index memoir - homepage - contact me at

We sailed from Cape Town on the Union Castle[1] Liner, Winchester Castle, travelling cabin class. Cubby, with flat stomach, was not yet visibly pregnant. Family and friends came aboard and bade farewell, then waved from the crowded Duncan Dock quay as we slipped away amidst streamers and sirens. Lion’s Head, Signal Hill, Table Mountain and Devil’s Peak covered with white tablecloth faded away; we little realised that it would be thirteen years before we returned.

In our two-berth cabin one bunk was above the other, an unfriendly configuration for a newly married couple. We could squeeze together briefly until the upraised wooden edge in my back forced me to the bunk above. Cubby’s father had paid her fare and I had borrowed about £150[2] from my father which covered my £90 fare for the 2 week voyage including all meals. The remaining £60 was for living and expenses until I started receiving a wage. I repaid this loan over the next 10 years.

We inched steadily up the west coast, the sea was flat like jelly, the gangways smelled of rotting onions, the cabin was hot, so we rigged up a deflector with a file cover and coat hanger to direct fresh air through the porthole. Out on deck passengers were bathed in sweat almost as if they had swum with their clothes on. Voyagers were both British, some with regional accents difficult to understand despite spending years in South Africa, and the rest South Africans of various colours, but Apartheid had happily ended at the quay.

|

|

|

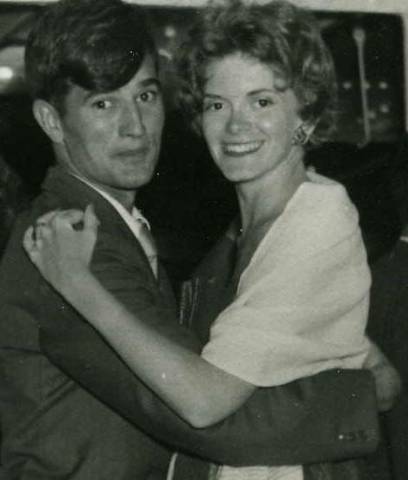

On Winchester Castle sailing from Cape Town to Southampton in 1959 - Cubby on deck chair, dancing, stop at Las Palmas |

||

Time whiled away with meals, raffles, deck games, bingo, and dances - every woman wanted a dance with a ship’s officer in a smart white uniform. We saw the film Separate Tables with Deborah Kerr, Rita Hayworth, Kirk Douglas and David Niven. It was a restful two weeks, compared to later jet planes supplanting passenger liners. Cubby commenced writing letters home to her parents and continued for forty years. They carefully filed them.

Approaching Las Palmas the sea became rougher. The Athlone Castle, travelling outward from England docked 5 hours late, a sign of the storms to come. In the harbour 3 miles from the town we saw several passenger liners and a flotilla of French warships sailing away with red pom-pom berets smartly lined up on the decks. We toured Las Palmas, sharing a taxi with two other couples all for 30 shillings. Scantily clad women and those wearing trousers were banned from entering the Catholic cathedral. The taxi driver, singing melodiously, accompanied himself drumming on the dashboard with both hands off the steering wheel. There seemed to be no stop signs at road junctions, the first to hoot had right of way. As a reminder that the Island was close to the Sahara desert, we hired and mounted camels and were photographed by our driver.

An anxiously awaited cable from my father informed that I had passed my supplementary survey examination - my Civil Engineering degree would be awarded mid year in absentia. At least I could now start work with a recognised degree.

Gales lashed the boat and seasick passengers confined themselves in their cabins while we strode around the heaving decks. Some passengers were briefly ill with what we thought was bad fish, and I, after drinking a bottled Oranjeboom beer rushed to our porthole to throw up. Cubby thankfully did not suffer from morning sickness.

We disembarked at cold and blustery Southampton and passed without a hitch through immigration, there were no entrance or work restrictions for Commonwealth citizens into Britain. The customs officials casually waved through our baggage, included three large wooden chests, without demanding that we open them for inspection – we obviously looked too naive to be smugglers. Mercia, Cubby’s mother had anticipated most of our future household needs, but the chests were heavy. I could not lift them on my own so we paid Cox and Kings to transfer them to London and then caught the boat train.

As we approached London in gloomy overcast weather we saw a back view of endless shabby brick terraced houses – a bit depressing, not what we were used to in South Africa.

After a few days at a hotel in St James at £2/10 shillings per night, we moved to a bed-sitter in St Johns Wood where we paid £4/10 per week. We fed countless coins into the gas meter - as thin-blooded South Africans we needed minimal warmth to survive an unaccustomed cold climate. We had some gas rings in the room together with a wash hand basin enabling us to do fairly basic cooking. The shared toilet and bathroom were three stories below. The Landlady reminded Cubby, unschooled in housekeeping, she should sweep and clean her room – brooms were available on each floor. We rapidly found a quick-wash[3] and learned how to use it. We bought a cheap radio set to which Cubby listened when knitting and sewing. In our unsettled situation television was not feasible.

I reported at Ove Arup and Partner’s[4] office, as had been pre-arranged from South Africa, and started work near Fitzroy Street, earning initially £450 per annum. I calculated reinforcement for multi-storied concrete buildings using methods learnt at university and made drawings[5] most of which had to be finished with black ink. About 300 people worked in Arup’s London offices at that time - many were engineers from abroad, some staying relatively short periods of 6 months to a year. Arup was expanding rapidly internationally, some of these engineers when back at their homes, started branch offices. Our section was managed by friendly Frank Coffin, and my other colleague were easy to get on with and helpful.

Cubby followed up possible work leads in the commercial art world but without success. She registered with a doctor who found a place for the delivery of her baby, expected in four months, at St Mary’s Hospital in posh[6] Hampstead. Later she attended ‘relaxation’ classes and ‘mother craft’ lectures at the hospital. She also received vouchers for cheaper milk, orange juice and vitamins. She would not qualify for the £10 ‘birth bonus’ as I would not have made sufficient national insurance contributions.

One of the first Sundays after our arrival we went to Putney Bridge to see the Oxford and Cambridge boat race. We glimpsed the start but chilly rain started falling and feeling cold we returned home and listened to a recording of the race.

Tiring of our single room, which would be too small with a baby, we eventually found a few furnished rooms for rent in a house on Church Crescent off Muswell Hill Road. This was owned by a crotchety old man, the ‘colonel’, as we nicknamed him, who wanted only respectable professional people, doctors or lawyers were preferred. Cubby said that ‘civil’ engineers[7] were also professionals, and mentioned that she was interested in Art. He then enthusiastically showed her his parlour cluttered with nude statues, brass sylphs and dancing Cupids - his inspiration for writing an intended opera. Despite Cubby now being visibly pregnant and we being foreigners, he surprisingly accepted us as tenants at £3/15 shillings a week with an extra £1 per month for gas and electricity. He was somewhat dubious whether his accommodation would be suitable for winter living.

|

|

|

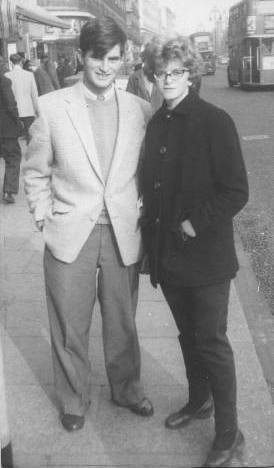

1st picture - In London - near Marble Arch. 2nd picture - At Leicester Square, Cubby with visiting Cape Town University friend Corder Tilney 3rd picture - Cubby knitting at Muswell Hill rooms for expected new baby. |

||

Susan and John Carter, a friendly young English couple, had also recently moved into the house. John, a doctor, was a junior Houseman[8], working long hours and sleeping short hours four nights a week at his hospital. Susan was also expecting her first child. We thus had mutual support against an idiosyncratic landlord.

Muswell Hill was a pleasant village with, fishmongers, greengrocers, grocers, and dairies. There was more human contact than in later over chilled and antiseptic supermarkets. We spent about £1 a week on our Saturday main shopping supplementing this with some purchases of perishables during the week - we had no refrigerator. As there was no bath, we warmed water on the gas rings each night and washed in a galvanised steel[9] basin placed on the floor.

During the week, I walked through Highgate Woods to catch the Northern Line ‘tube’ (underground railway). Smoking[10] was I think still permitted on the escalators, passageways and platforms at this time. Woodbines and Players appeared to be the cheapest cigarettes available, and could be purchased in packets of five – the occasional corner shop would sell them singly. The carriages[11] had long bench seats on either side and were crowded and I usually stood gripping a straphanger. Alighting at Goodge Street Station, just off Tottenham Court Road, I, in a crush of commuters, ascended slowly from the depths in a huge lift, then walked to close by Arup’s offices.

Every week Arup provided six luncheon vouchers, each worth half crown (12½ pence in today’s metric money). These easily covered the cost of meals at the numerous small restaurants scattered close to our offices where I ate with colleagues. We sometimes pooled our tickets and went as a large group to a Chinese restaurant ordering and sharing many dishes. Cubby often joined me at lunchtime in nearby Soho or occasionally we would buy delicious crisp rolls with ham or smoked salmon made by an elderly couple in a nearby terraced house. We ate them on a park bench amused by pale skinned workmen who stripped to the waist to catch the sun.

Everyone seemed to come to London. We met Cubby’s Danish relatives - the three Willert cousins – Mette, Hannah and Soren, also her godmother Gerda and her husband Knud Sorensen, he had been working in Cape Town as a Civil Engineer when Cubby was born. My uncle Jim Barker[12] and his wife Margaret came from Umtali, Southern Rhodesia.

We avoided Earls Court, a South African (and Australian) ghetto at that time – we wanted to meet new people and not wallow in nostalgic memories of South Africa.

With a South African colleague of Estonian descent, we sailed in sunny weather on a pleasure boat some hours up the River Thames to Hampton Court passing colourful houseboats at Chelsea and being impressed by the verdant green of the countryside. We picnicked, saw the famous ancient grape vine within its glasshouse but avoided the crowded maze. We returned back to London on a Green Line country bus. At a colleague’s party celebrating his marriage, a Greek Cypriot to a Swiss Wife, some Turkish Cypriots were also amicable guests despite the strife[13] on their Island at that time.

We dined with a Chinese engineer from British Guyana, he cooked the Chinese food himself.

We saw the Mouse Trap and attended a performance of Madame Butterfly, Cubby’s pregnant tummy managing to squeeze between the narrow steeply rising backstalls in the old Covent Garden Opera House. Corder Tilney on holiday in England asked us to the Palladium where Franki Vaughan kicked up a leg to girlish shrieks.

|

|

|

|

Nicholette born 8th July 1959 in London - pictures with Cubby in Muswell Hill rooms - with me in Highgate Woods - sunbathing at Muswell Hill Lido in Indian summer weather in late September. |

||

Baby daughters arrived at Muswell Hill, first Susie Jane to Susan, then Nicholette to Cubby on July 8th. At this time first children were invariably delivered at hospital and Cubby being slightly overdue had reported to St Marys to have it induced. After the birth mothers stayed in hospital for 10 days which was convenient for us not having the support of relations in London. At the hospital the matron ruled the roost and younger nurses seemed intimidated and jumped at her command – indeed Cubby, not yet 20 years old, found her unsympathetic and domineering during her delivery.

Both babies thrived while sleepless-nights, sterilising bottles, mid-night feeds and safety pinning nappies[14] changed our lives. Nicholette went with us everywhere in a carrycot[15]. In the glorious weather in October[16] we swam at the Highgate open-air pool proudly carrying our young infants. The end of this long hot Indian summer drew to a close, we coming from South Africa thought it a normal situation, subsequent summers disillusioned. Cubby had Nicholette christened at the local parish church – the pastor seemed initially reluctant to undertake this - we were not Christians of known local standing.

The drains blocked, our landlord demoted by us to ‘batman’, said there was no longer room at his abode, the Carters and Allsopps were forced to seek alternative accommodation. Both families moved together downmarket to more spacious rooms in Huddleston Road, Tufnell Park, close to Holloway goal, and home making started afresh. We had two rooms an enormously large bedroom on the ground floor and a basement living / kitchen room which could be heated by an open hearth fire[17]. Surprisingly a toilet had been built into the adjacent coalbunker. We also seldom used the communal bathroom, several storeys upstairs except for an occasional bath. Indeed a bullying tenant seemed to think, that as the longest resident, she had sole entitlement to it.

I now caught the tube for work at Kentish Town and we often shopped at Camden Market where I remember buying pork chops sliced with a portion of kidney – delicious grilled[18]. The stallholders mockingly called anyone without their local accent ‘squire’. The ‘class war’ was still very much alive. Susan invited us to Sunday roast dinners and introduced us to Brussels sprouts – for us an exotic food not available in South Africa. We also visited her hometown, Hertford and met her mother, a widow, Mrs Wren.

|

|

Cubby and Nicky at Tufnell Park |

We stayed at Tufnell Park until I left Ove Arup at end March 1960 to join a contractor[19] on a project near Doncaster in Yorkshire. On my Arup salary, even although it had increased to £660 per annum, we had felt trapped within London. Travelling to towns and countryside outside was both expensive and time consuming and owning a car in London was out of the question; we wished to see more of Britain.

During the year we had taken several train journeys – to Oxford to see Mette. I had gone to Bath on an Arup site visit prior to the rebuilding of the Grand Pump Room Hotel and had seen the Roman baths. I had also taken a trip to Glasgow for an unsuccessful job interview. Nationalised Railways were still an effective means of travel, only a comparatively short length of motorway[20] had been built and long distance car travel was not that common.

We left behind my sister Ruth who had been in London for some months starting on a years break from S A. She was teaching at a secondary modern school. John and Susan Carter soon moved to North Finchley where he became a General Practitioner – we kept in touch.

Prior to leaving Arup, pictures of the Sharpeville massacre on 21st March 1960 in South Africa by policemen of Africans protesting against the pass laws were spread across the front pages of newspapers. Things had deteriorated at home, we did not feel proud of being white South Africans, but our accents continued to identify us.

Years later I read with interest Australian Clive James’s amusing, and South African J M Coetzee’s depressing, memoirs describing their stays as bachelors in London about this era. I am thankful that I was married and was not alone in what can be a stimulating but also lonely city.

[1] Their ships were the ‘mail boats’ taking post between South Africa and Britain. Airmail was not yet commonly used and was more expensive – one posted early to meet Christmas deadlines.

[2] English and South African Pounds were equal value.

[3] These had not been available in South Africa when we left

[4] Founded after the 2nd World War in 1946 by Danish born Ove Arup

[5] Today forty years on most drawings are made on computers (CAD computer aided design) and drawing and printing skills have possibly declined.

[6] Word derived from voyages to India – Port Out, Starboard Home ensured that one was on the shady side of the boat

[7] ‘Engineers’ in Britain are thought by the general populous to be persons working with their hands, fitters or turners or nut and bolt tighteners. Electricians, motorcar mechanics, plumbers etc are also erroneously called engineers.

[8] Junior doctors were low paid and clearly exploited - this continued for many years

[9] Such basins were not yet available in plastic

[10] The Kings Cross fire disaster, caused by cigarettes setting wooden escalators alight, occurred decades later.

[11] The cross section of both tunnels and carriages were surprisingly small – probably to reduce construction costs

[12] see chapter on Relations describing our disastrous dinner party

[13] The northern part declared itself a separate Turkish Cypriot State in 1975

[14] Disposable nappies were not yet sold in England, we had to wash cloth ones. We could not afford a fetch and return nappy service.

[15] A light cot, with handles, placed in a collapsible, wheeled frame. Easy to use on Tubes and buses where large high sprung prams were impracticable especially on escalators.

[16] Over 40 years later this summer of 1959 is still on record as one of the best

[17] Smokeless fuel had to be used as Smog had killed any people about 10 years earlier.

[18] Later apparently for hygienic reasons legislation was passed requiring that kidneys be detached

[19] Contractors generally paid higher wages

[20] The M1motorway to the north of England.

index memoir - homepage - contact me at