index memoir - homepage - contact me at

We returned to Paris from holiday at Lohals and waited. A call came to go to Sumatra Seletan (Southern) for 6 months to give advice on and control the construction of turbine table pedestals for a coal fired power plant. We flew from Paris via Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, and Singapore, and landed in Djakarta in a red sunset behind the dark silhouettes of coconuts and banana palms. We had a night’s rest before flying on to Palembang in Sumatra where we were escorted through the bureaucracy - works permits and drivers licences were speedily obtained. Both these required finger and palm prints taking hours to wash off.

|

|

On the Palembang river - an ancient trading centre. |

|

Palembang, an ancient town from Arab trader days from the 6th century, is Indonesia’s main oil producing centre but appears to be a single storied, tiled red roofed, backwater. The office manager invited us to his son’s first birthday party. We sampled a tasty new cuisine, fiery fried chicken, soft meatballs with shredded coconut and a cooked vegetable salad GadoGado served with hot peanut sauce. We met many smiling people, some spoke English including a jolly transvestite. A local drink of green ‘tadpoles’, apparently made from bean paste and sucked by a straw from sweetened soya milk, was not enjoyed.

|

|

Views on the way to Tanjungenim - stilt houses of small farmers and dugout log 'canoes' on rivers. |

|

The journey to the site near Tanjungenim, 180km south east of Palembang, took about 3 hours by microbus. The scenery with stilt houses and forest was not unlike Malaysia but with flooded rice paddies and more small-scale farms. Few large palm oil plantations were to be seen. Several dilapidated wooden bridges without side barriers and missing floor planks had to be crossed. Through gaps we could see the muddy rivers flowing below. We hoped that the driver knew what he was doing. At least if we fell into the river we would not be trapped by seatbelts underwater as these were not provided.

Upon arrival it became apparent that the site civil works manager had not been previously informed of my arrival and intended role on the pedestals. He was confident that he could do both this pedestal work and all other works himself and I was shunted onto the control of other relatively minor civil works including some rectangular concrete framed cooling water structures.

|

|

Well designed houses built by Alstom for their expatriate staff. One of several parties for staff from various companies on the project, Cubby and I seated at table. |

|

A well-designed housing compound had been built and we moved into a small functional single bed roomed house. Cubby after setting up 6 homes in the past 6 years, started home making and gardening despite the uncertainty of my job function. Power cuts were not a rare occurrence particularly in thunderstorms. At one stage there were so many cuts that at nightfall we lit a candle as a precaution, lighting others when darkness descended. We hoped that the air conditioning would restart permitting sleep in the humid atmosphere. We again enjoyed breakfasts with delicious pineapples, bananas, and papaya (all ridiculously cheap from the local market).

While we were building the power plant other foreign contractors were upgrading both the coalmines (which the Dutch had started in 1910 using imported Javanese labour), and also the train tracks and bridges from the area into Palembang. Many expatriates were thus living near to our main village of Tanjunenim.

Twice a month expatriates and some Indonesians went on ‘Hash Harrier’ runs/treks through the countryside – through rubber, coffee and sago plantations and slopes of mountain rice. Wide eyed curious children from small stilted thatched farm cottages surrounded by goats and chickens, watched us pass scrambling through mud, rivulets and over innumerable stiles. Instead of retiring to a hawker’s stall for breakfast, as done by the original Hashers in Kaula Lumpur, we dripping with sweat finished up in the large swimming pool at our compound.

The news of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power disaster reached us causing momentary concern for our relatives in Europe until we heard that nuclear fallout had not been deposited in their areas.

After some months the civil manager went on holiday leaving me to look after the turbine pedestals. The timber support scaffolding partly erected to take the elevated heavy concrete pedestals weight was visibly poorly constructed and thus impossible to justify by calculations alone. If its erection continued a collapse during concreting could well have occurred. The Site Manager thus agreed that steel scaffolding should be used – but this was not easy to find in Sumatra.

Some light steel building scaffold was apparently available 600km north at the west coast town of Padang and it was decided to inspect it. Cubby and I set out in the Site Managers comfortable air-conditioned car following the torturous twisting and turning road from Tanjungenim to Sorolangum on Sumatra Seletan’s northern border. In several places there were detours due to portions of roads slipping into adjacent rivers. Also temporary log bridges were being erected to enable existing permanent single lane bridges to be replaced with wider ones – some being built by Korean contractors.

Beyond Sorolangum we joined the Trans Sumatran Expressway, a single carriageway with hard shoulders on which journey’s progress was better. On occasion glimpses were had of the mountains running up the west coast in the distance, but generally there was secondary growth forest or land cleared for farming. Much of the land was farmed by settlers moved from the more crowded islands of Java and Bali under the Indonesian policy of transmigration.

Occasional tall grey skeleton trunks of giant trees testified forlornly that this was once a rain forest. There was probably not yet the same scale of plantation development we had seen in peninsula Malaysia across the Malacca Straits. In Malaysia many plantations were owned and run by Chinese Malaysian companies, where as in Indonesia there were fewer Chinese and their position in the society was both politically and physically precarious. Most Chinese adopted local names, but this was not much protection.

We stopped for makan (food) at one of many ‘transport’ cafes lining the route. Boiled rice and numerous dishes of prepared meat, fish and vegetable all highly spiced were displayed. We gave a fleeting thought to how long the food had been in the warm air, but hoping that the chilli would keep bacteria at bay, tucked in without ill effect. Our Indonesian companions partook in the meal although this was the Moslem fasting month Ramadan - they as travellers were exempted. They did not drink beer with me, but together with Cubby consumed some delicious ‘sundaes’ made with chopped avocado, yellow jack fruits, soft white flesh of coconuts - all packed in with frozen coconut milk and drunk/eaten when melting.

We travelled through a mountain pass down into Padang at night not seeing the reportedly impressive views. The whole journey had taken 13 hours.

The next day I inspected the steel scaffolding. Although light tubular building ‘walk-through’ type of scaffold, it would be suitable if closely packed together and well braced.

Cubby travelling in a horse drawn tonga (carriage) explored the rather quiet town - probably Ramadan had reduced trade. The museum was a beautiful copy of the traditional houses in the area, with walls of carved and painted wood and roofs with sweeping curves. The public gardens were scruffy, the superabundant luscious exotic flora available in this region did not seem to have been used. A few Padang old-timers could still speak Dutch, but many younger Indonesians had learnt English.

We wanted to return down the west coast road to Bengkulu to see the botanical gardens founded by Sir Stamford Raffles. He had been lieutenant governor from 1818 to 1823 before Sumatra was handed by England over to the Dutch. The road was said to be impassable as apparently no maintenance had been done on it during the past 5 to 10 years - the Trans Sumatran Expressway had evidently received priority.

In between bouts of hash harrier runs, tennis, swimming, and playing bridge we managed to get some progress on the turbine pedestals. Only incomplete and ill-considered small-scale plans for formwork could be extracted from the local subcontractor (who unsurprisingly had no previous experience on such pedestals). As the workmen could not interpret and follow these, I resorted to having large posters erected near the pedestal itself on which I drew full scale sections of the pedestal showing how the timber formwork was to be made, and restrained and sequenced with rebar placement. The workmen copied requirements directly from these posters easing supervision and speeding construction. This tended to blur the responsibility barriers between us, as main contractor, and the subcontractor – who would be responsible if the formwork or scaffolding failed during concrete placement?

|

|

|

The delayed turbine generator pedestal being built under the already erected turbine hall steelwork rather than as preferable before erection as this gives easier crane access.In left picture - light steel access scaffold being erected at close centres to take the heavy concrete weight of the pedestal. Middle picture - Soffit and internal formwork and lattice towers, as temporary works on the main supporting columns, were then erected.In right picture - rebar and sleeves for anchoring bolts being erected. The sleeves were accurately located with discs on the soffit. After rebar had been erected, steel prefabricated templates with spigots slotting downwards into the tubes were set and adjusted in plan on the towers. Long bolts would later pass through the sleeves for anchoring the generators and turbines. |

||

As it was now obvious that I would be required at Bukit Asam more than 6 months to complete both pedestals, our 15 year old, 187cm tall son Ben joined us from his Danish school at the end of June 1986 for a holiday. At the housing compound we had been hanging our ‘middle aged’ clothes out to dry behind the house without anything being stolen, but as soon as Ben’s clothes with designer labels were placed there all were stolen. The wire boundary fence was no deterrent and the watchtowers provided, which the French called Miradors (an archaic English word), were unmanned.

|  |

|

|

|

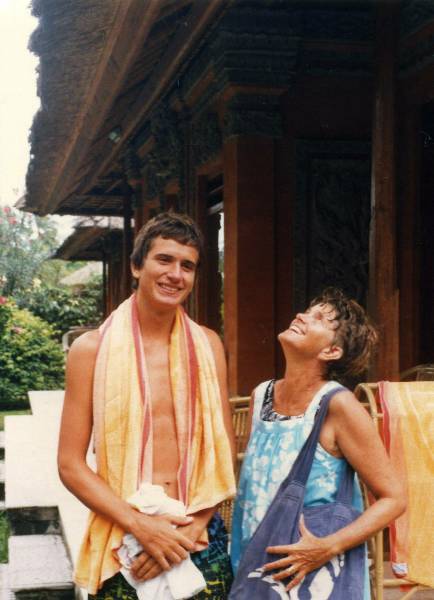

On holiday with Benjamin in magical Bali |

|

For Ben’s last week of holiday we took off to Bali. We were delighted with our accommodation at Legian Beach Hotel with small bungalows dotted about in a lovely garden on the edge of the Kuta beach. Regular breaking rollers bore us body surfers crashing onto the white sands. The only undesirable element were the many beach vendors who woke you from your doze by sticking merchandise under your nose and asking ‘you wanna buy’ for items similar to gnomes in an Englishman’s garden.

Despite tourism the standard of craftsmanship in Bali is amazingly high. Bali is one huge dedication to Hinduism, but a softer Hinduism than found in India – little caste segregation? Or possibly life itself is easier? Apart from the large ancient temples, every kampong (village) has their own shrines, gateways and statues – some ancient and moss-laden have an enchanting secret garden atmosphere.

|

|

|

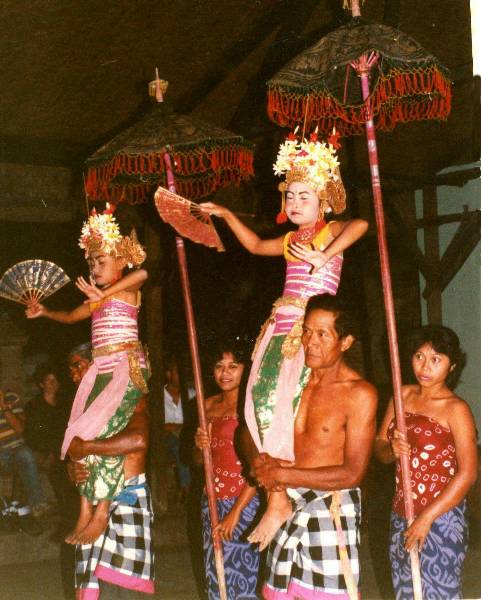

Colourful Balinese traditional dancing attracted many visitors |

||

Ben flew off from Bali to Europe at the end of July and we returned to our ‘sour hill’. Cubby consoled us by making dishes harvested from our garden - okra in yoghurt with mustard seed, coriander and cumin. We were entertained by a troop of silver monkeys making a great deal of noise and jumping intrepidly from branch to branch in the bushes beyond our boundary fence,.

The first turbine pedestal preparations were rapidly completed and concreted on 25th September 1986. The next day we started an exploratory voyage through Java. Before departure the subcontractor’s foreman in charge of the pedestal construction tried to hand me at home a bundle of Ruppiah notes in thanks for the help I had given his company on the pedestal.

We, avoiding the hassle of Djakarta, flew direct from Palembang to the old tree-lined colonial town of Bandung set in a hollow surrounded by mountains. One of these mountains resembling an ‘upside down boat’ from a distance is called Tangkuban Prahu. At the top are five volcanic craters, four of which still show some signs of activity, but the last major eruption was in 1969. Three of the craters emitted strong smelling sulphurous steam from fissures lined with beautiful yellow crystals, but the last one, barren and moonlike, was enlivened by hot spouts and boiling water. Returning to our taxi, down the knee creaking volcano slopes, we passed through a dripping wet verdant fern and liana draped forest with enormous trees blotting out the light and contrasting startlingly with the adjacent barren craters.

We ate steamed fresh water fish prepared in the Sundanese tradition (Sundan being one of the three ancient kingdoms of Java) in a restaurant set in a small gully and surrounded by rice paddies and fishponds. The restaurant was built on stilts on a series of levels with roofs giving protection from the rain pouring down, but having no walls was open to cooling natural air.

We left Bandung by train swaying, jogging and lurching and initially fearing derailment to Yogyakarta. The track was very uneven in comparison with similar three foot six inch narrow gauge railway train rides taken in South Africa in my youth, but the jogging and rolling was similar to the train ride from Sheffield to Barnsley in 1999.

We arrived at 2 am in the morning - a taxi, optimistically waiting for this late train, took us to one of the hotels extracted from a guide book at random. Rising at 7am as we anticipated much to see, we found the hotel a pleasant surprise - bungalow bedrooms clustered around little gardens of palms and shrubs, exotic plants in hanging baskets, birdcages, little pools, rocks and reeds of many colours. The dawn chorus of distinctive bird chirping was exquisite. The reception rooms, verandas around courtyards open to the air, displayed what struck us as being simplistic crude statues. These had been made in Irian Jaya (the western Indonesian part of the Island of New Guinea) and were unlike the graceful Hindu and Malay sculpture elsewhere in Indonesia. The hotel, both with a large block behind and a swimming pool under construction, would possibly loose its charm when these were completed.

Yogyakarta is a centre for Batik. We saw this being made in workshops and bought a few attractive pieces. As one of our drivers had been instructing expatriate wives how to make Batiks at our housing compound, this was of particular interest. We visited the royal Kraton and its surrounds – the Sultan’s palace complex in the centre of the city – and returned in the evening to see court dancing accompanied by gamelan orchestra and wayang puppet performances (traditional shadow puppets)

|

|

Near Yogjakarta in Java - walking on the slopes of Merapi where there are many farms despite the volcano not being completely inactive (erupted in 2006). One of the many Hindu temples in the area - the famous Buddhist temple Borobudur, once covered in ash from Merapi and re found centuries later is also close by. |

|

We went to the hill station of Kaliurang and without guide climbed strenuously up Mt. Merapi first through tropical jungle forests, changing to pines and then what appeared to be beeches with patches of ferns and grass interposed as it got higher and cooler. We failed to find and reach the volcanic rim at 2900meters and see the molten lava and returned just before dark to our waiting taxi driver.

Our tourist bus, with various European nationals, left at 6-45am the next morning. Stretching from Yogyakarta and almost up to Borobudur (NW and for miles), was a continuing series of villages with intensive cultivation on all sides – vegetables, rice and the occasional tobacco field. The land was crammed with Javanese peasant farmers - apparently with inheritance laws plots were subdivided between brothers and often could become small uneconomic farms.

Indeed Java contains 100 million people, ½ the population of Indonesia. Domestic agriculture has been practised there for 2500 years before Christ. About ¾ of Java’s population is now not tied to the land with many living in poverty in towns, it thus did not seem surprising that Indonesia has a policy of ‘transmigration’[1]. This re-settles people from crowded area in less developed areas. However, with such mass migrations conflict with indigenous people was likely to occur and indeed did occur often with violence and bloodshed.

Borobudur is a temple built on a raised mound on a natural plain with mountains in the distance. We were intrigued by the carved stone-perforated bell-shaped stupas with slightly larger than man-sized meditative Buddhas sitting inside some of them. This temple, rediscovered and reclaimed from volcanic ash from an earlier eruption of mount Merapi and with its underlying foundations rebuilt, is one of the most interesting in the world.

Our tour bus started climbing upward on the way to the Dieng plateaux. It became so steep that when the driver stopped to let us take photos he shouted to a young boy at the back of the bus who immediately placed a large wooden wedge under the bus rear wheels. Further up the houses in villages were surrounded by roses, hollyhocks, hibiscus and bougainvillaea. Suddenly we arrived on a grassy plain with mist swirling around what we thought were randomly strewn boulders. These we saw on closer inspection were Chandri, stone Hindu burial temples.

We heard not far off from behind some hill tops a constant roar and what appeared to be a column of smoke – we drove towards it and found a now barren and rocky plain with large pools of bubbling and spitting lava – mostly grey but some coloured by minerals green/grey or blue. Further on in an almost sylvan setting there were two lakes – one an unlikely bright green, the other with a unusual reflecting surface - called mirror lake. On the lake edges little steaming fissures bubbled and patches of vivid algae grew. We did not reach the roaring steam geyser but saw some steel pipes being laid – apparently the steam would be delivered to a turbine generator producing electricity.

We returned to Yogyakarta stopping at Prambanan, at further Buddhist temples and also the Lara Jonggrang temple – built to worship the Hindu god Shiva. Many religions (Buddhist. Hindu, Islam and to a lesser extent Christianity during fairly recent Dutch colonial times), had swept through Java. Islam was now of course dominant in Indonesia except for Bali where Hinduism prevails.

In Indonesia it is not surprising that with the influence of many races, cultures and religions official ideals for the country called Pancasilia was introduced by Sukarno (Indonesia’s founding President). Included in these principles are democracy, humanism and the belief in one god. This should ensure mutual tolerance of the many theistic beliefs and races – this ideal has fallen down in practise and violence and strife has often arise between various religions and races – a situation not uncommon in many other parts of the world.

At Bukit Asam we had been informed of famous fried chicken available in Yogyakarta made by Nyonya (Mrs) Suharti. Spotting this restaurant, we ate the succulent fried chicken together with Gado Gado salad and hot chilli peanut sauce – we thought the Colonel’s chicken, available in many parts of Asia, though often good, is not as good as this.

We left Yogyakarta by express bus at night heading for the town of Malang the closest town to Mt. Bromo. Malang was a pleasant backwater with wide avenues and huge trees. Two competing imposing churches built in Dutch times stood next to one another on the town square, one Catholic and the other Protestant - both well attended - we wondered whether the present local Christians surrounded by Muslims really understood the historic and doctrinal differences between the churches or had it become traditional within families to attend one or the other? We ate a meal in an old Colonial building with high moulded ceilings. Chandeliers hung on long iron shafts to bring light down to diners. Some walls were tiled with scenes depicting dykes, windmills, cows and canals - nostalgically comforting to long departed Dutch colonials.

We found that it was not possible to get from Malang to Mt. Bromo – no suitably maintained roads - so after a nights rest we retraced our journey northward towards Surabaya, but turned off eastward before it towards Probolingga. Here we caught a local mini bus (bemo in local slang) going toward Mt. Bromo. The bemo had 13 seats, but picked up passengers at many loading stops. A cramped total of 22 good-natured persons together with bags of potatoes, spiky Jack-fruit, and fishes swimming in plastic bags filled the bus. We climbed inexorably up the steadily worsening roads on the sides of Mt. Bromo accompanied by Indonesian pop tunes played from tape cassettes at full blast and reached the little town of Ngadisari – the end of the bus line. In the noonday sun we trudged upward about 2km with our heavy bags. We passed many pretty ‘bed and breakfast’ type houses surrounded by carefully tended gardens until collapsing exhausted at the uppermost rather rudimentary hotel.

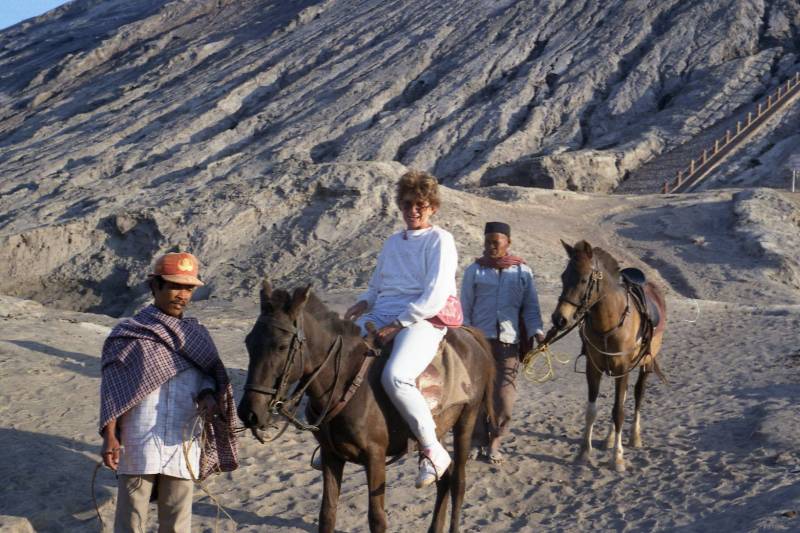

Rather than lose a day and start shivering early in the morning to see the sun rise over Mt. Bromo, we visited the crater later that afternoon. Guides led us on their horses zig-zag down the rim into the dormant mother crater’s floor and for about an hour on a sea of dark desolate grey sand towards two further ‘peaks’. The flatter lower one was billowing forth steam, the higher one was dramatically scored with erosion. Our horses climbed the lower peak and we dismounted. We walked up the last 233 steps to the rim of the active volcano and peered down into the distant crater where a lake encrusted on the edges with yellow crystals bubbled and hissed and puffed forth steam.

|

|

|

Bromo - the floor of the old inactive crater - a view down into a secondary semi active crater - Cubby mounted on horse for the return journey across the inactive crater floor. |

||

The clouds turned pink in the west and the shadows of the jagged rim rocks lengthened as the sun threatened to set. Cubby remounted her horse, but my ill-behaved steed although restrained by the guide made several attempts to kick me in the genitals. Rather than risk mutilation I walked back

After a meal we retired, being unable to read under the gloom of a 20watt light bulb, we fell asleep. At 4-00am, having breakfasted, we returned by bemo to the main road at Probolingga and caught the express bus from Surabaya at 8-00am. We travelled 4hours to Banyuwangi on the east tip of Java and boarded a ‘roll on roll off’ ferry. This resembled we imagined a world war II invasion craft used at Normandy. After an hours sail we arrived on the western tip of Bali at Gilimanuk. Here we alighted as the bus was continuing southeast to the capital Denpassar.

We boarded a bemo, again grossly overcrowded - 24 passengers, 4 babies and a duck, at times. The bus stopped - a puncture - and was laboriously unloaded to get to the spare tyre - then continued 75km along the north coast. The whole area appeared much drier than the lush irrigated southern Bali we had visited some months earlier – apparently only one crop a year can be grown compared to three crops in the irrigated southern parts of Bali. We spent the night at a small family run beach hotel some way before Singaraja. There were many small hotels catering for tourists along this coast – all very cheap by the more affluent standards in south Bali. The beach sand was volcanic black and we hesitated to plunge into the inky ripple-less seawater – the white coral and quartz sands in the south were more appealing.

Our cottage room of woven reeds with a thatched roof had bathroom facilities outside in an enclosure open to the sky. A palm tree heavy with coconuts loomed menacingly above one when enthroned threatening to drop a nut on one’s head. Our night’s rest was disturbed several times by loud savage rattling noises ending with crunching sounds. These were apparently made by ‘kitjaks’ - small lizard like creatures with suckers on their toes and fingers enabling them to climb upside down. The noise arose from catching and devouring insect prey without good table manners.

|

|

Market at Bedugal - enticing fresh vegetables and flowers. |

|

The next day, our bemo climbed steeply southwards up to the village of Bedugal 1800 metres high on the edge of lake Bratau – a lake within an extinct volcano crater. The town had a very attractive market with baskets of fresh strawberries and exquisite flowers. A large number of orchids, with roots packed in plastic bags, were for sale. The sales assistant implied that in these bags they would last without requiring water to be added for some months. We wandered around the town’s botanical gardens then descended down to the lake through paddy fields and vegetable gardens. Clambering over lakeside rocks and through slippery paths in the jungle, we reached a restaurant on the lake edge. Mist and a light drizzling rain descended blotting out the view as we ate. We returned refreshed to Singaraja after a day in an almost temperate climate.

Singaraja itself was described in our guidebook as being the capital of Bali under Dutch colonial rule and a ‘port city’ with communities of Chinese and Muslims. The only sign of a port we saw were small local boats (prahu) being loaded by men wading chest deep in the sea with heavy bags upon their shoulders.

After journeying to and spending an un-memorable night at a hotel costing US$3 at Padang Bai on the east coast of Bali we caught the ferry for the four-hour journey to Lombok. There are two main things of interest in Lombok – one is mount Rinjani at 3800m high a considerable peak and some off shore islands for scuba diving enthusiasts – we however were not equipped for either nor part of a visiting group and confined ourselves to touring. The island people seemed to be largely Muslim, poorer and probably less used to and less welcoming to visiting tourists than the neighbouring Balinese.

|

|

|

|

Lombok - Livestock market - Traditional village - Colourful locally woven cloth - Family group, the umbrella for protection from the sun rather than from rain. |

|

We enjoyed swimming in a crystal clear spring filled icy pool of a hill station hotel. We visited a factory making beautifully woven ‘Ikat’ cloth on what appeared to be enormous old Mancurian looms straight from the industrial revolution – shuttles flying back and forth, all hand and foot operated with a tremendous clacking noise. Much of this craft appeared to be controlled by ‘Arabs’ - still so called although they had come some three generations ago from South Yemen.

We flew back to Bali in a 24seat twin propeller plane taking 24 minutes (rather than a tedious 4 hours on the ferry). While circling to land we noticed that the sky was alive with beautifully decorated high flying kites and wondered if one would tangle with them – indeed on landing we found one wing covered with a mass of streaming plastic. We inspected several hotels for our intended 6night stay and again found near Kuta Beach one with cottages set in a garden – with good clean, ironed sheets and bathrooms. There was also a magnificent swimming pool on the second floor overlooking the sea. We relaxed.

|

|

|

In Bali - terraced paddi fields - ploughing the paddi fields - young boy selling bananas and mangos |

||

Back in Sumatra we heard that things were not going too well for SB in France and that many staff had been laid off. We pondered what would happen when we returned to Europe at the end of the year – would we still have a job? The second turbine table proceeded rapidly – lessons well learnt from the first one - and I found myself less busy on supervision. Cubby’s orchids purchased in Bali, although looking dilapidated, revived and her vegetable garden despite her absence had flourished.

The second pedestal successfully concreted, we returned to Europe in time for Christmas 1986. The journey back – bus to Palembang, flight to Djakarta, flight to Singapore, flight to Amsterdam, flight to Copenhagen, collecting excess baggage sent in advance at the airport, driving hired car to Ben’s school in Bagsvaerd, on to the ferry and then to Lohals - lasted over 24hours. Continuous travel was an exhausting mistake.

[1] This policy had actually been started in Dutch Colonial times

index memoir - homepage - contact me at