I was packing up to leave the Nuclear Power Plant construction site at Daya Bay in China, Spie Batignolles offered me a job as Site Manager on a small project in Lesotho building a housing colony for the Lesotho Highlands Water Authority. This had to be completed in advance of the start of construction of the new Katse Dam. House building was not the large-scale civil engineering work of my past experience, but we would pass through South Africa to reach Lesotho and could see two of our children - a considerable attraction. Our daughter Nicky was studying for a higher degree in botany at the University of Cape Town, and Karen, our second daughter, was at Pietermaritzburg University.

I accepted the assignment. Later as a bonus we would also see our son Benjamin, who had completed his schooling in Denmark, become bored with a gap-year after six months and with the help of Nicky enrolled to study at the University of Cape Town starting in February 1990.

Cubby and I flew directly to Johannesburg from Hong Kong and I reported to the company’s local manager. Because of possible sanctions against foreign companies working in Apartheid South Africa, Spie Batignolles did not work under their own name but ran a local company Comiat. They could, however, use their own name in Lesotho.

I did not know Johannesburg well, but it was apparent that although Apartheid was not yet dead, the city was becoming more Africanised. Whites were already retreating to their plush suburbs and shopping centres while African traders were now crowding the city’s sidewalks. The laws segregating living areas had not yet been lifted, but some ‘white’ areas were now experiencing a de facto integration. We visited the private school Cubby had attended and saw a few African and Indian children were being admitted – only very wealthy parents, which not many blacks were, could afford to pay the school fees.

|

|

|

Cubby with my sister Judy and her husband Nigel |

My sister Judy and her family had been living in Johannesburg for many years and we visited them at their suburban home. Her husband Nigel ran a small stall at the huge Carlton Centre hotel selling and buying amongst other items coins, one of his interests.

We drove in a hired car on holiday to the Kruger Park and other areas in the eastern Transvaal, my first visit. Cubby had visited there several times as a child roughly 40 years earlier and had memories of primitive camps, fenced to keep out animals - especially Hyenas and Lions - and of the smell of braaing (barbecuing) meat in the evenings. Some dirt roads had now been surfaced with tarmac. Despite more cars, we saw countless antelopes usually camouflaged motionless in the scrub. Giraffes grazed delicately above tall scrub or crossed roads in slow loping motion. We slept outside the park in hotels which provided good buffet meals, I especially enjoyed eating dark yellow roasted pumpkin again – something seldom available out east or in Europe.

|

|

|

|

Blyde River Canyon in the then north eastern Transvaal |

|

We then drove through Swaziland - I had worked there in Colonial times as an assistant surveyor during one university holiday in the late nineteen fifties. Passing hot springs, I recalled spending a New Years Eve bathing with the daughter of a local Danish farmer. Later we saw refugee camps, stretching for miles, housing people displaced by civil war[1] in Mozambique.

|

|

|

|

Game park in Kwazulu-Natal |

|

In Pietermaritzburg, Natal we met Karen who was in the midst of separating from her husband. She had left Nursing and was now taking a Degree in Art and Geography. At this time, with Apartheid crumbling, much black on black violence between Zulu ANC and Inkatha factions occurred. There had been several assassinations – some were ANC personalities who Karen knew. We hoped that Karen would relocate to Cape Town as soon as feasible.

|

|

|

|

Visit with Karen to the Drakensberg not far from Pietrmaritzberg |

|

In Durban, my first visit to this city, we visited my uncle Geoff, now in his late eighties, the younger brother of my father. He was living in an old age home and after a recent illness had been forced to give up jogging - his hobby for decades. He could not place me. I was now grey-haired – perhaps I was his deceased brother mysteriously returned from exile in Cape Town? Cubby, who he had first met as a teenager, visiting Natal with her parents from the Cape prior to us emigrating abroad, he immediately recognised and talked animatedly to her – she was not grey-haired and little changed in appearance since they had last met in Cape Town in the nineteen seventies.

|

|

|

Cubby's sister Tippe with her husband Johnnie |

Tippe, Cubby’s half sister, and her third husband Johnny were now also in Durban. They had retreated to South Africa like many white Rhodesians just before Rhodesia became independent Zimbabwe in April 1980. Tippe had previously worked successfully as a nurse, window dresser, interior decorator, newspaper columnist, and property salesman and was now working at home to make ends meet sewing dresses for affluent white teenage girls to wear to end of school parties.

Few, if any, passenger trains now went to Cape Town from Durban, so Cubby flew down to Cape Town to visit Nicky and her partner Ed February while I had to start work in Lesotho. I drove round the north of the Drakensberg, then southward into the Free State under intense blue and white-clouded skies passing rugged chopped off hills. As a student I had worked in the Free State on farms near the small town of Senekal with a friend Corder harvesting wheat during one university summer holiday. Most of the Basotho black labour helping with the combined harvesting machine spoke Afrikaans and tested my limited school knowledge of this language at that time.

After immigration formalities, I crossed into Lesotho over the Caledon River. Cars took turns bumping over the sleepers of a single lane combined railroad bridge before driving on to nearby capital city Maseru.

Maseru, built on hills, seemed a rather scruffy town with a few wide tarred roads in the centre but resorting to dust in the suburbs and in front of our offices. Farmlands and little shacks sprawled on all available gradual slopes. Many half built houses optimistically started and possibly unlikely to be completed lay on the outskirts of the town. At this time it was dry but when the rains came the parched soil would be transformed to lush green. I stayed for some weeks in a hotel before fetching Cubby at Bloemfontein Airport, named as was then the custom after earlier Afrikaner Prime Minister, J M B Hertzog.

I would work in Maseru for some months planning, organising and expediting supplies while our advance team was establishing temporary housing and offices in the high mountains. When checking the Consultants drawings, I found many omissions of details - we brought them to their attention and asked them to supply these.

We moved into a small compound in Maseru called Kokobela Village - a mixture of stone built rondavels and square rooms either thatched or tiled. A rough track bumped up a few meters from our front door facing south away from the sun. Not much sun got into the small back (north) windows either so it was rather chilly home but became warmer in summer. Out of our bedroom and kitchen windows facing north we saw a range of mountains, some flat, but others resembled the conical Basotho hat that was also the national emblem. Around our village, yellow roses and purple wisteria clambered over split pole fences. Little gardens of ‘forget-me-nots’, snap dragons sweet peas, geraniums and daffodils also gave an English country garden effect, if you ignored nearby enormous Aloes and blue gum trees. Spring was on its way and deciduous trees were still bare, but weeping willows, poplars and birches were now peeping with young green leaves.

Cubby was pleased to be in a country where people smiled easily, indeed generally with perfect white gleaming teeth. She had found Mainland Chinese and Hong Kong people somewhat dour, although personally I thought they behaved little differently from many Europeans but were less aggressive. She employed a local woman to help in the cottage for the next two months and to teach her Sotho.

As was her habit on arrival at a new home, she immediately started gardening. But there was infrequent rain – it was a period of drought. She constantly lugged buckets of water to pour over plants. Occasional intense rain, seldom lasting even 10 minutes, skidded off the baked soil sinking in a mere 3 to 4 cm. Thanks to her watering the garden was most profuse, we ate spinach every second day and lettuces also throve. Tomatoes flowered and started making golf ball green fruit. Aubergines, pepper plants and courgettes also flowered.

Cubby attended the local Anglican Church, a cathedral built in stone with a homely English look. Inside it was like a Maltese cross with the altar in the middle. Natural light revealed white painted roof trusses cris -crossing above. There was no organ, not even a piano, someone would start each hymn and voices would join in with different descants and harmonising till the whole place boomed with glorious sound. Although Christianity was now strongly represented in Lesotho by both Anglican and Catholic denominations, it had first been brought to Lesotho in 1833 by the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society.

We sent for our household belongings, which had been stored in Cape Town for the past 9 years since we left with false optimism to work in Iraq. We would use these to furnish our house up at Katse. But time had moved on - our children’s precious books and toys were now outgrown - and we sadly gave most of these and a number of tents from family camping holidays to local people.

We visited nearby Ladybrand in the Orange Free State hoping that shopping would be more diverse, but were disappointed - the selection of food in the supermarket was no better than in Maseru. We found several drankwinkels (stores selling bottled alcohol) in this dorp of three or four crossing streets. A puritanical modernistic Afrikaner church with obligatory tall spire disapprovingly dominated the town. Cubby also visited Bloemfontein, a pleasant town, and tried to recall her school Afrikaans as it was the dominant language spoken. She was amazed at the height of many of the white women, many close to 6 foot tall and felt quite small. Out East at 5ft 5inches she was tall and in Lesotho average height. We also visited Golden Gate in the Free State north of Lesotho where Cubby had spent several childhood holidays with her family on a farm.

|

|

|

Visit to golden Gate in the Free State north of Lesotho |

With the appointment of F W de Klerk as South African President in early 1989 after P W Botha had suffered a stroke, ‘Petty Apartheid’ had been somewhat relaxed. In some of the ‘Steak Houses’ a few blacks were now permitted to eat alongside whites - otherwise not much else seemed to have changed in South Africa since our second departure in 1980.

Lesotho had gained independence after British colonial rule in 1966 and was hostile to its encircling neighbour, white ruled Apartheid South Africa. They had given sanctuary to ANC members and other opponents of the S A regime. Later, in retaliation South Africa virtually blockaded the borders stopping the movement of goods and people, effectively strangling Lesotho’s economy. The wages of Lesotho miners working on gold mines on the Witwatersrand was a significant contributor to the country’s economy.

In 1986 Chief Jonathan and his government were overthrown by a military coup. South Africa then finally negotiated the implementation of the Highlands scheme. A series of large dams and water conduits bored through the mountains would supply water to the industrial areas of South Africa furthering their industrial development. Apparently some hydro-electric power would be produced for consumption in Lesotho itself but supply of electricity to South Africa, which had an abundance of coal fired power stations, was not envisaged. Our project was a very small part of this giant scheme planned and managed by the Lesotho Highlands Water Authority.

Early in the mornings before going to work Cubby and I went for strenuous walks around our neighbourhood in an endeavour to keep fit. During one of these, we passed an army officer out jogging who, apparently fearing assassination, disturbingly carried a gun in his hand.

Because of Lesotho’s independence and stance against South Africa, many countries in the world had an embassy or consulate in Maseru - especially communist countries not permitted representation in South Africa, or other countries withdrawing their embassies or consulates from South Africa in protest against Apartheid. There were disproportionately large modern complexes for Russians and both mainland communist China and offshore Chinese Taiwan considering Lesotho’s small size. The latter two ensured that there were Chinese restaurants where, irrespective of political persuasion, one could enjoy good food. The Americans in the midst of the ‘cold war’ in Africa also had an impressive new embassy. Many ‘relief agencies’ were still ‘pouring’ in money to benefit the impoverished people of the ‘Kingdom in the Sky’. It was not clear how much of this ‘aid’ actually reached Lesotho - a high percentage of aid is usually spent in the donor countries themselves and supporting their aid workers on the spot in relative luxury. Also of the aid actually reaching Lesotho, how much stuck to the palms of politicians or bureaucrats?

With Lesotho military regime now cuddling up to South Africa the Danish Volunteer corps appeared to be in disfavour and seemed to be returning home. We bought a second hand 4X4 bakkie (pickup) intended mainly for Cubby’s use from a departing Dane. The new Lesotho regime apparently now thought it got enough aid from S A not to require it from S A’s perceived enemies. We wondered whether this animosity extended to the telephone (calls were routed through South Africa) as Cubby only got the engaged tone when trying to contact her relations in Denmark. Danes apparently could only get a 48 hour transit visa through SA which took 6 weeks to get. In turn it was very difficult for South Africans to get Visas to visit Denmark.

I took several trips to monitor progress on the establishment of the site. We sometimes drove in 4 wheel drive bakkies eastwards towards Thaba Tseka, the nearest town about an hour from the site, up a series of precipitous dirt road mountain passes with frighteningly but accurately descriptive names – boesman’s pas, god help me pass. The journey could take over 5 hours. We saw several rusting wrecks tumbled down mountain slopes. The sides of even remote roads were covered with empty beer cans - alcohol may well have contributed to accidents.

A new surfaced road coming from the north was being constructed to Katse. This would make the transport of people and construction materials for the dams and tunnels more feasible in perhaps 6 months time.

Sometimes we flew up to Katse in small Cessna single prop planes, owned and piloted by South Africans who flew over daily from Natal to pick up passengers from Maseru. Taking off and landing from the longish surfaced runway in Maseru was no problem but in the mountains with rough gravelled airstrips it was more hazardous and sudden poor weather conditions could delay or cancel flights.

Cubby accompanied me on a flight to the site to see the progress on building our future prefabricated home. We rose to 10500 feet over mountains and reached a maximum speed of 140mph. The earth below from our birds-eye view looked like a toy model. The hills were striped with fields of green crops of varying shades - not terraced but sloping - some very steeply. Everything seemed idyllic - we could not see any scruffy squalor around little encampments of thatched rondavels with square or round dry stone walled kraals for cattle. Some of the villages seemed very isolated without tracks zig-zagging to them. Riverbeds twisted back and forth like swaggering snakes. Some tributaries formed quite large rivers and these flashed white where they gushed over shallow rocks. Mountains also glistened with water in patches - there appeared to be plenty of water – the problem was to get it up to where the crops are growing.

|

|

|

|

View from a Cessna plane of a winding river below the mountains. I wait at the end of the runway with Geoff Metcalfe, subcontractor for prefabricated housing for a plane, hopefully livestock would be clear of the strip when the plane landed. |

|

|

|

|

|

Traditional huts and villages - probably in the lowlands where trees can grow. |

|

We twisted sideways between ridges to get to our airstrip near Katse - almost as though the plane’s wings were too wide to pass between them. The airstrip undulated a few hundred meters through a village - the pilot said he had fortunately seldom encountered cows and sheep. As the runway was short and bumpy often only 3 or 4 passengers could be accommodated depending on amount of baggage and whether the pilot was an optimist or pessimist. After becoming airborne the plane sank down into a canyon then struggled to rise and turn missing a nearby mountain peak. When in the mountains the weather could deteriorate and we would have to wait for the plane to return later, or on some occasions we would loan a vehicle from the site and return by road.

We drove the fifteen minutes from the airstrip to our housing compound and office areas on a treeless, exposed plain above the deep river valleys but with a mountain ridge behind. The valleys below would be flooded with water once the Katse Arch Dam[2] was built. We would draw our tea coloured drinking water from a small stream running from the mountains behind us also serving an existing Basotho village. The villagers descended miles down into the Katse riverbed with donkeys to fetch wood for use as fuel from brush and trees growing within the sheltered valleys and not on the upper plains. Some Aid Workers, based in Maseru, were concerned that villagers would be deprived of this source of fuel and were perturbed whether any alleviating measures would be provided once the dams were built. The only other natural limited supply of fuel was dried dung from cattle herds sometimes collected by Cubby as fertiliser for her vegetable patches.

The building of our racially integrated housing camp for staff and tradesmen and barracks for local Basotho labour was proceeding. Our bungalow, sited with a view down a valley and hills beyond, would be ready for occupation in the new year. Offices and stores and the plant for crushing and grading local basaltic stone for making concrete was also being erected.

|

|

|

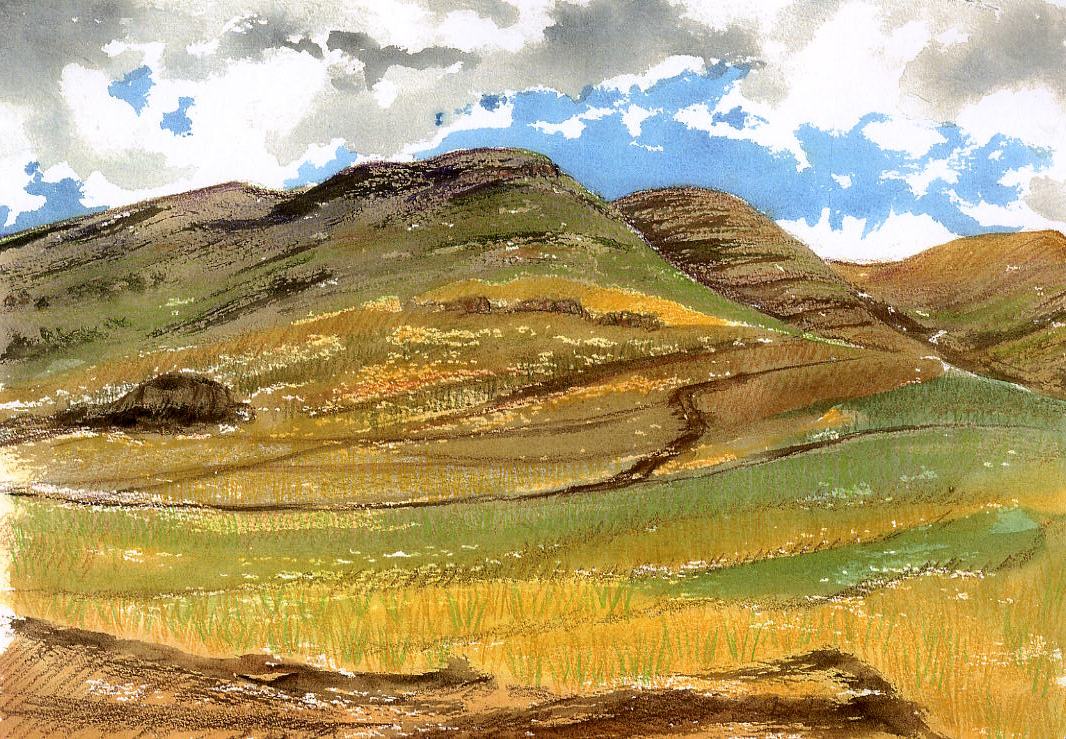

Cubby's sketches of the mountains near our house at Katse |

|

The Basotho labour was restless. They were unhappy with the payment rates set by their own government and on which contractors had based their successful tenders. Although we paid above the minimum rates, unofficial ‘union leaders’ who had gained experience in South Africa working on mines and industry, tried to intimidate the staff working on infrastructure projects to raise payment levels still further. It was rumoured that some Basotho politicians, deposed by the military government, were unhappy with the ‘water’ deal with South Africa. These wage disputes were possibly a political trial of strength.

On occasion labour stopped work and picketed and invaded our offices and compound. The nearest police post was an hour away in Thaba Tseka. Even if we got a message to them, they either did not come, (no transport?) or would arrive much too late. Probably they did not wish to confront striking labour. Meetings were held with the local labour on site and initial compromises reached, but it seemed as if they would continue to exert pressure for increased rates of pay. Radio communications were independently set up by the various contractors to talk to their offices in Maseru, but the equipment and terrain was such that this was unreliable – staff trips back and forth became necessary in endeavours to resolve labour problem. Despite this the area was beautiful and we looked forward to moving to the site in the new year.

|

|

|

|

Christmas in Cape Town at Ruth's house with Nicky and Ed, and Karen. |

Karen with Ben near Bloubergstrand framed by Devils Peak, Table Mountain, Twelve Apostles and Lions Rump and Head. |

Just before flying down to Cape Town for Christmas, I had an operation in Bloemfontein to remove lumps under my armpit found later to be benign. We stayed with my sister Ruth in Mowbray and saw Nick and Ed now living in Bo Kaap - on the slopes Signal Hill just above the City. Bo Kaap[3] had remained a Coloured suburb. Ed had inherited this home originally owned by his aunt a midwife. Karen, who was also visiting from Pietermaritzburg, stayed with them. Ed, who normally climbed severely difficult rock, took Karen and me for a rock scramble up Wood Buttress on the western side of Table Mountain. I recalled climbing it about 36 years earlier with a Rondebosch Boy’s High School group lead by a teacher ‘Doc’ Watson who had since died in a rock climbing accident on the same mountain.

In the New Year back in Maseru Coloured tradesmen recruited from the Western Cape arrived and we moved up the mountains off to the Katse site in a convoy of 4X4 bakkies and lorries knowing that we would be welcomed by a labour strike. Much of our furnishings for our house had been sent up in advance in the previous month with routine transport, but we carried the balance and food for the next weeks - there were no supermarkets in the mountains only a few trading stores with tinned supplies – beer seemingly being one important item. Shortly after moving into our house the Chief of the local area visited us, blanketed on horseback. At tea, our first guest, commiserated with us over the current labour strike and unrest – blaming it on ex-miners.

As it was now summer and autumn would arrive early in the mountains, Cubby resolutely started a new vegetable garden hiring a labourer for 5 days to dig and form beds. 5 days was the time limit for casual labour. She started planting and watering first with buckets then later with a hose. Wild rats started gnawing off the tops of rapidly emerging plants, fortunately re-shooting when the rats had been poisoned. In due course carrots, aubergines and courgettes were harvested and eaten.

Flocks of Storks arrived from Europe, an auspicious omen we hoped – forlornly as it turned out.

Cubby also took on a servant – not a genuine local from a nearby village as most labour wishing to work on the project seemed to come from other more distant parts of Lesotho, and few locals seemed available.

We had a very mixed bunch of staff and tradesmen including:

- a Quantity Surveyor from Botswana, almost San, in appearance.

- a Basotho woman Quantity Surveyor who had been trained in Russia

- a Basotho Civil Engineer who had studied for 7 years in Rumania for his MSc.

- two Filipino Engineers who had worked for Spie elsewhere in the world

- a chief mechanic from Kenya

- a Coloured Foreman, member of the ANC and a political refugee from South Africa

- Coloured tradesmen from the Cape

- Both South African and foreign whites – mainly foremen.

The field works were ably lead on site by my deputy, the construction manager, experienced in Lesotho conditions and with dual South African and Irish nationality. Later I took on a locally resident European expatriate as, recommended by our manager in Maseru, to lead one section of the work as we were behind schedule. He proved not to be a team player and was disliked and resented by the rest of the site staff – an unpleasant and unproductive situation - I had made a poor decision.

Cubby spent much of the 11th February 1990 glued to the BBC’s World Service Africa radio transmissions of Nelson Mandela’s release from the Victor Verster Prison near Paarl[4], a pretty country town amidst grapevines, not far from Cape Town. His delayed arrival and speech to thousands gathered in front of the Cape Town City Hall was also relayed. We were pleased that the days of Apartheid, introduced by the Afrikaner’s National Party on their election in 1948, were now finally doomed. I remembered, as a 10 year old, being told by my gloomy parents that a stupid and iniquitous racial policy it was. We now, 42 years later, hoped that the inevitable transition to Black rule would be peaceful and that their governing would be mature and fair.

Our 70year old Camp Administrator had found the labour situation irksome and decided to finally retire and return to South Africa. We held a farewell braaivleis in the riverbed below our site, our bakkies lurched and bucked down the steep tracks carved through rocky outcrops. It seemed another world here - peaceful trees, pools of water – all later be covered by the Katse dam. We turned hunks of meat sizzling on grids above glowing charcoal in cut down oil drums and drank Castle beer straight from the can.

The wife of the Consultant’s architect on site started a small magazine ‘The Katse Chronicle’ recording the more social aspects of life on the project, and the comings and goings of visitors and staff. Cubby was roped in to design the cover page.

On the permanent housing site lying on a hilly outcrop, we excavated down to the shallow bedrock for house foundations. We blasted trenches, an expensive business, to lay gradually sloping foul sewers. To stop debris from flying about and damaging the Clients nearby temporary building for housing his staff, we covered areas which had been drilled and charged with blast mats – none the less in time the building was perforated with holes which were progressively repaired.

We crushed solid black basaltic rock as aggregate for concrete. Small chippings, a by-product of this operation, were mixed with sand, imported at great expense (as it was not available in the local area), and cement to produce a dry lean concrete from which we then pressed bricks for house building. We started using these bricks up to ground floor level.

At this point the Client intervened, he over ruled the Consultants and said that bricks made with basaltic aggregate must not be used in future. Basaltic aggregate used in concrete had shrinkage properties, indeed some high concrete bridge piers on the new road towards Katse had apparently shortened about 20cm. We agreed that basaltic concrete shrunk, but argued in vain supported by outside experts, that as bricks were not massive concrete structures and only 9 inches long shrinkage effects in brickwork would be negligible and accommodated at joints. Fortunately those bricks already placed were accepted and demolition was avoided.

Over the Easter holidays we began importing burnt clay bricks at great expense up the mountains.

|

|

|

|

Red hot pokers and aloes photographed from the challenging mountain passes. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mountainous Lesotho is renown for its horsemen |

|

As we worked almost all Saturdays and Sundays, every three or four weeks we took a break driving to Maseru both to replenish food supplies and to consult with the local manager. The drive was always spectacular. The countryside was always changing. Early on we had seen huge aloes up to 30foot high with yellow tufts turning pink before going brown and withering. Later we saw a myriad of red-hot pokers, actually both red and yellow, with pale greyish green leaves. There were also hundreds of other purple, white and yellow wild flowers more sparsely dotted around including beautiful pink-orange gladiola. After rain had fallen for some days, little streams appeared and gushed over cascades and falls. The mountainsides would glisten with water on bare rock. Once, for almost an hour, we passed large groups of blanketed horsemen returning from some gathering in the country. Some of them wore the traditional Basotho hats.

In Maseru we discussed ongoing labour difficulties – strikes and demands for higher payment rates for general labour and demands for increased payments by unproductive local brickwork subcontractors. They were using political connections to resist the importation of skilled bricklayers from South Africa.

One long weekend break we drove north through Lesotho around to Pietermaritzburg to see Karen. On our return we stayed near the reddish yellow Golden Gate cliffs and caves where Cubby as a child had spent holidays with her family on nearby Sunny Side farm when they were living in Johannesburg.

Over Easter we went down to Cape Town again, as did many of our staff, and saw Benjamin who had now started at the University of Cape Town. We took a one day walking trip in the Grootwinterhoek, the blue purplish distant mountains I had seen across the wide Picketberg valley when I had worked there as a student during a vacation on a cement plant.

Back on site the labour force gave notice of their intention to go on strike again. At about the same time Spie’s Johannesburg Manager visited the site and after talking to the Resident Engineer informed me that Spie would be removing me from the project. He said my letters, requesting details, and pointing out the lateness of their drawing supply, had not been happily received by the Client. This seemed a rather weak excuse. Spie possibly felt that a hard line on information supply with potential delay claims on this small project may prejudice acceptance of their bid for the large Katse Dam itself, and I was removed as a consequence. The local Maseru manager and my site construction manager also departed within a few months.

In the event the Katse dam construction was later awarded to another contractor. Spie[5], as part of a consortium, were sometime later awarded a contract for the tunnelling of water aqueducts starting from this dam.

We went down to Maseru where I spent a month tying up loose ends and ironically started drafting a delay and cost claim.

Cubby’s hearing in one ear had been getting poorer, probably a hereditary defect as her father’s hearing was also poor, and she went to see a specialist in Bloemfontein who later operated to rebuild the small hammer, anvil, and stirrup bones. Unfortunately although hearing was temporarily improved this did not last much more than a year.

While in Maseru, Spie asked me to participate in a delegation going to Islamabad in Pakistan to discuss the possible construction of a Nuclear Power Plant. We completed packing up, hired a car in Bloemfontein and drove down to Cape Town where Cubby remained for a few weeks before visiting her parents in Langeland Denmark. I flew directly to London, obtained a Visa and then went via our office near Paris to Pakistan.

My involvement in the project in Lesotho had not been a success, but it had been an interesting experience.

[1] Civil war promoted by the South African Apartheid regime backing Renamo

[2] French designed and apparently arching both horizontally and vertically.

[3] Unlike the now demolished District Six across the town, a coloured neighbourhood from which the inhabitants had been callously Evicted by the Apartheid regime and moved to the desolate Cape Flats

[4] A growing country town. Some of my forebears French Huguenots, Hercule and Cecelia du Pres had settled and farmed there in 1688.

[5] Years later Spie Batignolles along with several other parties were accused of passing bribes apparently to get this contract.

index memoir - homepage - contact me at