index memoir - homepage - contact me at

Registration in the Engineering faculty of the University of Cape Town (UCT) was an informal procedure in 1955. Prospective students queued up and presented their school examination results to staff members who directly assessed them asking questions only in case of doubt. One potential student had poor mathematics results but I overheard him persuading the selectors that he was worthwhile giving a chance. Years later he became a professor in Civil Engineering at UCT

Among those registering was Peter Albert who had attended the ‘blue’ Pinelands Primary School with me but later had gone to Marist Brothers, a Catholic senior school in Rondebosch. Peter, a friendly tall and skinny youth, introduced me to many of his friends and indirectly to my future wife Cubby[1]. There were no women student taking Engineering in our year, it was very much a male preserve, but we attended common lectures in Physics, Chemistry and Mathematics and both sexes sat together chatting on the cold stone benches in the sun in front of Jamieson Hall between lectures. Stirred by the proximity of the fair sex, I started writing bad poetry.

At this time as many people as possible seem to have been given the opportunity to start studies and then sank or swam on their own efforts. The brightest students at school did not necessarily succeed – perseverance seemed an important factor. With about 150 students commencing Engineering[2] studies only about 50 would pass into their second year. The rest repeated subjects, dropped out, or moved to less demanding faculties. The maths, physics and chemistry I had taken at school had been to an advanced level and this, with studious application, enabled me to pass the first year despite the other distractions of student life. The following three years of this four year course proved more demanding.

I continued living at home and went by bus or got a lift to Mowbray with Dave Goldschmidt, our neighbour, and then walked about 20 minutes up the hill past Mostert’s Mill, and along de Waal’s Drive to the University. Students from other parts of South Africa and some from Rhodesia stayed in University halls or in private digs. A few students drove cars[3], motorbikes, and Italian Vespa and Lambretta scooters but most walked, hitchhiked or took public transport. In our first year as ‘Freshers’ we wore a yellow tie, but were not subject to any hazing by older students.

The university Freshers’ Ball was held Jamieson Hall and some young men demonstrated their ‘virility’ by drinking too much alcohol, puking unpleasantly in lavatories and elsewhere. Some became dangerous throwing empty beer bottles at persons passing by outside.

When I started at UCT it was still open to all races, the only apparent selection criteria being academic ability and funds to pay the fees. There were very few Coloured, African or Indian students and these tended to be in the arts and law faculties and not in science and engineering. Factors such as inferior segregated schooling, much lower incomes than whites, restricted movement and practical difficulties of distance from the university made attendance at university all but impossible except for a small number.

During my period at UCT, the Apartheid nationalist government, despite protests and marches by staff[4] and students past the Parliament buildings in the City Centre, legislated the separation of races at universities thus reducing still further potential contact and dialogue between races or indeed future leaders in the country. Although many students supported the principle of ‘open’[5] universities, some students abstained from such marches not necessary on principle only, but in fear that their bursaries would be withdrawn or they would later suffer discrimination if they should seek a government job.

In the 1990’s the situation at UCT and other universities reverted to ‘open’ status. With increasing numbers of students of all races, students and staff learning to work and study together was apparently not a frictionless process.

Rather than studying purely for the sake of knowledge, the object for the majority of students in my time had become the gaining of skills to provide us with a livelihood. Studying Civil Engineering fitted into this category and gave me some interesting technical and practical problems, and the opportunity to travel.

Lectures at UCT were, with a few exceptions, not presented in an inspiring manner. Copying notes written on the board by a professor or lecturer trying to complete the syllabus is not stimulating or the best way to learn. It ensured that you attended lectures - copying notes by hand from another student later on was tiresome. Even before 1970’s, when photocopying became common, notes could have been roneo-ed off and given to us. Lecturers could have concentrated on teaching the principles and facts with more student participation.

Professor James, however, a short white-haired professor well past retirement age, enthusiastically gave first year physics lectures to about 400 students in the New Science Lecture Theatre. Only 30 years later when I read Shackleton’s book on his adventures in the Antarctic did I realise that he was the young scientist in the party. He had survived the terrible hardships of that amazing expedition after their ship Endurance had sunk.

With the pressure of revising for many year end examinations, I usually fell short on some subjects and knew beforehand which ones I was likely to fail. Fortunately we could write supplementary exams before the next years lectures commenced. The second time round, with more time for revision, I usually passed satisfactorily. I finally concluded my studies without exceeding the 4year course duration. A system of staggered exams throughout the year would be a more realistic principle to ease the burden of revision.

The subject Land Surveying had been a stumbling block for me in my final year. Although the theory and field work with theodolites and levels was interesting and gave us a chance to get outdoors, precise calculations were extremely boring and time consuming.

Trigonometric functions of angles had to be tediously looked up in logarithmic tables or Facit[6] calculators used. In my final year I failed my survey exam but fortunately passed the supplementary.

|

|

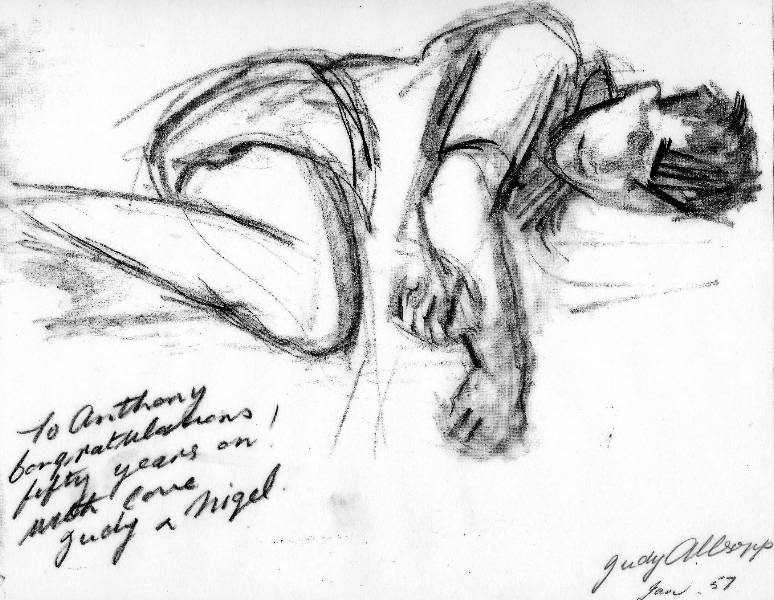

Sketch of me at 20 years while at UCT - by my sister - given to me on my 70th birthday |

| |

| Picture of the UCT Civil Engineering Class of 1958 |

During winter in my first year at UCT I joined the rugby club, and started playing in the under 19year section. I found I could only get a place in the 4th or 5th team. I now realise, that although I could accelerate rapidly over the first 10meters, thereafter I was too slow and too easily caught and tackled by my opponents. Disappointed, but still wishing to play competitively, I with several other student players joined a pleasant club, Villagers, in Claremont with good camaraderie and played in their under 19 C team.

This did not last long. In one match[7], a large opposition forward, breaking through a line out, grabbed me by the collar and flung me through the air while I clutched the ball under my right arm. I landed with my left arm outstretched and with the momentum rolled over it, dislocating my elbow. This was a dangerous high tackle but would not have incurred a penalty under the rules of the game at that time.

St. John’s Ambulance Brigade voluntary personnel, who gave first aid at most games, immobilised my arm and took me to a nearby doctor’s surgery. He took me to Wynberg Hospital where several attempts under nitrous oxide (laughing gas) were made to tug my arm and relocate the joint. I woke, between attempts, stupidly amused until it was ultimately put back – no bones had been broken.

My elbow was a swollen mass of purple into which I could push thumb craters which then gradually dissipated. My only subject affected was technical drawing - I could not hold a Tee-square. As the swelling subsided I started squeezing and bouncing a tennis ball taking about 3 months to recover. Fortunately it has given no trouble since.

|

|

Picture showing rugby players from several engineering years - I am on left front |

Other pastimes such as mountain and rock climbing soon gripped my attention, but I turned out for our engineering year’s rugby side. Making a tackle, I was kicked on the head and taken unconscious off the field to hospital by a friend[8] – awakening and puking through his car window on the way there.

At the end of my first year I found a vacation job at a cement plant at De Hoek near Piketberg. I travelled the 120km from Cape Town by Railway Bus, but later hitch hiked to and fro. The journey north passed dorps Malmesbury[9] and Moorreesburg and crossed the Groot Berg Rivier. It took about 3 hours as the road followed the twists and turns of numerous hills.

The factory and quarry had it’s own village with bungalows for ‘white’ married staff and also a club, bar, swimming pool, tennis courts, and a nine hole golf course – distractions to keep staff content in this backwater. I stayed at the bachelors’ mess with Johan, a law student, at Stellenbosch University (the oldest Afrikaans University in South Africa).

One day Johan surprised me at breakfast barking at the African waiter that he did not eat ‘Kaffir food’ and demanding that the ‘mielie pap’ (maize porridge) in front of him be removed. This was unacceptable racism at first hand.

Despite the large Coloured[10] population in the Cape with many impoverish and unemployed, a cheaper African labour force was employed on the cement plant. They were housed in dormitory barracks in a separate compound. They were recruited from the ‘reserves’ in the Eastern Cape for a year, leaving wives and families behind to which they would later return.

My duties were clerical determining labourer’s wages to be paid weekly in cash. Only one calculating machine was available in the office and was hogged by more senior staff. Money (shillings, pence and farthings) and hours and ¼ hours, had first to be converted to the decimal system, and then after doing the sums converting back again to pounds, shillings and pence. I did these tedious calculations[11] either mentally or manually in a rush to meet pay deadlines. I often woke at night still doing sums in my dreams.

Outside work activities compensated for the office tedium. At midweek parties at the club I danced passionately with an attractive, shapely, olive skinned Afrikaans girl Liffie who lived in Piketburg. We communicated verbally hardly at all, she spoke no English and I little Afrikaans. On most weekends I hared back to Cape Town to see another girl, a fellow student who lived at Kalk Bay in a house over looking the sea but my passion was not reciprocated and the relationship ceased when University restarted. I regretted not spending my weekends in Piketberg with tanned Liffie[12] in her yellow Bikini at the poolside. Liffie became a student at Stellenbosch University and we did not meet again.

From our living quarters we saw a valley of rolling golden wheat fields and the Kouebokkeveldberge[13] standing 5000ft high blue in the east. These mountains are the source of the Olifantsrivier[14] flowing northward past Citrusdal, past the Cederberg, through the Clanwilliam dam and turning further on into the cold Atlantic Ocean.

My first climbing trip with the UCT Mountain and Ski Club to the magical Cederberg area was made the next year. Later, on my return to South Africa, between 1972 to 1980, we frequently drove up to the Cederberg for camping and walking holidays dragging our five obdurate children along on walks in the mountains and swims in river pools.

The University of Cape Town lies on the eastern slopes of Devils Peak[15]. It is built on the estate of Cecil Rhodes, both the founder of Rhodesia and one time Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. From the granite steps of the University’s Jamieson Hall the suburbs of Cape Town stretch out across the Cape Flats towards the wine lands and the mountains barring the hinterland. These mountains are clad on occasion with snow and look enticing on a crisp, cold, sunny winters day. Few, if any, other universities in the world have comparable views.

It was towards these mountains, I with some of my fellow university students, journeyed. We hitchhiked through the country towns of Paarl and Wellington and crossed the narrow winding Bains Kloof Pass. The pass had been blasted from rock right on the edge of a precipitous ravine above the river gleaming far below. At the end of the pass we turned left towards Ceres. Starting up Mitchell’s Pass, we stopped where the Wit Els Kloof[16] joins the Dwars Rivier the starting point of our hike[17].

We were about 10 in number and commenced hiking up the Wit Els ravine, following paths on the edge where they existed in the early stages, or boulder hopping where there were none. Occasional missteps and ducking in the stream were a relief for us sunburnt hikers carrying heavy backpacks. The water, as in most Cape mountain streams was sparkling clean, and we drank dipping cupped hands, or flopped outstretched and sucked direct face under water. We trudged through the mountains, deserted except for wild animals, stopping only for meals or for the night. The evening meal invariably comprised tinned pilchards[18] in tomato sauce bought by our leader Georges Delpierre as it was one of the cheapest foods – we groaned when we ate it yet again.

At night we sat around a fire and slept under clear starry skies. We often awoke on deflated airbeds with rounded pebbles boring into us. At daylight, while we preparing breakfast, baboons, higher up the ravine sides caught the morning sun before us, and copulated – the dominant males mounting complacent females, and at the climatic moment rendering the air with cries of ‘boc-um’.

After about three days of hiking upstream the valley sides closed in even more tightly, forming deep vertically sided river pools. We opened our packs, blew up airbeds, stripped[19] and swam pushing our gear floating in front of us in the icy cold water - cold despite the sun overhead during the day. We crossed about three pools then reached and skirted round small waterfalls. Near the top of the kloof, we scrambled up steep sloping rock slabs out of the ravine to reach the Universities Mountain Hut some way below Waaihoek[20] peak. Ski enthusiasts used this hut mainly in winter if sufficient snow fell.

After a night’s rest we descended in fine weather by the more normal route towards Waaihoek farm[21] on the Worcester side. I recalled that my Rondebosch High School teacher Steyn Krige had told us in class how a skiing party had deviated from this route in snowy and icy conditions and several had perished falling down precipitous gullies.

Another trip up Waaihoek in 1956 with a group of fellow students

After our 60th year Rondebosch High School reunion in March 2014 Georges Delpierre kindly sent me the photograph below which he had taken on another UCT trip up Waaihoek in 1956

|

|

| from left - Murray Boyes, Wade?, Boydell, Cynthia Grindley, Derek Hudson, me -Tony Allsopp, Allan Hudson, Tony Cartwright |

Before one university long summer break, Corder Tilney a fellow Civil Engineering student asked me to accompany him to assist some farmer friends, Bill and Beth Bramley harvesting wheat in the Free State. Corder one of two twin boys (his brother Barry) was slightly older than me and had attended the same school. He had grown up in a rural Cape country town and was perfectly bilingual in both English and Afrikaans – his mother was an Afrikaner and his deceased father English.

We hitchhiked from Cape Town. Lifts faltered after 300miles in the dry semi desert Karroo plateaux at ‘Three Sisters’ - three nearby kopies. We spent the night on the side of the road in an open bus shelter. The stillness of the night was occasionally broken by traffic approaching at speed with a roar and whooshing past. Our probably invisible thumbs were ignored - no one stopped.

In daylight we were more successful and got a lift. On entering the Free State our driver stopped at a dorp café. Heavily bedecked sticky flypapers coiled down from the ceiling, but we enjoyed surprisingly good coffee and delicious sandwiches. At Senekal we contacted our hosts who fetched us back to their farm.

Our farmer hosts were English speaking in The Orange Free State[22], a predominately Afrikaans speaking province, but spoke Afrikaans well. Their Basuto farm labourers also spoke Afrikaans and no English. Farms in the Free State are large and widely spread, but still seem dwarfed by the immensity of the vast blue sky with patches of changing white clouds.

The wheat was ripening yellow ready for harvesting. Bill had two combined harvesters and we set to work. The machines had competent Basuto drivers and our role was to see that the accompanying teams stuck to the task of collecting and loading the filled bags of grain and to resolve any difficulties such as equipment breakdowns. Occasionally a wild hare would break cover and the tedium of harvesting was relieved by the following chase by farm labourers - with a kill for the pot if they were lucky.

Every day my skin burnt red in the sun, but turned brown over well-slept nights ready for the next day. We enjoyed sheep’s trotters prepared by Beth, something I as a city dweller had not eaten before.

Bill also contracted to harvest on other farms and he and Corder left for some days while I continued on my own. The feeder in front of my harvester hit an earth bank and a folded metal joist buckled below putting the tray out of horizontal. Working in the confined space under the feeder we managed to straighten and strengthen the joist by laboriously drilling holes by hand and bolting on a gusset plate. Harvesting recommenced.

On rest days we tried hunting wild birds with a .22 rifle, not quite the right thing for this type of game but giving it more chance than a shotgun. We returned empty handed.

I went harvesting alone to a small neighbouring farm for a few days. The farmer, a widower, and his two daughters about my age lived in fairly basic conditions compared to Bill’s farmhouse equipped with most modern conveniences. They had no electricity or plumbed in water. It seemed a lonely and primitive life, not all white farmers in South Africa were wealthy.

I went horse riding for the first time. No saddles were available, the Basuto labourers rode bare backed on their docile mounts and I followed suit managing not to fall off. Wearing shorts, I suffered for days from the chaffing on my thighs – short hairs had pulled out and become inflamed.

Before returning to Cape Town we both had small pox inoculations - there was a scare about. On the journey back Corder became feverish and we stayed in a hotel overnight where he fortunately recovered allowing our journey to continue the next day.

During one vacation at university I attended army ‘boot camp’. I had reached 18 years and been balloted for the ‘Active Citizen Force’[23], and attended for medical examination. We recruits, restricted to the ‘white’ population group, were examined perfunctorily at the ‘Old Drill Hall’ in Salt River near Cape Town. A series of training camps each year for the following four years had to be attended. After this we would be placed on the reserve list liable for call up in case of wars or emergencies, but would also have to attend further periodic short training camps. The memory of the second world war, concluded 10 years earlier, where South African volunteers as loyal British Dominion subjects had served and died, was still fresh in mind.

My boot camp was held for 6 weeks at Potchestroom, a small Transvaal town with an Afrikaans university specialising in theology for the ‘reformed’ Afrikaans churches. At that time these churches justified Apartheid on Old Testament biblical grounds.

I had been assigned to the ’46 Survey Squadron’ - composed mainly of university students studying engineering at English speaking universities throughout the country. We dressed in civilian clothes caught a steam train at Cape Town station and took two nights to reach our destination. We were placed under the control of ‘Permanent Force’ (P.F) non commissioned officers of the S A Defence Force. They had the responsibility for our basic training as ‘sappers’.

There was nothing scientific or intellectual about such training which concentrated on parade ground drill, smartness of dress, cleanliness of barracks, and physical fitness. Trainees who did not obey instructions or did not conform to required standards were subjected to ‘pack drill’ which involved several hours ‘marching at the double’ with heavy webbed rucksacks and rifles. This was distinctly unpleasant in the hot sun and I avoided it by not stepping out of line.

The training has both positive and negative aspects – it matured recruits and made them work as a team. It also tried to impose a group mentality where obedience to orders could become more important than moral beliefs or codes.

We pondered whether our coffee was being dosed with Copper Sulphate reputed to reduce one’s libido? One trainee nicknamed ‘blue balls’ when challenged in bed by other Sappers that he was ‘wanking’ said ‘yes and what am I expected to do when away from my girl friend’

The PF instructors were mainly Afrikaners and strong supporters of the Nationalist party. My friend Oliver Purcell put it to one of the instructors that the policies of ‘wit baaskap’[24] and ‘bantustans’[25] were bound to fail in the long run as blacks could not be indefinitely repressed. This instructor, as indeed most whites, after 300 years of settlement in SA, still saw themselves as being under threat by hostile natives[26].

We returned physically fit to Cape Town kitted out in khaki uniforms, with bolt-actioned .303 rifles from the First World War, but without ammunition. I left the rifle lying in my unlocked cupboard at home.

Our next annual training camp was at Pretoria’s ‘Voortrekker Hoogte’, for political reasons it had recently been renamed by the Nationalist Government from ‘Robert’s Heights’ (after the general in charge of British forces in the Boer war).

My friend Oliver’s rifle was stolen from the train compartment as he was hanging out of the window at Cape Town station kissing Jean, his future wife, goodbye. After months of interrogation, the rifle was not recovered. The police put it to Oliver that he had given it to his girlfriend as a souvenir. Fortunately the security situation within S A was still fairly calm at this time. Sharpeville’s massacre and other horrors were still in the future.

This camp was more relaxed than the first one where we had been confined within the camp for the first four weeks. It was easy to obtain passes to the town, but despite this many trainees took additional illicit leave dressed in ‘mufti’ several evenings a week to sample the limited joys of the town. I gave the Voortrekker Monument, looking like a gigantic wireless set from the 1920’s, a miss. We learnt to drive 3 and 5ton trucks, battered relics from the Second World War. We received some instruction in surveying related to targeting and firing 25 pounder guns. We fired our .303 rifles on a range – nothing very exciting – parade drill also continued but less intensely.

In the winter cold I suffered from toothache and reported to the army dentist. He apparently knew of no other treatment for a molar with a minor cavity other than extraction. After local injections he tugged at the tooth with his pliers - to no avail - it would not budge. Finally the crown snapped off and he picked up his hammer and chisel and broke out the rest in chips. He gave me a few painkillers and I reported back for duty[27]. My appetite undiminished, I ate lunch in the mess.

By evening I was feverish and reported sick and was sent directly to the camp hospital where I was given an antibiotic injection, and stayed overnight as the only patient in a 30 bed ward. Restored I returned fit the next day to duty.

That weekend I accompanied Oliver on a visit to his uncle who was manager of the Premier Diamond Mine near Pretoria and still feeling some pain was introduced to the medicinal powers of whisky for the first time.

On a free Sunday, I spent an afternoon away from the camp with three students from Witwatersrand University climbing quartzite rock pitches in the Magaliesberg near Pretoria. We then decided, as there was some time available after the camp before the commencement of the university term, to go on a trip to the Drakensberg Mountains in Natal. My climbing equipment, including my steel framed, leather strapped Bergan rucksack, was sent up from Cape Town by express post and we travelled to Johannesburg to get the rest of the parties gear.

Passing through Johannesburg to MacKay’s house (the only companion’s name I recall), I saw a park with a pond and rowboats and a pavilion looking vaguely familiar. I suddenly recognised Zoo Lake, I had last seen when I was 4 years old. My grandfather had been dressed in white and had been playing lawn bowls while trams (now replaced by buses) were travelling in the road. I had also ridden on an elephant.

We left Johannesburg and hitchhiked via Ladysmith before turning towards the Royal Natal National Park below the summit of Monte aux Sources. This peak at nearly 11.000 feet was the target of our trip. Towards Bergville lifts ran out and we continued on foot for about three hours and pitched camp in the dark off the edge of the gravel road. After dosing myself with aspirin to relieve lingering tooth extraction pangs, I slept soundly. We awoke to find we were lying on wet boggy ground, and hastened to breakfast at the Park camp - closer than we thought and then rested for the day.

The next day we slowly ascended following a water stream, and in the late afternoon found a cave where we ate and spent the night. After breakfast we entered a gully, our chosen route which none of our party had climbed before. We climbed a short not too difficult rock band using ropes and reached a steep gully covered in snow - it had fallen some days earlier. None of us had climbed in snow before. We found that we could laboriously kick steps bearing one's weight without crumbling as we balanced with our arms. We ascended about one thousand feet as if climbing a long stepladder. Fortunately the kicking action prevented my feet, which were in leaky tyre-sole boots[28], from freezing. We arrived tired and content at the hut near the snow-clad summit of Mont-Aux- Sources. After a night’s rest we spent a day ploughing thigh-deep through snow on the flattish top area. We descended using the more normal route to the Park Headquarters in 5 to 6 hours without stopping.

I was not successful hitchhiking alone back to Cape Town, lifts ran out in the barren Karroo at Beaufort West. As I had insufficient money for a hotel, I spent the bitterly cold night in the warmth of a heated railway station waiting room. A station guard turned out my companions, tramps sharing the warmth, at three o’clock in the morning. Fortunately I still had a valid unused army train ticket from Pretoria to Cape Town and this assured that I stayed warm until catching a train 260 miles to Cape Town in the morning.

Due to my final year’s university studies I obtained deferment from the next army camp, and after examinations left South Africa[29] in 1959 before the following camp came round.

Before a Civil Engineering degree could be obtained from UCT, students had to spend some months engaged in practical engineering design or fieldwork. At the end of my third year, through the agency of a local consulting engineer, I obtained a position in the not yet independent protectorate of Swaziland with the British Colonial Administration’s Public Works Department. Swaziland is surrounded on three sides by South Africa and on the east side by Mozambique, then a Portuguese colony but later to become independent.

Another younger student Peter de Villiers, who had also attended Rondebosch Boy’s High, had also been employed. We left Cape Town by steam train in December 1957 and travelled via Johannesburg to Ermelo in the Eastern Transvaal. The last 70 odd miles to the main town Mbabane was covered by bus. No passports were required to cross from South Africa to Swaziland at that time.

We reported to the Public Works Department and were assigned to assist their chief surveyor Bill Tatham. For the first weeks we were based in Mbabane itself taking ground cross-sections along the centreline of a projected new road linking Mbabane to South Africa. We plotted the cross sections and calculated the volumes of ‘cut’ and ‘fill’ materials required for the building of the road.

We lived in a caravan, and did our food shopping in the shabby trading stores and un-refrigerated butcher shops usually swarming in flies. Fortunately we did not have to do all of our own cooking as the local colonial service expatriates, both British and South African, often entertained us with meals.

We watched Bill Tatham, using tachometric survey techniques, mapping part of an area proposed for irrigation canals to be fed by the Usutu River. He had about eight Swazi men who he directed by battery operated loud hailer to the various positions he wanted plotted. Here they held their levelling staffs while he sighted his theodolite, took readings and simultaneously dictated the readings and description of the features to his recording clerk. Later he would calculate the levels and distances.

Today this sort of operation would probably incorporate the use of an electronic distance measurer but would be essentially similar. I did not see this system used later in Europe as one assistant to hold levelling staffs was expensive – let alone eight[30].

We were allocated a crew of Swazi assistants, and a Landrover and moved with our caravan from the higher cooler ground of Mbabane down halfway towards Bremmersdorp (now called Manzini). Bremmersdorp was even smaller than Mbabane and was at a lower altitude and thus warmer, indeed sub tropical.

We started investigating the sub soil conditions at regular intervals along the proposed canal line using a Williamson probe. This was a simple device consisting of screwed rods with couplings which where driven into the earth with the numbers of blows per foot recorded until refusal was reached. This piece of equipment could give results open to several interpretations, particularly if boulders were mistaken for bedrock.

When passing from survey point to survey point through long grass. Our Swazi assistants let us lead the way, apparently not through politeness as we were in poisonous Black Mamba snake country. Puffadders, also in this area, are probably more dangerous as they do not move out of the way and are more likely to be trodden on.

There were a number of farms owned and managed by whites at this time. We met two daughters of a Danish farmer and celebrated the new-year by dancing, relaxing at midnight in natural hot springs in a riverbed, and then cooling down in the farmer’s swimming pool, drinking beer at sunrise before retiring to bed.

It had just stopped raining before we started moving our caravan to a new site. We had hired a tractor and driver from a local farmer as this was more effective than our Landrover over rough ground. The tractor travelled barely 100 yards when the caravan became unhitched rolling undamaged to a halt. Despite our hooting and shouting the tractor driver continued on without looking back and apparently deaf to our cries. We gave chase in our Landrover, but although a 4wheel drive, this still slithered from side to side on the black greasy earth road while the tractor receded and finally disappeared in the distance. No explanation seemed possible for the tractor driver’s action – how could he not realise that he had lost his load? We could only ruefully laugh at this strange event.

Swazi King[31] Sobhuza II, king since 1921, gave a celebration party when he had been 36 years on the throne. When he died 25 years later in 1982 he had ruled 61years – close to Queen Victoria’s 64 years. At this party there was dancing by hundreds of bare breasted nubile Swazi maidens. They were dressed only in colourful low slung bands of beads well before miniskirts became popular in England in the sixties and before topless bathing started on the Cote Azur in the seventies. The British Commissioner was in attendance dressed in white and braid with a plumed hat sitting on a chair like a music hall act. He bent forward to sip traditional Swazi beer from the common container from which the chiefs and headmen had already drunk.

We returned to our less exotic lives in Cape Town where I found my girl friend Cubby in bed recovering from encephalitis[32] at her home in Camp Ground Road in Rondebosch.

[1] Peter press ganged his male friends to a party given by Marcella an Art School classmate of Cubby’s

[2] Civil, mechanical, electrical, and chemical

[3] Parking on campus was not the problem it was later to be become

[4] I recall Professor Pollard, who took us for Applied Maths, at the forefront

[5] Open to all races. Later those, who were not ‘white’, and could not find subjects taught in their ‘own race group’ university (which Were few in number) could if accepted attend one of the ‘white’ universities. This applied to a very small number including my son in law Ed February (the well known rock climber), who later in the 1980’s attended UCT studying archaeology. My daughter Nicholette was then accumulating botany degrees. Despite apartheid legislation not permitting persons of different races to live together, their relationship as students was possible in the area of Cape Town. It would have been difficult in many other South African districts where the police and neighbours were more intrusive.

[6] A mechanical computer with a handle turned for each digit. Today with electronic calculators, or with calculators built into theodolites, the calculation process is almost instantaneous. There is no longer a need for surveyors to spend their nights in tents calculating by candlelight. The slide rule beloved of engineers has also all but disappeared.

[7] Years later I heard of the talented Springbok threequarter, John Gainsford, and recalled that he had played with me in the same lowly team on that day.

[8] This friend was a Greek, older than most students, as he had worked underground in the Witwatersrand gold mines before coming to UCT. His family farmed near Paarl and cultivated Olives – not then a common crop.

[9] In South Africa names such as Malmesbury, Worcester, Elgin and Wellington, were thought by many as being Afrikaans as their inhabitants were Afrikaners in the midst of farming communities. Only later did I realise that such names were English in origin.

[10] White bosses often regarded Coloureds as being unreliable. Also alcohol addiction had been nurtured over centuries by Afrikaner farmers who used the feudal ‘tot’ system (dispensing wine) as part of wages to their coloured labour. The Coloureds also often showed an independence of spirit and sometimes a sense of humour not accepted by their sometimes dour or Calvanistic employers.

[11] The metric Rand introduced later in 1961 no doubt made calculations easier and faster.

[12] Liffie’s father was evidently called ‘Blackie’ because of his dark complexion. Her mother was French.

[13] cold deer terrain mountains

[14] elephants no longer roam here

[15] linked to Table Mountain

[16] White Alder Ravine

[17] I had camped during a damp Easter Weekend at the confluence of these two streams when a younger Boy Scout, but despite the magnificent unspoiled surroundings, had not enjoyed myself. The bullying attitude of older scouts and the endless washing of porridge dixies for about 30 boys with only sand as a scrubbing medium in icy cold river water had not been particularly enjoyable.

[18] Glenryke Pilchards caught and canned on the south west coast of Africa. These are still sold in the year 2000 in Britain.

[19] Rubber wet suits would have been useful but were not available at this time

[20] Windy corner

[21] About 24 years later at the end of 1979 before going abroad again, I repeated this trip in the other direction accompanied by Kobus Kriel (a friend also on the construction of Koeberg Nuclear Power Plant). My eldest son, 15year old Christopher, in his penultimate school year at South African College School in Newlands came with us. This time swimming was even more difficult, I dropped my pack from the airbed into the water and in numbed panic clung to the airbed. Fortunately the pack floated and was rescued by Kobus. Kobus and Christopher being more competent swimmers had no problems.

[22] Parts of the Free State had once been part of Lesotho (previously called Basutoland)

[23] The Apartheid Government later changed this system – draftees then became liable for a continuous two year service. Recruits, including many unwilling ones, were then used by the Government to enforce law and order among ‘blacks’ when ‘unrest’ had arisen or been provoked in black townships. These recruits were also employed in dubious covert wars in South West Africa (now Namibia) and Angola apparently to preserve ‘white South Africa’ in the long term. Unsurprisingly many youths became conscientious objectors or arranged their departure from South Africa. Fortunately all this was after my time in the Citizen Force.

[24] white supremacy

[25] Separate ‘independent’ black states within South Africa’s borders

[26] ‘white’ attitudes did eventually change. In 1990’s a referendum, restricted to the ‘white’ population, voted for an integrated society.

[27] About 40 years later when undergoing a wrap-round x ray at the dentist in England I was informed that some roots of this molar were still embedded in my gum, but should be left as they were causing no problem.

[28] Boots apparently made in Wurppetal Cape, with leather uppers but with soles cut from old tyres, surprisingly comfortable and cheap

[29] Sapper Allsopp returned to Cape Town 13 years later to find that his kit and rifle had been collected from his parents home and that honourable discharge papers had been received in his absence.

[30] Aerial surveying is now generally used where feasible for large areas rather than such instruments and survey control beacons are often now redundant.

[31] Swaziland in 2003 still has a king, who though university educated in England, has, in the style of his forefathers, taken many wives. Democracy is slow in being adopted and the king is extremely wealthy with many poverty stricken subjects.

[32] or meningitis - an inflammation of the membrane surrounding the brain - often fatal if not diagnosed and treated rapidly.

index memoir - homepage - contact me at