index memoir - homepage - contact me at

In mid May 1962 we packed up our belongings in Kent and flew as a family from Heathrow to Kastrup airport, Copenhagen. We stayed at Cubby’s parent’s large rented apartment on Stockholmsgade overlooking the Østre Anlaeg Park. Cubby after a childhood in South African away from many close relatives was back in the heart of her large Danish family.

|

|

|

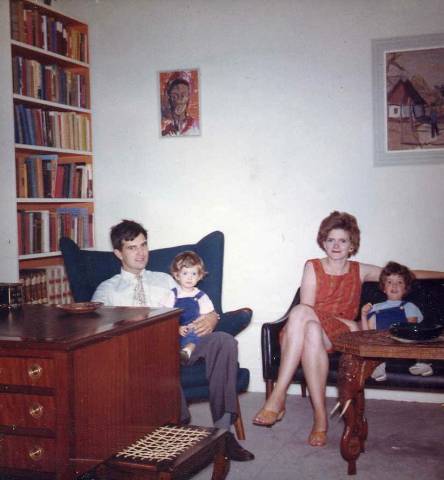

Cubby's parents Mercia & Aage, Cubby and I with Karen and Nicky in their spacious apartment at Stockholmsgade in Copenhagen. Family posing in front of the famous Geffion fountain |

||

For some months I worked at Christiani and Nielsen’s office Østed Hus assisting in the planning of the project and attending an in house concrete technology course before going to Pakistan. The project was one of several irrigation projects for the Indus Basin Scheme in then West Pakistan. The projects, financed by the World Bank, had arisen through the partition of the sub-continent in 1947 when India ceased to be a British Colony. At that time the Muslim state of Pakistan was created separate from India. Pakistan then consisted of two parts, West and East, but the eastern part after a civil war was later to become the independent state of Bangladesh in December 1971.

The irrigation water supplies to West Pakistan had been affected by the partition. Many large projects were implemented to assure independent irrigation water supplies from Pakistan’s own sources with a view to reducing potential conflict between India and Pakistan. The Islam Barrage in Pakistan, built by the army in 1925 on the Sutlej River, could now only obtain a reduced flow of water from India – Mailsi Siphon was thus conceived.

The project Mailsi Siphon, at Mailsi about 50 miles east of Multan in the Punjab, was for a barrage / siphon on the Sutlej River. Four 13ft 6inch square conduits incorporated in barrage foundations would transfer replacement irrigation water through canals from other barrages across the seasonally flowing Sutlej River. London consultants Coode and Partners had designed the project and controlled the site as Resident Engineers for the Client, The Water and Power Development Authority, (WAPDA) a government agency.

I left for West Pakistan in August 1962 as part of the advance party of ‘bachelors’ who were to establish the site infrastructure and housing for families and others following later. Staff also came from other consortium partners – Gammon Pakistan with local know how and the French firm Companie Francaise d’Entreprises who were specialists in earthworks. The site agent Mr Oalf Gravesen a Dane from CN and his deputy Mr Jochen Siber a West German from Gammons lead the construction team.

We initially lived and worked in a landowners large colonial style house, high ceilings, overhead fans, and with small shaded widows keeping out both heat and light. Later on we slept in some Nissan hut dormitories erected in its compound. Some staff, coming before me, had slept out of doors as it had been unbearably hot inside the house without air-conditioning - the heat of the summer in this semi-desert area reaches 47 C. Dust storms had swirled around them and they burrowed under their sheets. At dawn flies settling on their faces waking them. At 6am it became too hot to lie abed.

In the winter, in contrast shortly after I arrived, it became positively cold in the Nissan huts at night. The house was in the village of Fada close to our future housing colony. Fada, which could have been thousands of years old, contained mainly humble mud brick houses with narrow dirt pathways in between, not always passable by vehicles, and reminded us of illustrations of biblical villages.

|

|

|

|

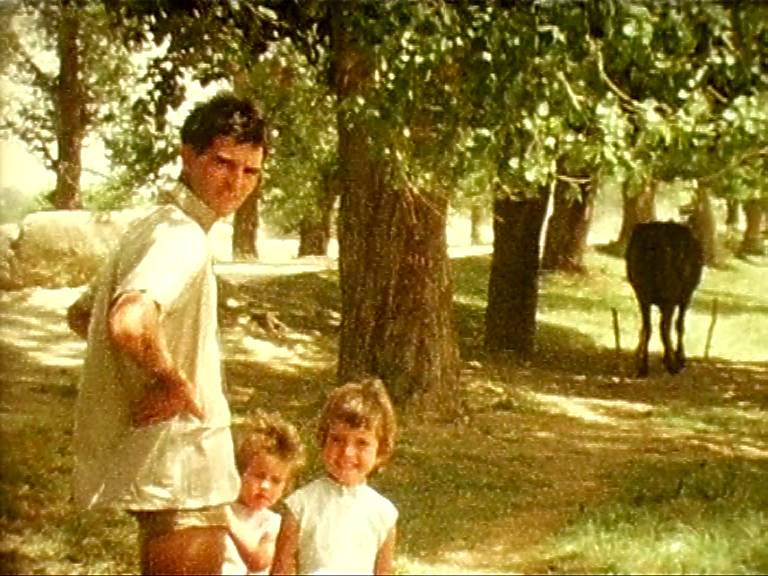

Pictures 'freeze frame' from home movie - shows the canal near the village of Fada (centre above) and our housing colony - Tony Allsopp on right with daughters Karen and Nicky walking along canal bank. |

||

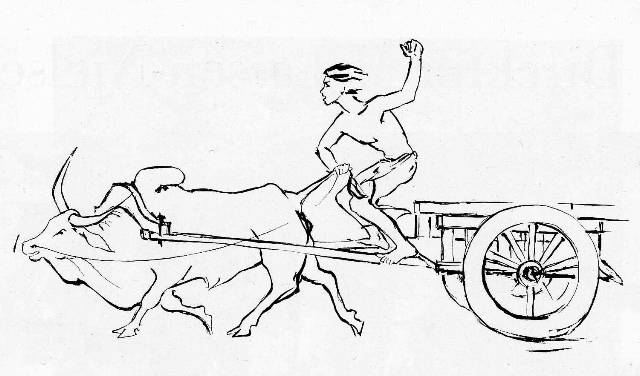

Starting from nothing a Scotsman Bill Dunn from Gammons pushed the construction of brick flat roofed houses at a very brisk pace. Bricks were made and burnt locally. They were delivered to the site in two wheeled wagons drawn by oxen - the young drivers, with bare chests, twisted the oxen’s tails to get a little more speed. Gypsy women climbed decrepit site made ladders with metal head pans full of concrete and emptied them to form the roofs. Nearing the end of each roof the work rate accelerated accompanied by the beat and whine of music and ended in a roof wetting ceremony. These women wore colourful long robes and jewellery some of which pierced their nostrils[1]. Completed houses started being habitable within one and a half months and the housing camp was completed within six months – a good effort in difficult conditions.

While this was going on, we designed and built the site support facilities using the limited locally available materials. For the barrage itself some materials such as aggregate and sand would come by rail considerable distances from Jellum and Sargoda – only construction plant and some special materials incorporated in the permanent structures were imported and conveyed also by rail from Karachi about 800km south west. To enable deliveries to be made, the rail track was extended from Mailsi right into the construction site. We suffered few delays as our management had posted employees at key points along the route to expedite clearance and speed delivery.

In mid October 62 Cubby and our two children flew from Copenhagen in a Coronado plane stopping surprisingly four times - at Dusseldorf, Zurich, Rome and Teheran - to pick up and drop passengers before reaching Karachi. Fortunately, Cubby burdened with two small children, was helped on this journey by another wife Margrethe Beckman joining her husband. I met them in Karachi at the hotel where some Japanese businessmen photographed our two children as exotic curiosities. We flew to Multan after a nights rest in a Pakistan International Airlines propeller powered Fokker Friendship and thence by car to the site 2 hours away along a narrow single lane road - giving way to rapidly approaching traffic by swerving alarmingly into the dusty verges.

|

|

|

Sketches by Cubby during construction of housing colony - buffalo cart used for transporting materials, water bearer for filling tanks on house roofs until water piping was installed, woman labourer climbing ladder with pan of concrete for flat concrete roof. These sketches appeared in Christiani & Nielsens company magazine |

||

|

|

Gypsy woman worker transporting bricks - drawn by Cubby for a Christiani & Nielsen seasonal greetings card |

We moved temporarily into a small house pending the completion of a larger expatriate house. Water was supplied in a goatskin by a bearer climbing up a ladder and emptying it into a tank on the roof – the piped water supply had yet to be completed. As there was no glass in the windows, mosquitoes bit our children whose faces swelled up – so window netting was rapidly installed. We became accustomed to regular power failures, the loss of cooling ceiling fans and air-conditioning, and always had candles and matches at hand. Cubby busied herself by monitoring the construction of our future house, redesigning the kitchen furniture layout in a more practical manner. The Pakistani supervisor was bemused – why should a memsahib be interested in the kitchen when servants would do all the cooking?

We recruited a cook, Kissan, a tall man wearing a turban, well over 65years, a relic of the British Indian Army, an Officer’s cook, He bought food at the insalubrious fly blown village market. European women, casually dressed not in purdah, felt unwelcome under the stares of the local men. Kisan was well schooled in English cooking, he produced excellent steak and kidney pudding capped by delicious mille-feuille pastry made with blood stained suet. We shared a bearer with our semi-detached house neighbours, he did all cleaning work which the cook considered below his status and which memsahibs from Europe also lazily abandoned.

|

.jpg) |

|

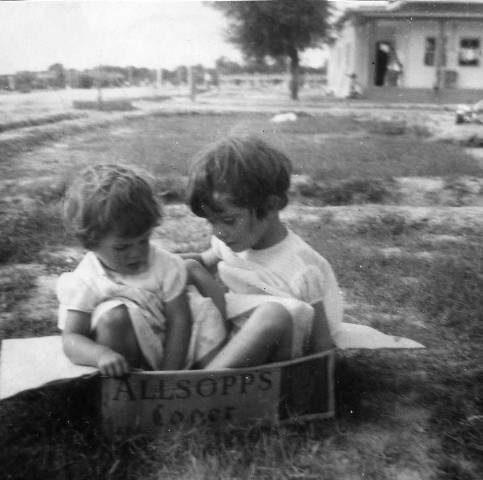

Karen & Nicky in empty 'Allsopps' beer box, beer could be imported for thirsty expatriatess - Our just completed house with water carriers on roof filling tank - Cubby bathing in vast pond formed alongside Sutlej river. |

||

We settled in to a life of comfort. We picnicked, swam and boated, alongside buffaloes in vast lakes left behind after the seasonal flooding of the Sutlej river. Gardens watered plentifully, grew rapidly, and the clubhouse, swimming pool, tennis and squash courts were soon completed. Cinema films were projected on an outside screen, badminton was played in the still evening air, mouth watering curries were served at company parties – frail European stomachs after initial upsets became hardened. The few Scots introduced many foreigners to Scottish dancing in the cooler winter months.

Nicky attended play-school, Karen was too young and had to content herself with playing on the swings at the pool. Cubby taught art to the older school pupils. The French, as is their sensible practise, on overseas projects had imported a French teacher for their children.

A Garden of Eden expatriate life was enjoyed, but there being few domestic problems or duties, we had to manufacture problems. Invariably ‘serpents’ were created centred on equality of privileges – why did some bosses and staff have transport and bigger houses, inconsequential jealousies stoked by idle chatter. Neighbour’s partners attracted one another at dinner and dance parties – the grass was always greener elsewhere.

|

|

|

|

|

Scenes from our nearest large town Multan - freeze frame pictures taken from our rather poor quality home movie made with borrowed 8mm cine camera |

|

A few expatriates, especially some who had not travelled outside Europe before, found it difficult to adjust to life in Pakistan, they seemed to have imagined that life would be exactly the same as at home except for the warmer climate. They could not reconcile themselves to a different culture and people and became critical, prejudiced and rude. Unaccustomed heat, stress and different languages probably contributed to this. Not every one ate smorgrasbrod[2] at lunchtime.

The country had been under a military administration headed by President Ayub Khan from 1958 (to 1966), the army had taken over from post independence civilian democratic rule. Things seemed to work, and importantly for expatriates alcohol could be purchased in special shops. We could slake our thirst after a hot day on site with a Murray beer. Later we could also purchase imported goods, non-halal tinned Danish bacon and Allsopp’s[3] export beer from the site commissariat.

Rural life continued undisturbed around us – the sleek black water buffaloes swam languidly with their young boy keepers in the shady tree lined canals surrounding Fada; hypnotic popping hooters were heard when wheat was being ground at a mill; during evenings and early mornings we heard the faithful being called to prayer. Every Wednesday a hawker would receive miraculously fresh fish by rail from Karachi and sold it to us. Other hawkers displayed their carpets, copper and brassware, carved ivory (or bone passed off as ivory) and Kashmir shawls on our verandas. We learnt to bargain despite their protestations of financial ruin. We creakily mounted camels, disgusted by their regurgitated green phlegm and their rumbling stomachs, and rode them wobbling ridiculously lead by their owners on foot.

Cubby’s Danish cousin Søren Willet suddenly appeared on a months visit. He had travelled alone overland mainly by local buses from Europe through Turkey and Iran.

Cubby flatteringly acquired an admirer – a young Pakistani youth working for the consortium had danced with her at a party and was smitten despite the fact that she at 23 years was older, married, of a different religion, and had two children. He insisted in giving her a gift of jewellery before he left the project and returned to the more exciting life in Lahore.

A Muslim friend on the project, Anwar Hayat, had studied Civil Engineering in the United States, and after returning home to his family in India emigrated alone to Pakistan. He told us that his parents had selected his future wife and his marriage[4] had now been arranged and left for Madras in India for his wedding. He returned with a charming and sympathetic girl and we conceded that there might be merit in this system, strange as it seemed to us Westerners.

Sometimes there was domestic drama. We noticed that large hunks of wood were being bitten out of the bottoms of doors leading from a short rear corridor into the kitchen, the lounge and the children’s bedroom. We feared that the unknown ‘beasts’ would if they persisted enter into the bedroom and bite our children. We stayed up late sitting quietly in the lounge with the lights off with tennis racquets in our hands. When we heard the sound of gnawing we opened the door and switched on the lights – two enormous rats scuttled into the lounge and we quickly shut the door trapping them. The hunt began with the rats hiding and we having to flush them into the open. We eventually struck and immobilised them with racquets thrown flat and spinning across the cement floor and followed with the coup de gras. We slept more soundly that night.

Each morning we travelled about 4 miles to the site. Progress was rapid - Pakistanis were hard workers. They handled the heavy earthmoving scrapers with panache replacing most of the French operatives who had trained them and then returned to France.

|

|

|

|

Batchplant with me and Karen - Intake gates for canal siphon crossing the Sutlej River, the barrage above the siphon tubes is shown behind. - Labour working on revetment stone protection on bunds leading to barrage. |

||

Concrete, sometimes as much as 1000cubic yards per day, was crane placed rapidly from 2cy buckets suspended from crawler cranes into the siphon tubes and the barrage sections above. The steel formwork shaping the concrete, made and designed in France, worked effectively. Because of specified maximum concrete temperature placement limits, chilled water was added in summer to the concrete ingredients mixed in large pan mixers at a central batch plant. This water was chilled from the ground water extracted by deep de-watering wells sunk around the barrage and which then permitted bulk excavation in the dry. The chilling plant became a popular place of refuge from the 47C temperature out doors where one could slake one’s thirst – no need to pre-boil this well filtered water.

The soil under the following siphon tubes themselves was consolidated with a large vibrating probe with incorporated water jets washing out fine soil then replaced with broken brickbats. Women gypsies worked on site excavating and trimming the sloping sides of the canals connecting to the siphon while their young children and babies slept and played not far away under improvised sun shelters. Protective stone revetment was carefully placed by hand on the earth training bunds channelling the river over the barrage. Beams were formed, concreted and post tensioned and then placed on the barrage piers forming a permanent road across the river. Control gates were fitted between the piers.

The consultants had foreseen that the barrage would be constructed in two stages with the river in flood being diverted over the first completed half while work proceeded on the second half – always a tricky situation if delays occurred for any reason. The consortium spoke to a civil engineer, Sir Thomas Foy, who had spent his life on the barrage and canal systems in India and was retired in England – he knew that the river meandered changing course each flood season in the sandy desert plain. He thus proposed that a diversion leading ‘cut’ be excavated around the whole site. The Consultants accepted this proposal - the 1963 annual floods eroded this ‘cut’ into a giant new river course permitting work to continue undisturbed on all sections of the barrage.

Cubby was again pregnant. We did not contemplate having the birth in Europe or even Multan where there was a big well run hospital, but decided the hospital built in the housing colony was best. An Anglo India midwife Babs Barnett on site married to a staff member was agreeable to assist at the birth. The Danish nurse in charge of the hospital would also help. The problem was that the young male Pakistani doctor employed on site would not examine women let alone assist at births. Fortunately an Italian doctor working on a ‘nearby’ site Verhari some hours away agreed to attend.

Some months before the birth we took a brief holiday in Lahore to escape restrictive ‘colony’ life. We left at 4am with two sleepy children and were driven through the rising dusty pink dawn into the heat of the day, encountering many horse pulled ‘tongas’[5], bullock carts and rattling buses. It took 6 hours to cover the 250 odd miles via Multan and Montgomery (now called Saliwal) to Lahore - Lahore, which our homesick cook bearers referred to as ‘Ah Sahib Lahore’ when comparing life in isolated Mailsi with the metropolis. We reached the comfortable company guesthouse without incident and spent two days shopping and seeing the sights.

We saw the beautiful shady Shalamar gardens - unfortunately the fountains in the canals were not working and the water looked stagnant. The ruins of Fort Lahore were immense and spectacular. The innermost portion was beautifully carved and painted by Shah Jahan about 1650 and had been barbarously plastered over by the British Raj in 1848. Young elephants at the zoo gave rides - Nicky was awed by their size and stood well clear, younger Karen knew no fear and did not seem to mind. We drank Coca Cola in darkened restaurants and ate ice creams. In the evenings an ancient Gammon’s director staying over at the guest house relived and related the ‘good old days’ from the middle east to Malaysia without refrigerators and air-conditioning.

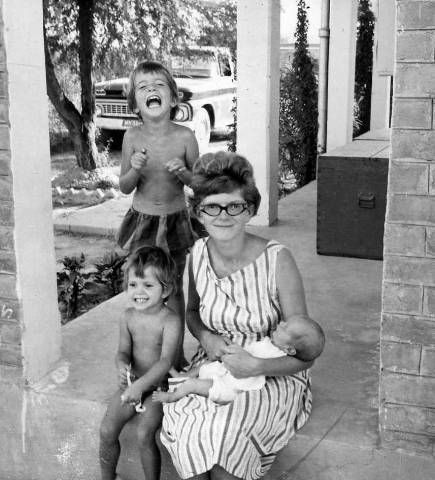

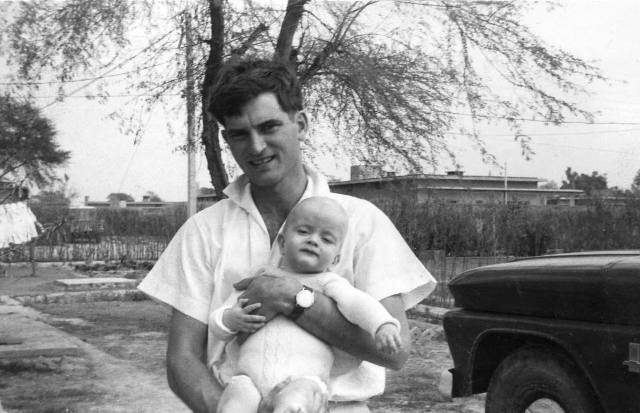

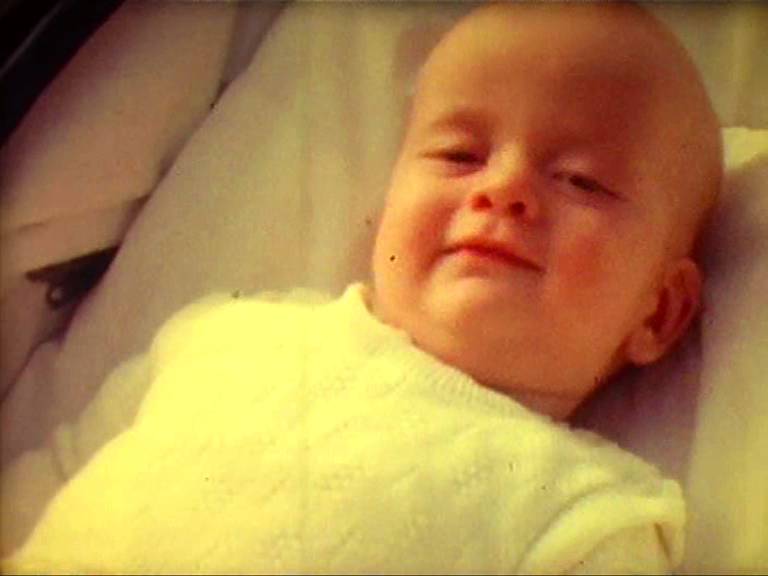

Back at Mailsi some months later, everything went smoothly, the baby fortunately took some time to arrive permitting the Italian doctor to travel 3 hours from his site to be at the delivery. Rather than waiting nervously at home during the birth I went to work on the site and returned to the hospital later. Christopher was born on 26th August 1963 his birth being registered in the village of Fada in Urdu script. The certificate carefully gives the names of the father and grandfather but neglects to mention the mother!

|

|

New arrival Christopher born 26 August 1963, in the site hospital, with parents and siblings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

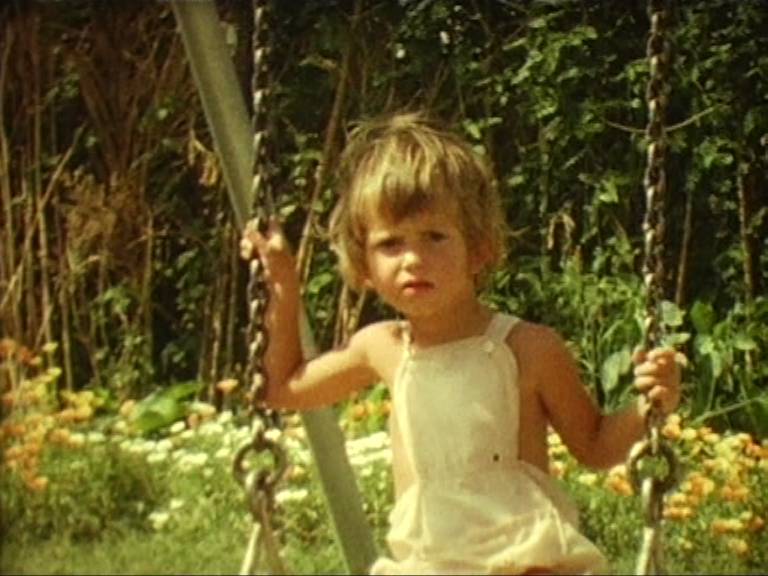

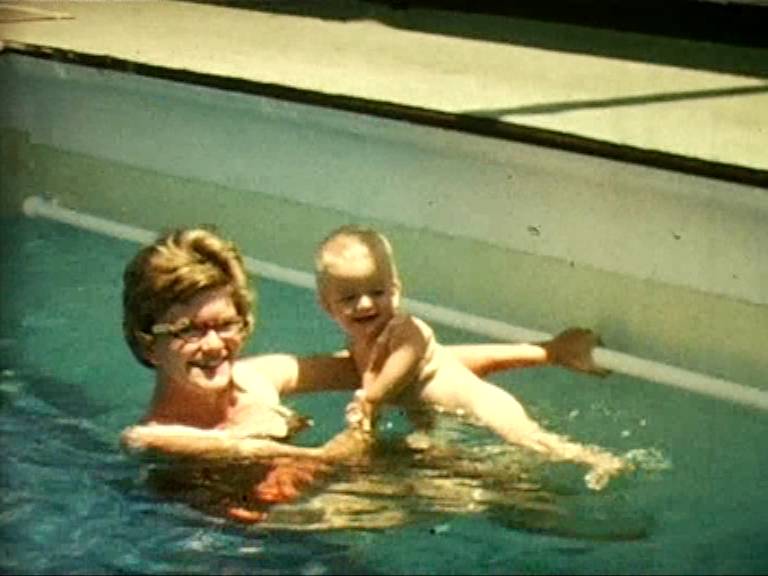

Freeze frame pictures from home movie - from top clockwise - Nicky in housing colony club pool - Karen about to fall asleep on swings - Cubby at pool - Christopher born in site hospital, smiling. |

|

On the 22nd November 1963 President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. We heard this shocking ne ws on the radio while sitting after work at dusk on our veranda having drinks with neighbours Carl-Wilhem and Inge Quist Laursen looking out into desert.

For Christmas 1963, Cubby made cards with local scenes, gypsy women with head pans, donkeys with rider and loads of brushwood. These she had engraved on plates and printed in Multan - she sold 600 to the site community. The printer rather unprofessionally started printing his own copies and selling them direct to the public. Cubby also made a card of the concrete batch plant for the Site Manager to send to companies and persons connected with the project in Pakistan and abroad - a valuable 150 rupees was paid for this.

Despite having three children to care for, Cubby spent much time decorating the club for the projects 1963 Christmas party, and indeed a farewell party as friends on our staff were already being whittled down on a project rapidly being completed.

In spring of 1964 I made a trip alone in an attempt to see the peak of Nanga Parbat (26660ft high) in the portion of Jammu and Kashmir falling within Pakistan. I flew from Multan to Rawlpindi and took a bus to Abbotabad (50miles) where a permit to stay in Government rest houses was procured. A further bus took me to the village of Kagan (70mile) at the start of the pass leading to Nanga Parbat. While the above distances are not great the roads were both narrow and winding and stops for passengers slowed progress.

Bus and truck drivers tended to play games of ‘chicken’. They kept to the centre of the road at top speed and only swerved aside off the tarmac edge at the last minute for approaching vehicles. The road edges were invariably pot-holed and rutted shaking one severely. The trucks were usually much decorated with Utopian paintings of flowers, waterfalls, and green fields – a mobile Nirvana in case Kismet struck and one died in an accident.

After a night at Kagan I found a place in a four wheeled drive jeep with no canopy or sides and left in the early afternoon. We proceeded on the narrow dirt road climbing along the edge of the valley. I hesitated to look over the unprotected road edge down the horrific slopes, on which further down terraced farm plots were incredibly carved. If the driver made one unrecoverable error one would fall thousands of feet to the river below. Few young people were around. Life is hard for 8 months of the year and they migrate to the plains to earn a living. Older men remained with tattered beards and mandarin moustaches.

At dusk we stopped at a guesthouse perched on the valley edge intending to start again in the morning. But it rained and rained all night and continued heavily unabated in the morning. The driver informed that the road was impassable higher up – there were landslides which would have to be cleared once the rains stopped perhaps in two to three days time. We were stuck. Not having unlimited time I said goodbye and rapidly walked down the pass for six hours, about 20miles, without pause in drenching rain. Not a vehicle was seen in either direction confirming that the road was indeed impassable. The river under the bridge into Kagan was now in full flood.

Back to Rawlpindi by bus, directly through the night, I arrived too late to catch a plane to Multan. In a dishevelled short trouser state with my Bergin backpack, the only smart new western styled hotel informed that they were full. A room at the second best hotel, a relic from the time of the Raj, was found. This was still without flush toilets, but discreet arrangements were made for removal of the commode by an attendant ‘sweeper’ waiting constantly on the other side of a trapdoor in the bathroom.

Rawlpindi was an attractive town smaller than Multan, more used to foreigners with several reasonable cafes in which I whiled away the time. The construction of Islamabad, the new capital city, had just started and today dwarfs neighbouring Rawlpindi into insignificance (I was to visit Islamabad with a French group in about 1990. to see WAPDA who were interested in building Nuclear Power Plants).

The next day I flew back to Multan. I have yet to see Nanga Parbat[6].

There was much speculation at Mailsi in early 1964 whether our consortium would be successful on a tender for a new barrage at Qadirabad. We and other staff pondered whether one should go there. In the end the consortium obtained the project, but another possible CN project in Belgium had also arisen. From both a career and family viewpoint it seemed more desirable, we planned to go there.

|

|

|

|

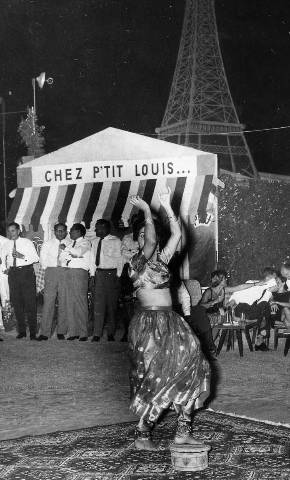

Some of Cubby's large decorations for party - Shalimor Gardens, Statue of Liberty and Eiffel Tower. Site nurse (& midwife at Christopher's birth) Babs Barnet entertains with an Indian dance. |

|||

As the project was rapidly reaching a successful conclusion the Site Manager threw one further large party in early May 1964 to thank the various other Indus Basin companies and persons who had helped during the project. Many nationalities had been involved, including other helpful neighbouring projects, and this set the theme of the party. Cubby was roped in to do the decorations and represented each country with large placards erected and spotlighted in the club grounds of landmarks identifying them – Big Ben, Statue of Liberty, Eiffel Tower, Rialto Bridge (with gondolas floating on the swimming pool), Little Mermaid and Shalamar Gardens (with working fountains in front). We danced and drank at the café ‘Chez p’tit Louis’. The party, with guests and delicious food from many nations, was a great success.

Cubby still has the gold bangle presented to her from the club in thanks for her effort.

We had decided not to fly back, but to take a boat which would be both a holiday and at the same time take our burgeoning belongings.- carpets, bronze-ware, etcetera. We packed up in early June 1964 and set off for a train leaving in the afternoon from Multan to Karachi. The station wagon, shared with other staff going only as far as Multan, broke down halfway. Fortunately our baggage was in a following pickup which I then commandeered and continued on to Multan with Cubby and the three children squeezed together in the front seat - the driver travelled with the baggage on the open back and the other party was left on the wayside to await his return. We arrived just in time to be told that the train was ½ hour late and drank some tea from a hawker – sugar, tea leaves, and milk all boiled together – strong and sweet not to our normal taste.

We occupied a luxurious air-conditioned compartment with a private bathroom on the train, presumably usually occupied by feudal landlords, army officers with families and their ilk. There was only direct access from the platform and no corridor ensuring privacy. The rail track was 6’-6’’ gauge compared to the standard 4’-8 ¼ ’’ gauge in Europe giving a smooth and fast ride. Arriving in Karachi well rested next morning, we spent a few days in a hotel with two enormous inter-linked rooms - shopped, dined out in freezing air-conditioned restaurants – ate delicious chicken tikkas (chicken marinated in curds and chilli then grilled on charcoal), and enjoyed the sights - Karachi was civilisation after Multan.

We passed through Pakistan’s Health and Immigration. Declared all our carpet purchases to Customs who seemed to think we had bought more than permitted, but let them through. Amazingly we had enough foreign currency to balance with our currency declaration paper on entering the country.

The Anchor Line R.M.S Cilicia, an old passenger boat started from Bombay, stopped at Karachi and sailed on to Liverpool. The officers on board were Scottish. The passengers were either expatriates returning home, or emigrating Indians and Pakistanis. Most of the emigrants were women with young children going to join their husbands in England. They spent much of the daytime squatting on the deck, and kept to themselves – we felt thankful for our two comfortable first class cabins with beds. We bucketed along at 10 instead of 17 knots into a terrific headwind for the first few days, but unworried with no deadlines to meet.

We met a Scottish missionary on board who surprisingly had known Cubby’s maternal Swedish grandparents Gustav and Hulda Bjork in 1942 at Chinwara, India. Her grandparents had gone to India at the beginning of the century as teaching missionaries and had left and retired some fifty years later back in Sweden. They had died when we were in Doncaster, but Cubby’s cousin Lennart and his wife Birgitte still live at Uppsala.

|

|

|

|

|

Relaxing on board the RMS Cilicia |

|

We cooled down in the swimming pool. Nicky learnt to swim in salt water despite not being able to reach the bottom with her feet, Karen ventured in with armbands, Christopher lay under a sun shade and crawled out to the poolside under our watchful gaze. His third tooth arrived. We listened to the Beatles hit ‘I want to hold your hand’ which we remembered being played at Mailsi without knowing what group it was. I blistered my feet badly playing quoits barefoot on the hot steel deck. We played mindless games like Tombola and Housie-housie. We danced at evening parties and Cubby made children’s outfits for a fancy dress party – Nicky as a fairy, Karen as a pixie and Christopher as a strongman.

We stopped at Aden, near the mouth of the Red Sea, still a British Colony. Insurrection for independence had not yet started - all was quiet. The British only left in 1967. We brought a duty free ‘double 8mm’ cine camera and a heavy spool tape recorder from an Indian Shop Keeper imagining that they would be modern for years to come - the tape recorder soon became obsolete with the introduction of small audio cassettes playable on radios, and the home ‘cine camera’ was replaced rather later by video recorders.

We sailed through the straits ‘Bab el Mandeb’ at the mouth of the Red Sea passing Somaliland to port and up to the Gulf of Suez with the rocky coast of the Sinai Peninsula in view on starboard. At Suez many passengers took a day bus trip to Cairo, the Pyramids and nightclubs rejoining the ship at Port Said. We would have liked to do this, but there was no one with which to leave the children on board. The passage through the 100mile long Suez Canal was safely undertaken with Egyptian Pilots (despite the jingoistic reservations of the British and French when Colonel Nasser nationalised the canal in 1956). The inevitable gooly-gooly man came on board and entertained the children with his repertoire of magic tricks – conjuring small chickens from all parts of his voluminous coat. Hawkers also came on board but had scant success as passengers had already had a surfeit of bargaining in the east.

|

|

|

|

|

Freeze Frame pictures of Suez Canal extracted from home movie made with camera bought at Aden |

|

Three years later after the Arab Israeli Six-day war in 1967 the canal was closed until 1975, we were fortunate to have had the opportunity to sail through it.

We sailed on through the dull and overcast Mediterranean Sea, started putting on pullovers and partaking in warming Scottish dancing patriotically organised by ships officers. Two stowaways were found hidden in the ventilation cowlings on deck, and were locked up for the rest of the voyage.

An English novelist travelling on the boat organised a cocktail party in honour of the Nigerian High Commissioner to India and Pakistan who was on board. We were invited and sipped champagne while the High Commissioner remained unaware of our South African origins.

We went ashore at Gibraltar, shopped for clothes, saw the Barbary Apes on the rocky slopes, then headed through the Pillars of Hercules on to Liverpool.

At Liverpool the Customs Officer surprisingly wanted to levy duty on the few carpets, and oddments we had purchased, but on showing tickets through to Denmark he waived this. We continued by train to London and stayed a few days visiting friends. Then went on by overnight ferry from Harwich to Esbjerg and on to Cubby’s waiting family in Copenhagen.

Some months after our return Cubby’s article ‘Mailsi Fun’ together with her line sketches were published in Christiani and Nielsen house magazine ‘CN Post’ which has prompted many of the recollections in this chapter.

We heard a few years later after completion of the Qadirabad project that there had been 5 divorces in the expatriate community, some of them between friends we had known. We were pleased that we had not gone there after Mailsi.

[1] Body piercing (except for women’s earrings) only became popular in Europe at the end of the 20th century.

[2] Traditional tasty Danish open sandwiches

[3] The first and only time I came across my namesakes brew

[4] However, the dowry system persists in India and Pakistan and can lead to many problems for women and their parents.

[5] Two wheeled carts

[6] When I retired in my sixties, I went trekking in another part of Pakistan - in the Hindu Kush

index memoir - homepage - contact me at