index memoir - homepage - contact me at

Schooldays are often put forward as being the happiest days of ones life. While I enjoyed my time at school, I do not see it in some nostalgic golden time warp, it was a ‘rite of passage’ to which I would not wish to return. We pupils were part of a controlled community, generally conservative and often unadventurous. We were immature easily influenced, and sometimes not discerning in friendships. Possibly my appreciation of the good schools I attended is somewhat clouded by them being restricted schools only open to privileged whites usually unthinking of such opportunities being unavailable to other South African races.

Before starting at primary school my mother sent me to an infants’ school run for a handful of children at a private home. Apparently I did not enjoy it and decamped walking the ¾ of a mile home alone and stubbornly refusing to return.

In 1944 when I was 6½ years old, quite late due to birthday entry regulations I joined my two sisters Ruth and Judy at Pinelands Primary School[1]. After my first year I was pushed up two, rather than one, standards becoming slightly young for my class. I had no problems catching up my classmates, as I had become an avid reader of books loaned from the nearby municipal library. There was no television in those days to distract me from Captain Biggles, The Hardy Boys and Just William.

The school was nestled in pine trees about 15 minutes walk from home across the local cricket fields and the main road, Forest Drive. Taking children to school by car was not an option, many families had no cars and mothers with second cars were virtually unknown.

This school with instruction in English was for both boys and girls. Some schools in other suburbs catered for the fewer numbers of Afrikaners in the peninsula. Strangely, the headmaster was an Afrikaner nicknamed Padda[2] because of his facial appearance. Several pupils had Afrikaans names such as Botha or Grimbeeck, but used English as their home language. Marriages between Afrikaners and English speaking South Africans were common despite reputed antipathy. To many rural Afrikaners ‘die Engelse’ were any ‘white’ who spoke English no matter how remote their attachment to Britain or how broad their South African accent.

Coloureds, who mainly spoke Afrikaans, attended segregated schools usually in areas where they lived. These had poorer Government provided resources than in ‘white’ schools.

African men in the Cape at that time were recruited as contract labour and if married left their wives and children at their tribal homes. They were not allowed to be permanently resident and had to carry ‘passes’ authorising their temporary residence. They were housed in special dormitory[3] compounds like Langa on the borders of Pinelands. Schooling for Africans in Cape Town thus in theory did not arise but gradually women and families came and settled ‘illegally’ in shacks they built mainly from corrugated iron.

Elsewhere in the country a minority of Africans children were taught at Christian mission schools. Africans such as Nelson Mandela had attended such schools. Such schools effectively disappeared when the Nationalists introduced their Bantu Education Act in 1953 promoting an inferior standard of African education. At these ‘bantu’ schools Afrikaans was a compulsory subject. In 1976 African pupils rebelled against learning Afrikaans, the language of their perceived oppressors. This can be pinpointed as the start of the end of Apartheid.

With segregation of children at schools and social segregation of adults, there was little knowledge of other cultures living in the same country. Stereotyped prejudices were common and did not immediately disappear once Apartheid was finally abandoned.

Primary school flashed past without any particular problems or highlights. I remember once being caned on my hand for getting something wrong, but was not particularly traumatised. Occasionally a farmer sold grapes at the school for 2 old pennies per pound - very cheap (South African Pounds were on par with British ones – the introduction of the Rand at two Rand per pound was only to come in 1961 when South Africa left the Commonwealth).

As there were no senior schools in Pinelands at that time, Ruth when she had passed standard five commuted daily a considerable distance by bus and train to Wynberg Girls High School[4] (WGHS).

Judy later went to the closer by Rustenberg G H School in Rondebosch. Separate senior schools for English Medium instruction were generally provided for each sex at that time but this was later to change. In 1950 I went to Rondebosch Boy’s High School, another white government school, in a middle class suburb of that name closer to Table Mountain. While not fee paying some contribution was required each term for development of buildings and facilities. Sums raised were matched in equal measure by the Cape Educational Department. About 600 boys attended the school and about 8 playing fields were used for rugby and cricket - rather more than in the average school. A large tiered assembly hall / theatre and swimming pool was added in my time.

I cycled about 3 miles to school each day passing the Mowbray and Rondebosch Golf Clubs separated by the smelly Black River and then the umbrella pine fringed Rondebosch Common - grazing animals had long since deserted it. Rustenberg Girl’s High, the school Judy attended, was opposite the Common.

In my first year at school I recall buying ‘frozen suckers’ for tuppence from an Indian owned corner shop close to school and eating them sitting on the grass in the Rondebosch Park while looking at the mountain. A few years later with Apartheid tightening its grip the Indian proprietor was forced to sell. Some of my conservatively minded English Speaking schoolmates, whose parents probably supported the opposition United Party tepidly opposed to Apartheid, discreditably seemed to welcome this.

The private boys’ school Diocesan College, commonly called Bishops, who were our main rivals at rugby and cricket was also close by. Private schools were not contradictorily called ’public’ as in England. Later years before the demise of Apartheid, Bishops ignored and challenged the Nationalists Governments policy by accepting some pupils who were not white.

After Apartheid’s demise in the 1990’s, privileged government schools such a RBHS took in pupils of all races. The new ANC Government in effect made them almost private schools as the pupils’ parents had then to pay the teacher’s wages. Coloured and African children with wealthier parents could then attend them - wealth rather than race discriminated access except for a few scholarship pupils.

To me school’s rugby was perhaps more important than any other activity including academic lessons. It was virtually compulsory except for those excluded on medical grounds usually playing hockey. At senior schools there were 5 age groups for rugby - under 13,14,15,16 and 19 and in each category there were 4 to 6 teams. In the under 13&14 groups there were two weight groups those under 95lbs and those above – I fell into the lighter group, but later this weight division was abandoned – foolishly I think as boys near the age of puberty mature at different rates. All these teams had practise sessions during the winter weeks and competitive matches on Saturdays with other schools throughout the Cape Peninsula and nearby Afrikaans country towns – Paarl, Somerset[5] West, Stellenbosch in wine growing districts.

I joined in with enthusiasm playing first flank forward harrying and tackling the opposing flyhalves, then switched to scrumhalf. I was in the 1st team of all age groups except for under 19 years where I played in the 2nd team. There were more experienced and hardened players in their 2nd and 3rd years in this division taking longer to finish school. I played one or two first team games and journeyed as a reserve player by steam train to play some matches against Eastern Cape Schools. I can still visualise the try I scored – the gap opening as I broke around the scrum, throwing a dummy pass, and then diving across the try line as exhorted by our Captain Vian Morris[6].

.jpg) |

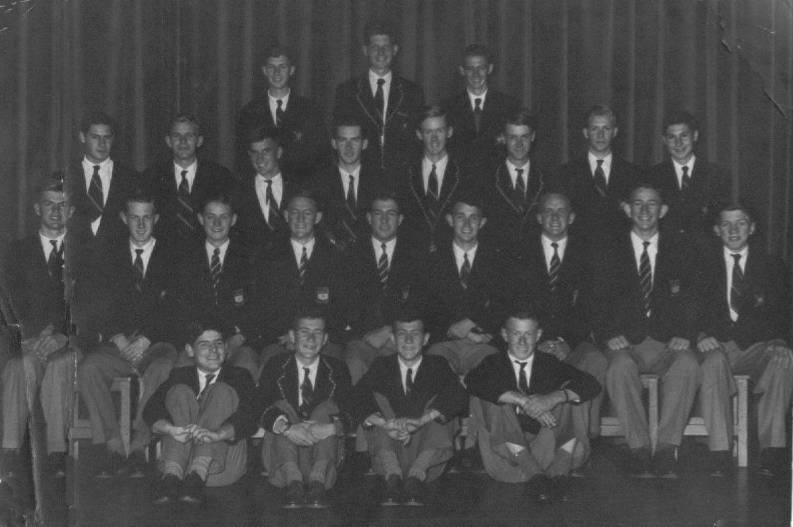

Team coach I de Villiers Heyns with the RBHS under 13 year / under 95 lbs side. I am at top left |

The most memorable coach was in my first year was I de Villiers Heyns - know to all as Tinkie. He was not a teacher at the school but was then about 25years old back from an athletics scholarship in the USA and still studying at the University of Cape Town. He had imaginative ideas and could convey his enthusiasm. He had been a Springbok half-mile athlete, and was later to become a Provincial Rugby Referee and Professor of Education at Cape Town University. My sister Ruth, taking a Bachelor of Education degree, after teaching for many years, was lectured by him. Tinkie’s association with RBHS lasted for about 60years until his death at 84years of age in January 2009. Except for a few years when away on research in the USA and elsewhere, he was a House Master living and at Mason House - one of the boarding houses at RBHS.

|

|

One of the few games I played for the under 19 RBHS rugby team (scrumhalf giving dive pass). This game was at Newlands on 28th August 1954 (my last year at school) against Hottentot Hollands High. The referee in white is Tickie de Jager a long serving master at RBHS. Our captain Vian Morris is standing just behind me and Beverley Dixpeek is on the left |

Fortunately I suffered no serious injuries during schools rugby other than regular bloodied noses, I ignored this and continued playing dripping blood[7] until it clotted. But at least 3 boys I tackled in mid week practises suffered knee and shoulder injuries putting them out of action for several weeks.

After matches we stripped and took cold showers, no hot water was available. There was little concern about being nude in front of team mates.

The school’s pupils were largely dayboys, but also had a significant number of boarders from up country districts with a few from Rhodesia as well. Some boarders were from Afrikaner farms and were physically more mature contributing significantly to the strength[8] of our rugby teams.

In each year there were four classes with about 30 pupils. Each class followed a different set of at least 6 subjects, included compulsory English and Afrikaans (lower grade for English speakers). No other languages African or European, except for Latin, were available for study. Pupils were graded into classes according to their ability. The brighter pupils, in whose class I found myself, generally took mathematics, physics and chemistry, and Latin in their final year whether or not their interests really lay in those fields. Subjects such as history, geography, and bookkeeping were irrespective of their merit or interest generally taken by less academic pupils. Latin was still rather unnecessarily required for pupils who intended studying medicine or law at university.

Initially I did quite well in class examinations coming about 4th or 5th out of 120 boys in my first senior school year. It was a challenge to establish were one stood, but as I proceeded I paced myself and took studies less seriously. Becoming more involved with sport, I dropped down the rankings to about 20th.

All teachers were involved in sporting and cultural activities such as athletics, cross country running, cadets, debating societies etc, seemingly happy to spend their non teaching hours on this. I rather bizarrely started high jumping – I was far too short but enjoyed doing the ‘western roll’ (now not often used) jumping horizontally face down over the bar – my scrumhalf dives had made this easier. I did not participate in occasional evening activities such as the debating society because of lack of transport – cycling at night on ill lit roads was considered to be too dangerous.

School cadets were compulsory and for these we wore sensible khaki shorts and shirts – more suited to the climate than our normal uniform of warm navy blazers, grey flannels and felt hats. Marching and a little arms drill was about all we did – some boys joined the band blowing bugles and beating drums. At an annual parade an outside military official inspected us. Once he did not show up so our old retired Latin Master, Mr Munday, who had headed our cadets at one time, was roped in at the last minute to inspect us – all went well, but the stress must have been too great as unfortunately he died that night of a heart attack.

I still remember a school outing climbing Woody Buttress one of the Twelve Apostles heads on the west side of Table Mountain overlooking the Atlantic Ocean glimmering several thousand feet below. About sixty pupils under the leadership of our teacher ‘Doc’ Watson[9] scrambled up this simple climb. During any return visit to Cape Town I usually climb up the mountain. Mr Watson took us for English and his lessons were always interesting in that we covered a large range of topics sometimes touching on politics – usually a taboo subject. He also took Latin – a subject which I found boring – especially the weekly homework. Sometimes, too tired to do it, I cribbed if from friends just before the lessons started.

I passed my Cape Senior Certificate at the end of 1954 with the matriculation exemption required for university entrance.

|

My final year in 1954, in class E1 at RBHS. I am second row from top, 3rd from left. |

25 years later in 1979, during my return period in Cape Town from 1972 to 1980, I attended a reunion dinner of our matriculation class and teachers. Some pupils had physically aged, others appeared virtually unchanged, teachers had shrunk and we now saw them as ageing mortals not leaders to whom one had once deferred. Several pupils who had emigrated did not attend. One of them wrote his school day reminiscences from Canada and recalled that I had frightened teachers with ammonium nitrate explosions and tried to shock them with electric cables attached to doorknobs. I have no knowledge of these allegations.

.jpg) |

25th school reunion - me about 41 years old with Georges Delpierre, Gary Freeman, and Steve Campion |

At the next 40th year reunion dinner in 1994, to which I journeyed from England, the grim reaper had claimed many of the older teachers and some of the pupils. Tinkie Heyns remained his youthful self and gave an after dinner address where he diplomatically advised my fellow ‘Old Boys’ to accept and adjust to the new political reality in South Africa. Another teacher, Charlie Halleck, who had been notoriously ragged by his pupils, was now well into his eighties but remained mentally sharp. He was well informed on the five nations rugby results in England. My youngest son Benjamin, in his twenties who was just finishing his studies at the University of Cape Town talked with him about philosophy at a ‘braaivleis’ organised for old pupils of my year and their families.

Norman Grimbeeck, with whom I had attended primary school at Pinelands before going to Rondebosch, was there with his full head of flaming red hair, John Benn also, who had played rugby as flyhalf in many schools games with me. Georges Delpierre, who led us later as university students up Wit Els Kloof from Mitchel’s Pass to the top of Waaihoek peak was there. Steve Champion, an accomplished cadet bugler, who I had sat near to in class, was still a keen sea angler.

Our fiftieth reunion in 2004 was interesting in that the school was now well integrated with privileged children of all races attending. I espied Whites, Africans, Coloureds, Indians and Chinese in the large green and luscious playgrounds. Effectively the school, now funded by parents as well as the state, was a private school. I was amused to see that pupils, incongruously in my opinion in a warm climate, still dressed in heavy blue blazers and short trousers. Further my class old boys, who attended the celebratory dinner with their wives, wore old school ties and blazers – only about 5 class mates, including me, wore only open necked white shirts – unconscious rebels or lacking in decorum?

Our sixtieth reunion in 2014, organised by John Benn, Bob Blyth & Eddie Lockyer, included a tour on 13th March of the school and dinner with wives - the numbers of E54 Old Boys had thinned down somewhat from previous reunions. The School looked pristine and had grown hugely in academic, cultural and sporting pursuits. Attached are a few pictures of this memorable occasion.

.jpg) |

| Fallen Old Boys in two world wars, remembered in the Memorial Hall, where we gathered before a tour of the school |

.jpg) |

|

Old Boys & wives photographed in front of the memorial to Tinkie Heyns (see notes about him in sections above) |

.jpg) |

| Old Boys, wives and staff In the Chris Murison Centre - named in honour of Mr C B Murison - Headmaster 1986 - 1997 |

.jpg) |

| Playing the game |

[1] Now called the ‘blue school’ because of it’s uniform to distinguish it from the ‘red school’ opened a few decades later

[2] An Afrikaans word translating as ‘frog’ in English

[3] With double decked bunks to increase capacity

[4] Later, when we returned after a 13 year stay abroad and lived in Wynberg for eight years from 1972 to 1980, two of my daughter Karen and Andrea, also attended W G H S

[5] Named after a Colonial Governor at the Cape – Lord Charles Somerset. Ironically many Afrikaans towns in the Cape were named after important Englishmen – in my youthful ignorance I thought these to be Afrikaans names

[6] His parents and my parents were friends. Vian was a talented sportsman playing soccer for an outside club in addition to rugby at school. He and a brother were also good cricketers.

[7] There were no blood bins in those Aids free days

[8] After the demise of Apartheid in 1990 some African boys strengthened the rugby teams still further.

[9] Doc Watson died with several other adult climbers in the nineteen seventies when on a rather more difficult rock climb on Table Mountain, on the Newland’s side. He had attended Bishops as a boy and served with S A forces in the 2nd world war in the North African dessert.

index memoir - homepage - contact me at