index memoir - homepage - contact me at

My first memory of my maternal grandparents is at their house in Johannesburg during a visit with my mother when I was 4 years old in 1941. My sisters attending school had remained behind in Cape Town with my father. I retain a blurred picture of my Afrikaner grandmother Cecelia Johanna (nee Kritzinger) - called Poppie, standing, large and pale, warming herself in front of a coal fireplace, and complaining to my mother of eczema. My grandfather Harold Barker was awaited at home from his work as a court stenographer in Johannesburg.

|

|

|

|

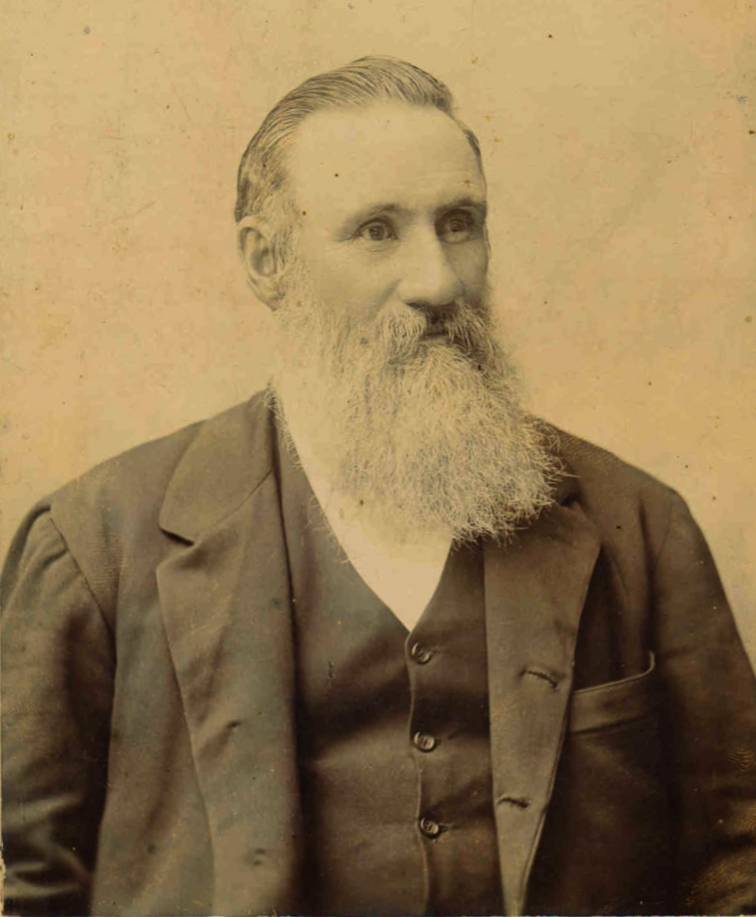

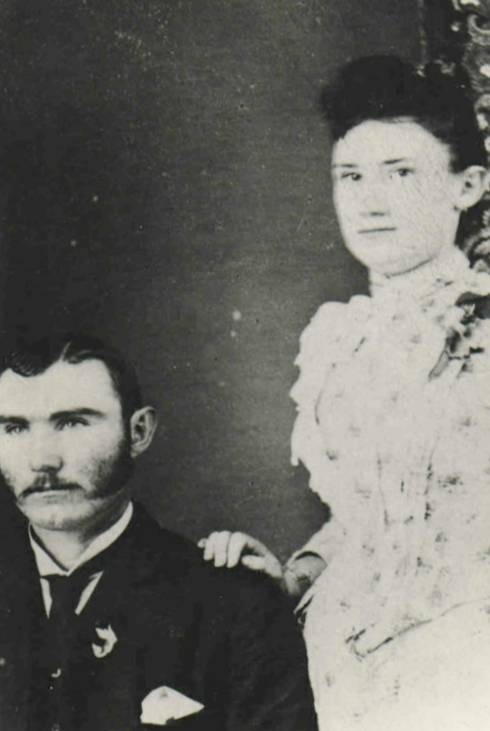

Anne Maria Cripps (born 1852 in Blackfriars Canterbury) wife of Alfred John Barker (see pictures below) and mother of: - my grand father Harold James Barker and his brothers my great uncles Stanley and Alfred Ernest (all troopers in the Boer War in centre picture) - their pretty sister Katie Barker born 1888 (shown on picture on right) died of diabetes at 21 years. Anne Maria Cripps had 9 children - a few not surviving into adulthood |

||

I remember the garden with tall trees, a large netted run filled with clucking fowls, and stepping into it - shit squeezing between my bare toes.

Peering through an open gate onto the road I saw a black van passing. The back door opened and several African youths sprang out and started running away, two white policemen laughingly gave chase, catching them and putting them in again and then drove away. The whole cycle repeated itself several times with both the detainees and policemen seeming to find the situation highly amusing. Things became less funny in the years to come.

Lizzie and Alie were my mother’s two older Afrikaans half sisters. Their father, a Coetzee, had apparently died after the Boer War from his wounds, before London born Englishman Harold arrived[1] on the scene. The sisters were both married and still lived on the Witwatersrand. We visited one sister, the wife of a gold miner, in the dusty town of Brakpan (bitter pond) which seemed to consist of ram-shackled rusting corrugated iron houses surrounded by creaking steel windmills trying to pump up water.

|

|

|

|

|

My mothers family - 1st picture: wedding picture 1st July 1904 of Harold James Barker and Cecelia Johanna (Poppie) with her two daughters Alida and Elizabeth Coetzee and Harold's father Alfred John Barker (white moustache) - 2nd picture: my mother Bonnie flanked by younger brothers Jim and Alfred with half sisters behind - 3rd picture: my mother in school tunic with brothers - 4th picture: family portrait |

|||

Later when I was about 12years old, Lizzie and some of her sons drove down to the Cape to visit us. They took us on a picnic in their smart black Citroen car to the Palmiet river mouth on the mountain road along the coast from Gordons Bay heading towards Kleinmond. We swam and played in the vinegary brown mountain stream pond behind the sand barred outlet into the sea. A real treat as such spots were not easily reached.

My grandfather Harold Barker retired after my grandmother, slightly older than him, had died. He sold his house and came to Cape Town initially staying at our home in Pinelands. He occupied my bedroom and I moved in with my sisters. His car was a fascinating object often left unlocked on our driveway. With a neighbourhood friend I pretended to drive it turning the steering wheel and sliding below windscreen level when pushing the distant floor pedals. Grandpa, as Harold was called, found me doing this and ejected me – I was ashamed and resentful. After some months he moved to Hermanus, a small but fashionable coastal holiday town backed by pretty mountains, some 100km from Cape Town.

|

|

My grandfather Harold James Barker 1876 to 1956 as I recall him in my youth |

He bought some trucks and started a cartage and construction business[2], eventually building about five houses. He remarried, and much to my mother’s annoyance, repossessed some of the furniture given to her after my grandmother’s death. Relationships became strained and we saw little of him. Ironically my mother replaced an oval dining table with a large shabby rectangular farmhouse one on which we could then play table tennis. We only realised later that it was made of much prized local yellowwood and was quite valuable.

After about 10 years, my grandfather’s business failed, he and his second wife separated. He returned to Cape Town in 1955 and lived in a room in a private house just below Mosterts Mill in Mowbray and started painting watercolours. One Sunday he went to Milnerton to watch his landlord and wife horse riding on the sandy beach. Recalling his horsemanship during the Boer war as a dispatch rider, he decided then, at 79 years of age, to ride again. The horse bolted, he fell off, was dragged with his foot caught in a stirrup and died of a heart attack. My father appeared shaken after formally identifying his body. I attended my first funeral as a pallbearer in the new St Stephens Church in Pinelands. He was interred in one of the Woltermade cemeteries stretching endlessly in the sandy Cape Flats along a railway line – anonymous and uninspiring burial places.

After his death Ernest Barker my great uncle, Harold’s older brother, a more sympathetic person, continued travelling between Cape Town and England on Union Castle[3] boats to escape English winters and to visit his children who had immigrated to the Eastern Cape after the Second World War. I remember meeting him once in the Gardens near the museum and St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town. His fingers were distorted with arthritis and I now see the start of similar decay in my hands.

Added in September 2009

As a child I did not really know much about my Afrikaans grandmothers family but have recently received information and photographs from Nigel McLean, my late sister Judy's husband.

|  |

| My great grandparents (my grandmother Cecelia Johanna parents) - Louis Jacobus Rudolf Kritzinger 1843 - 1917 and his wife Rachel Jacoba Elizabeth Coetzee 1844-1906. They had 3 sons and 4 daughters. Louis was a farmer in Natal and also a big game hunter -see newspaper article below | |

|  |

| Cecelia Johanna with her eldest brother Pieter Hendrik Kritzinger | One of Cecelia Johanna sisters Cornelia Gerharina Jacoba Kritzinger - born 1878 - mother of the famous Comrades Marathon runner Wally Hayward (my mother's cousin) |

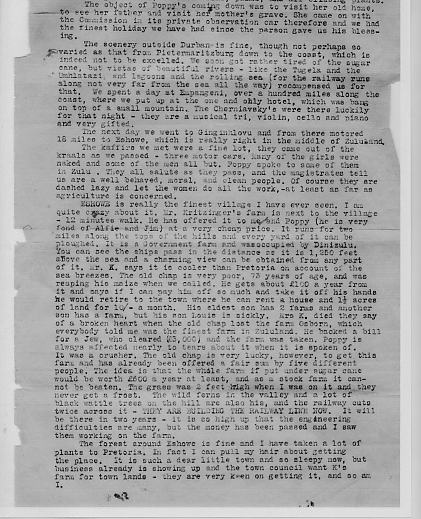

My grandfather Harold and his wife Poppie (Cecelia Johanna nee Kritzinger) visited her widowed father Louis Jacobus Rudolf Kritzinger when he was 73 years old at his farm in Eshowe in Natal in about 1916 about one year before his death. Harold who was by profession a shorthand typist recorded this visit and a scan of his typewritten record is attached:-

|

From a Johannesburg newspaper 1919?

The exploits of one of the best-known hunters in this country were recalled in a Johannesburg sale-room last week.

He was Mr Louis J Kritzinger, affectionately known for years in Zululand as “Oom Louis”. Mr. Kritzinger died on his farm at Melmoth - which originally belonged to the Zulu king, Cetewayo - three years ago, aged about 76.

Mr Burchmore, the city auctioneer, disposed of a farm in the old hunter’s estate on Wednesday - the property “Houtboschrand”, situated in the Lydenburg district, and adjoining the Sabie game reserve. This was the scene of many of Mr Kritzinger’s shooting exploits in past days. At the Sale, “Houtboschrand”, which is over 3,900 morgen in extent, realized a price averaging about 4s per morgen. The district where it is situated is described as ideal cotton country.

The place was acquired by Mr Kritzinger forty years ago, and he kept it for hunting purposes. He used to trek there from Zululand, crossing the Lebombo range into what is now the game reserve, in the course of his shooting trips.

It is recorded that on a certain trip he shot 15 elephants in one day.

The tusks he afterwards loaded on to a wagon and transported them to Durban,

Everybody knew “Oom Louis” in Zululand. His homestead in Melmoth was ‘liberty hall’, where acquaintances frequently gathered and at weekends stories of his hunting days were related.

“Oom Louis’s” encounters with lions as a young hunter furnished thrilling episodes in the reminiscences. Once he had to lie out storm bound, and had lost his gun. He was roused from sleep by the growling “gouf!” of a startled lion, which pawed suspiciously in his direction, but fortunately bounded off after he sat up stock-still. Similar experiences not less thrilling formed a fund of oft-recounted stories in his declining years.

“Houtboschrand” is one of the farms which some time ago were cut off from the Sabie Reserve for settlement purposes as potential cotton properties. It still teems with game.

My mother said that her younger brother James Barker (Jim) while still in his Afrikaner mother’s womb sailed to England. This voyage assured that her father Harold, a soldier for the Empire in the Boer war and a jingoist, had at least one English son and not all colonial South African children[4]. Jim was born in London in 1910 and returned and grew up in South Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

1st picture - Jim born 1907 on maids back. 2nd picture - older brother Alfred flanked by Jim (with pipe) and friend. 3rd picture - Jim at right (in South African forces in 2nd World War) at Pyramids. 4th picture - Jim in Italy |

|||

In the Second World War he served in North Africa and Italy with distinction being awarded Military Cross for bravery. In Italy he was inflicted by a plague of boils but was otherwise unscathed. He was my mother’s second brother, the eldest Alfred Kritzinger Barker died of black water fever[5] in 1938 when prospecting for gold in Kenya.

I first met Jim in Johannesburg during our visit from Cape Town in 1941. Although only 4years, I have vivid images of this visit. Jim was dressed in uniform on leave from the South African army. He was planning to marry his first wife Louie who was not well liked by our family. I recall earnest walks and discussions between my mother and Jim in a wood. But he married and a divorce followed later. After the Second World War he settled in Rhodesia.

In 1949 as an unaccompanied twelve year old, having just finished junior school, I visited him in Umtali in Rhodesia. I obtained a South African passport and left Cape Town by steam train climbing slowly upward through the vineyards in the Hex River Valley Pass onto the Karroo semi-desert plateaux. The journey on narrow 3 foot 6 inch track took four days and three nights compared with several hours flying time today.

We passed through Mafeking (of Baden Powell siege fame in the Boer war) and then sliced through northeast British Bechuanaland[6] - later to become Botswana as an independent state. Passenger railway coaches were of wood and compartment seats were covered with durable green leather – a good surface in a sweaty climate. At night four further beds were folded down from the walls and with the two seats, six beds were made up in each 2nd class compartment[7]. We stood on the open balconies at the end of coaches trying to cool down in the wind. Coal smuts from the puffing engine flew into my eyes as we gazed ahead at the scenery - usually monotonous miles of dry scrubland and koppies, flat-topped hills, in the distance. This also gave temporary respite from my companions especially a passenger who rather than swallowing black grape skins spat them into the open compartment refuse bin some distance away.

We ate leisurely meals, costing about half a crown[8] in the dining saloon. We sat at white clothed tables with a full complement of silver cutlery with a view on both sides of the train. We started with a soup, continued with steamed fish, a meat course with vegetables and finished with a sweet and coffee – all this made by chefs in a rocking galley, and served in heavy monogrammed crockery by ‘white’[9] waiters dressed in black trousers and coats. Pre- prepared airline type dishes had not yet been conceived.

At night I sometimes awoke when there was no movement to find us stopped at a station in a vast emptiness.

We chugged on to Salisbury in Southern Rhodesia, a British colony. At Salisbury I changed from South African Railways onto Rhodesian Railways and journeyed through brownish scrub country on to Umtali close to the border of the Portuguese colony of Mozambique. Black Rhodesian cabin attendants with musically spoken English replaced the harsher clipped accents of the South African crew.

Childless Jim and Margaret, his English born second wife, met the train at Umtali and we returned to their smallholding. My bedroom was a thatched rondavel (round thatched roof hut) separate from the main house lit only by candles. I slept with the door closed but unlocked close to the black servant quarters - there were no security problems at that time in Rhodesia. The short lived Central African Federation of Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland had not yet been formed and disbanded. Mr Ian Smith’s unilateral declaration of independence from Britain and the following African guerrilla war seeking freedom and African majority rule was also well in the future.

Although Rhodesia had no ‘apartheid’ legislation, the segregation of races and facilities in Umtali (and presumably the rest of Southern Rhodesia) seemed to be even more severe than in my hometown. In more ‘liberal’ Cape Town all races at least had access into virtually all shops whereas Africans in Umtali went to the back door for service and appeared to be poor and downtrodden – probably similar to the situation in other inland towns and dorps (villages) in South Africa.

Most aspects of racial discrimination were present in Southern Rhodesia governed by Englishmen as were found in South Africa where the Afrikaner Boer war Generals Botha and Smuts, converted into staunch supporters of the British Empire, had largely dominated a racially conscious British Dominion – The Union of South Africa since 1910. The discrimination in Rhodesia, however, shattered youthful delusions of fair-mindedness in British colonies.

I was conscious of the dangers of catching Bilharzia, a snail borne disease. After a heavy sustained downpour, 12 inches of rain in 24 hours, Jim noted, when walking about the countryside in the reappeared sun, that there was no danger of wading through numerous little rivulets that had rapidly appeared - Bilharzia snails only lived in still water. Amoebic dysentery was another sickness suffered by Settlers children, but this I fortunately avoided. No medications were taken to avoid Malaria and possibly this area was then free of it. Jim and Margaret kept ailments at bay by downing three or four double whiskeys every evening while practising their golf putting on the sitting room carpet.

We drove by car to Leopards Rock in the Vumba Mountains not far from the borders of the then Portuguese East Africa. Some Settlers had built elaborate houses or castles to which they would have aspired in England but probably not realised - an ‘Indian Hill Station’ in the midst of Africa to relieve them from overheating and to remind them of ‘home’?

I returned to Cape Town having no recollection of the return journey – the route had lost its novelty. The holiday had been interesting, but I did not feel very close to either my uncle or aunt who possibly found me, a child not their own, rather strange.

The next time I saw Jim and Margaret was 10 years later in 1959 in London when they were over on holiday. My wife Cubby and I had recently come to England and were living in a few rooms in a house at Muswell Hill. Our first daughter Nicholette had just been born in the fantastic ‘Indian Summer’ of 1959. When locals remarked that the weather was good we agreed thinking that it was nothing unusual - it was similar to a normal Cape Town summer. In following years, when little sun appeared, we realised it had indeed been exceptional.

We attended a cocktail party given by Margaret’s sister, a Londoner, and invited Jim and Margaret for Sunday Lunch. During the meal, which was one of the first Cubby had prepared for guests, the conversation unfortunately turned to Southern Rhodesia. I mentioned that the Africans would at some stage have to be given political rights and discrimination ended. Jim, flushed with our cheap half crown[10] cider, was incensed and declaimed about the uselessness of ‘munts’ who would never reach the level of ‘civilised’ white men. In my youthful idealism, having just left South Africa’s Apartheid state where similar nonsense was legislated, I protested. My rebuttal of their prejudices offended my guests and we parted on strained terms and were never to meet or communicate again.

Jim and Margaret returned to Rhodesia and started raising pigs on his smallholding. He later became a Senator in Ian Smith’s illegal Rhodesia Front Government. After the guerrilla war defeating Ian Smith’s regime, Mr Mugabe[11] took control as Zimbabwe’s first African president. Jim and Margaret, presumably because of their age did not join the exodus of whites to South Africa, but remained and died in Umtali (now called Mutare) in the early 1980s. Margaret, shortly before her death, inherited some money from her English family. This money passed on to Jim and later on his death to my two sisters. He bequeathed his war medals and decorations to one of his half sisters sons. I, his closest living male relation, had been left out of his will

My father, William Anthony Allsopp, was born in 1899 in semi-tropical Durban, Natal on the east coast prior to the Boer war and the Act of Union in 1910 when Natal became part of the self governing dominion the Union of South Africa changing it’s colonial status. His father Lawrence was the son of a Methodist Minister in Durban whose family had come from Derbyshire. His mother Annie Sykes was the daughter of a Yorkshire man who had become a sugar baron in Natal. Annie, as a woman inherited £1000 on her father’s death compared to the £19000 bequeathed to each of her four brothers, considerable sums in the eighteen hundreds - naturally the will was not challenged.

|

|

|

|

1st picture - my great grandfather William Sykes 1839 to 1915 (sugar planter married to Elizabeth Ingram 1844 to 1902 - no picture). 2nd picture - my great grandfather Methodist Rev. John Allsopp 1837 to 1927. 3rd picture - his widow Elizabeth (nee Selby) 1839 to 1938 (second from right front) with some of her nine children including (on far right) my grandfather Lawrence Vivian Allsopp. Two of her children died in infancy. |

||

|

|

|

|

1st picture - My grandfather Lawrence Vivian Allsopp 1870 to 1954 (Durban businessman). 2nd picture - his wife, my grandmother, Annie Elizabeth nee Sykes 1870 to 1946. 3rd picture - Annie Elizabeth with her three children, Geoffrey, Stella and my father William Anthony |

||

My father William Anthony Allsopp[12] attended Durban Boy’s High School and took French as a subject. Neither Afrikaans, nor Zulu the language of the indigenous inhabitants, was then taught at this school. He recalled as a youth travelling about 20miles in a day by ox wagon to Umhlanga Rocks where they spent their holidays. Umslanga is now a suburb within easy rapid reach of Durban by car.

|

|

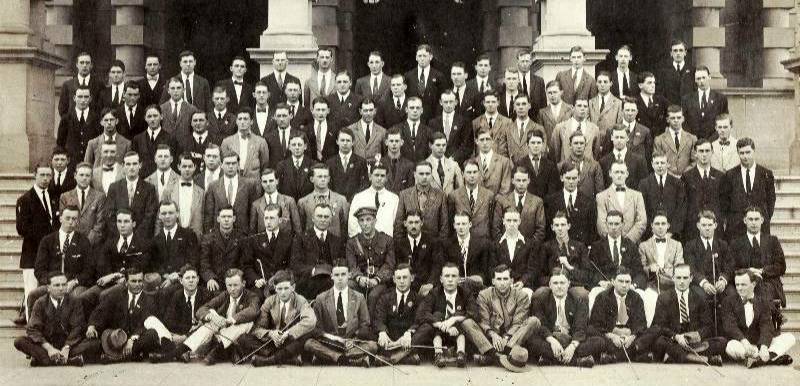

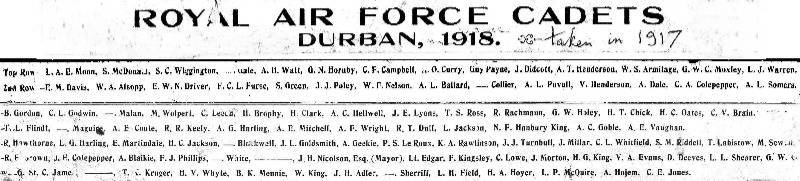

Royal Flying Corps recruits - my father W A Allsopp 2nd row from top, 2nd left |

After completing his schooling, he at 17years of age, enlisted during World War 1 and was posted, travelling by boat up Africa’s east coast, to Egypt for training in the Royal Flying Corps. In 1918 the war finished before an opportunity occurred to die in an air crash or from dysentery[14] - both had killed many of his fellow trainees. His fading sepia photographs of this time show the troopship, the pyramids, the Sphinx and cadets with carefully turned up moustaches nonchalantly smoking cigarettes[15] and floating on the Dead Sea during leave.

|

|

|

|

|

1st Picture - tented camp at Aboukir, Egypt, my father in between two mates. 2nd picture - on camels near the Sphinx. 3rd picture - at Mount Olives in Jerusalem.4th picture - swimming in the dead sea |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

He returned to South Africa after a protracted journey via the Mediterranean Sea, stopping at Marseilles and then London for demobilisation. He did not go to University as his father would not finance it considering commerce all-important. He started working in a shipping agency which was a pity as he was intelligent but no businessman.

|

|

|

|

1st picture- my father 18 years old in his Royal Flying Corps uniform. 2nd picture - brothers in hats, my father Tony left and brother Geoff right yachting in Durban Bay. 3rd Picture - Geoff 2nd from left and my father in hat posing with friends |

||

He found a job in Cape Town on the construction of concrete grain silos for Cape Town’s harbour. Leaving Durban by train, he accompanied a team of Zulus who were also to work on them. The silos were constructed with sliding forms[16] with round the clock working for more than a week. He recalled later, that exhausted he once overslept and was awakened by thumps on his bedroom door, being called to his shift. These tall square silos still stand as a prominent feature near the Victoria and Alfred basins, the old docks in Cape Town and are now surrounded by the Waterfront shopping and entertainment centre built 70 years later, a popular attraction for both local people and tourists.

|

|

|

|

1st picture - staff on construction of grain silos at Alfred Basin, my father 3rd from right. 2nd picture - view of silos being constructed with sliding forms, Devils Peak in the background. 3rd picture - my father on the working platform checking the screw jacks and increments for lifting the sliding forms, flat Table Mountain in the background. |

||

He then worked on the construction of the Steenbras[17] concrete gravity dam for supplying water to Cape Town in the Hottentots Holland Mountains above Gordons Bay some 40 miles from Cape Town. The existing stone masonry reservoirs on the top of Table Mountain had become insufficient for the demands of a growing population. At this time he rode a motorbike from Cape Town to Steenbras. After this project my father joined the Cape Town City Council in their Electrical Department and rose in time to be Chief Draftsman designing related building and civil works. In his late forties, after part time study, he wrote and passed the Institution of Structural Engineer’s examination and thus qualified as a Professional Engineer. He followed this with a Diploma in Architecture from Cape Town University again by part time study.

In the 1940’s, whilst working for the council and prior to qualifying as an Architect, he had designed several houses for private clients. An imposing house, built in Hermanus on the rooks overlooking the sea, was still standing in year 2000 when we passed through. He retired from the Cape Town City Council at 55years and then worked for firms of architects until he was 74 years of age, a record which I being unemployed in England at 62 years was unable to emulate.

In his early fifties he became a teetotaller. After joining Alcoholics Anonymous he broke a compulsive habit of drinking copious quantities of spirits daily at home and at lunchtime at work - he never drank beer, the drink favoured by sports spectators, as far as I can recall. He brought bottles home on public transport hidden in a Gladstone bag or brown paper packets. Brandy and ginger ale, and gin and tonic, were drinks favoured by my parent’s generation, imported whisky was too expensive. South African ‘sherry’ was seldom drunk and table wine was often of a poor quality at that time. Sweet and sickly wine fortified with alcohol was sold to coloured people with unfortunate social effects.

My father continued chain smoking about 60 cigarettes[18] a day until his late seventies. Many burnt out, barely inhaled, in an ashtray as he worked on his drawing board. At home parents were seemingly unaware of potential dangers of passive smoke inhalation by their children. My father, however, well before later cancer scares, warned us of the possible dangers of smoking - he blew smoke into a tissue showing the yellow gunge which he said would obviously clog up lungs. Ignoring his own advice, he persisted in smoking. Some years before his death he survived a near bursting aorta, but emphysema made his last years miserable.

He married my mother when he was 33 years old and she 27 years. In their early years during the global depression they stayed in some of the original army housing quarters provided in the first war in Camps Bay. Camps Bay was then linked to Cape Town by railway tram with steep mountain gradients and switchback bends over Kloof Nek (lying between Table Mountain and Lion’s Head). The trams had been removed before I visited there as a young boy but the camp, where some of my parents friends still lived, seemed idyllic on the mountainside amongst the natural fynbos[19], overlooking the white sandy beach, fringed by brown granite boulders. Later as children came my parents moved to Claremont.

My father after moving down to Cape Town, had little contact with his parents in Durban where he had been born. He only paid one visit there over 50 years later when he was eighty years old and his parents were long since dead. That was his first flight in a commercial passenger aircraft[20].

My father’s younger, likeable, brother Geoff, a keen rugby and cricket player in his youth at Durban Boy’s High School and afterwards, was an extrovert compared to my father. He paid us several visits from Durban. On one occasion he took us on a tourist bus tour around the Cape Peninsula – parts of which I had not seen before. We stopped at a farm store in Constantia and bought bunches of purple grapes which I greedily devoured and then threw up at the end of the long hot day.

My sisters, Ruth and Judy, when in their teens, visited Durban on separate occasions. They stayed with Geoff, his wife Nita, and his two sons David and Larry. They met their widowed grandfather, Lawrence Allsopp, for the first time. Ruth became friendly with Geoff’s youngest son Larry who in turn visited Cape Town. David the eldest son was a nervous person who had apparently failed to live up to his father’s unrealistic high expectations. Larry who had attended a private school in Natal (based on the English Public School system), and despite his father’s service abroad with the allied forces in the 2nd world war, was for a time attracted by fascism and contemplated adopting a Germanic name – whether this was a pose or sincerely believed was not clear. Some years later at 33years of age, after a game of tennis, he complained of being tired, and went to lie down and died of a heart attack. He left a wife and children on whom Geoff doted.

When we left the Guangdong Nuclear Power Project in China in 1989, we passed through Durban and saw Geoff then in his late eighties. He had moved into a spartan room in an old age home. He had just recovered from a bout of pneumonia and had given up jogging, a lifetime passion for which he was well known in Durban. He clearly recognised my wife who he had first met 30 years earlier just after we married and whose appearance was not greatly changed. He obviously could not place me, his near bald white bearded nephew who was very unlike his once young dark-haired clean-shaven, trimly moustached brother, now dead.

We first met Stella, my father and Geoff’s eldest sister, after we had moved to London when she visited some relations in Derbyshire in the early 1960’s. Later during our return stay to Cape Town between 1972 and 1980 we were to meet both Geoff and Stella again when they visited. Stella older than her two brothers outlived them both dying in her 90’s.

Panting with exertion and flushed with excitement the little fellow burst into the living room of the old ranch house.

‘Grandpa has caught a dragon’ he cried.

His mother Annie and aunts were too engrossed in their afternoon chat over cups of tea to pay but scanty attention to the excited little boy.

‘Mommy’ he insisted, ‘Grandpa has caught a dragon and he has tugged it to the stables’

It was one of those blistering hot days in December 1904 when the clay surfaces of the wagon roads were parched and cracked in an almost regular network by the fierce rays of the sun.

My grandfather, on returning from his daily rounds of the cane fields on horseback, had found a large python lying swollen and gorged from a meal of a small buck it had engulfed.

Rendered inactive and defenceless it was an easy matter for him to slip a rope noose over it’s head and ride the remaining half mile to the stables, dragging his victim.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Each year during the Christmas season it was customary for my mother Annie to return with her children to her father’s estate for a holiday. My father Lawrence Vivian Allsopp[22], a businessman in Durban had married Annie Sykes, the eldest daughter of a sugar planter. In those early days these private sugar estates each had their own mills producing their quota of brown unrefined sugar.

My grandfather William Sykes, a pioneer Yorkshire man, had arrived in South Africa with his bride. At first he was engaged in transport riding and then invested his small capital in the rearing of ostriches. Prior to the slump in the feather market he sold out and purchased acres of cane lands on the Natal coast.

Sugar Cane Planters like my grandfather required a large number of labourers. The most convenient source of labour appeared to be from Zululand, but Zulu men in those times still regarded themselves as warriors and disdained to perform such menial work[23]. The Natal government overcame this problem by indenturing Indian men and their wives - the Indian population in South Africa largely arose from these roots.

My grandmother Sykes is but a faint memory. She was an Irishwoman, a slight dark woman of considerable beauty whose delicate health was undermined by rearing many children in pioneering conditions - four sons and four daughters. My mother Annie was the eldest child and the rest of the family followed at frequent intervals. Suffering from ill health my grandmother died when I was little more than a toddler.

My sister Stella and I were both born on Trenance Estates in the old homestead. But we moved and then lived in my father’s rambling house on the outskirts of Durban. It was here that my brother Geoffrey was born. We were fortunate in that our home stood on a large plot with numerous indigenous trees and was planted with tropical fruit of many varieties – a paradise for children. However, in spite of these idyllic surroundings we looked forward with excitement to the annual visit to the plantation. In our eyes this was vast and limitless – full of adventure and interest.

My grandfather was in the nature of a patriarch, and as each of his sons took a wife, a home was built on the estate for him. Eventually the old home became the hub of a small community consisting of five houses with gardens orchards and stables. Another asset was a tennis court where my mother, uncles and aunts would exert themselves with considerable skill in their leisure hours.

I remember my grandfather as being a man of great age. Powerful and somewhat stocky built with a trimmed white beard and a balding head once with a crop of reddish hair. He had intensely blue eyes which his labourers declared never missed anything. He was a very observant man, and woe betide any employee who shirked his duties, but he was greatly respected and regarded as a just and merciful man in times where harshness of the masters was accepted as a natural thing.

He was very fond of his grandchildren and delighted us with many tales of his past life and adventures. A simple man of little education he none the less had a good head for business and a penetrating insight into character.

He was somewhat of a martinet toward his sons. After their high school education whether from their choice or from compulsion they were strenuously employed on the estate. Each was allocated special duties:

- eldest son, was in charge of the mill and production

- second son was responsible for transport equipment and its repair and maintenance

- third son was responsible for all the livestock included the many oxen for hauling wagons for transporting cut cane from fields to mill. In addition there were stables of carriage and riding horses and other livestock – pigs, mulch cows and poultry.

- fourth son’s duties were principally the ranging of the plantation spending many hours each day in the saddle.

My aunts one by one were married and all but one of them left their childhood home. The remaining aunt stayed with her husband on the estate and was chatelaine of the old homestead until my grandfather’s death.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It was during this period that my happiest recollections occurred and the childhood incident of the dragon remains vivid in my memory.

Our next-door neighbour Rex cut a dashing figure to a young boy of nine years. He had been a Captain in the army in the Second World War, and had been decorated for dragging someone out of a blazing aircraft. He was in his early forties when I first knew him, married with two daughters around my age. He worked as a power tools salesman in Cape Town.

I got to know him when, I fascinated, watched him using electric woodworking machines in his garage. In time I started to help him, catching long planks as he pushed these through his circular saw and planer, and handing him his tools and materials as he made kitchen cabinets, small boats and other items. In the summer months he worked stripped to the waist, well tanned, unselfconscious despite the fact that his staid middle-class neighbours did not expose themselves in this way.

Rex was English, a Londoner, indeed a Cockney, as I found out when his mother in her sixties with her unmodified accent visited him on holiday from England. She mentioned that Rex as a lad had helped break the General Strike in 1926 by volunteering and driving an omnibus. He had carefully lost his Cockney accent and now spoke clear English unaffected by surrounding South African accents. He had probably double barrelled his surname and joined the Freemasons.

With his trimmed, slightly blackened, Clark Gable moustache, clad in a evening suit, he escorted his wife to the socially desirable Kelvin Grove Club in Newlands behind the famous cricket grounds.

His wife was a thin woman rarely seen. She always seemed to be inside the house, a nervous woman smoking cigarettes in an elegant holder. In the afternoon, like a regular Indian memsahib, she took a regular nap to escape the heat of the day and was not to be disturbed by her daughters. One imagined that she only became fully alive at evening social events. She had a close Jewish woman friend whose son was a friend of mine, both schoolmate and Boy Scout. I was shocked when my friend’s father shot himself. Later, when older, I was told that he was apparently devastated by his wife’s infidelity and her intention to leave him.

Rex owned a car, an attraction as we as a family walked or cycled to shops, bus stops and trains. Rex started off with tiny Fiats and graduated via rear-engined Renaults to futuristic looking American Studebakers. Occasionally I would ride in his car with his children and his placid panting, drooling Alsatian dog[24], called Sahib, to Sunrise Beach and frolic in the breaking waves.

Rex smoked heavily at one time he preferred ‘Springbok’ cigarettes. He collected the boxes, empty of their 60 cigarettes, and stored screws, nails and oddments in them - years afterwards these still smelled of strong pungent tobacco. Although complaining of stomach ulcers and taking medicines reluctantly, he enjoyed his glass of whisky. The top of one of his fingers was cut off when using his circular saw when I was not there. Laughing, he told me he had had a drink or two and that it was a stupid thing to do.

During 1952 ‘white’ South Africa celebrated the tri-centennial of Jan van Riebeeck’s landing in the Cape on the 6th of April 1652. An exhibition was built at the new railway shunting yards (on land recently reclaimed from the sea) and I accompanied Rex there to help set up his companies stand.

When I was in my early teens he moved with his family to Rhodesia. We heard some years later that he had died of cancer of the throat. In his last days he had longed to return to the seacoast to catch his last big fish.

Before Rex left he introduced me to another of our neighbours, Dave. He was also a home workshop enthusiast. Dave, who did not talk about the Second World War, had served in the South African Air Force, mostly as a skilled flying instructor but later as a pilot on the Warsaw bombing raids.

He managed a motorcar business selling and repairing cars and owned bulbous American made Hudson Hornets. He installed water injection into the combustion chambers of one of these cars - turning water to steam and hopefully boosting power. His car could travel at a top speed of 100 miles per hour unusual for domestic cars in those days. Later he switched to Nashes. He dextrously converted arcade machines into 16mm cinema-projectors and assembled his own gramophone for playing vinyl ‘hi-fi’ records when they first came on the market.

During one school holiday I helped him build a wooden boat, but mis-measured and made it one foot too long – a good lesson which made me avoid similar errors by always checking twice when I later did surveying work on construction sites.

Before I started my last year at high school, I spent a holiday with Dave, his wife Barbara and their two young children at a house in Hermanus. For a week I stood fishing on rocky fingers projecting out in the sea, watching the waves surge in and break on the adjacent beaches. I frequently cast out my line but the hooks invariably snagged on rocks and I had to break the line as I reeled in. Eventually I caught a fish and we grilled and ate it. Despite it’s delicious taste I have not been tempted to go angling again.

About a year later Dave, as a business sideline, started to harvest seaweed washed up on the sandy beaches of a farm at Kommetjie on the cold Atlantic west coast of the Cape Peninsula and to process this for use as fertiliser. I helped him in this venture during my last long summer ‘school’ holidays before starting at Cape Town University. On the first day, starting in early morning darkness from Pinelands, I cycled, on my heavy battered old school bike, the 30 miles to the farm. With tractor and trailer and four coloured labourers, we collected and loaded seaweed and then spread it out to dry. This was energetic work - the seaweed, if already rotting, was not pleasant to handle. Once dry we hammer milled it into small chips to be used as fertiliser.

For the next two weeks I travelled daily to and from Fish Hoek by train and then cycled to Kommetjie. The combined journey took 1½hours each way. For the last week I pitched a tent in a deserted campsite not being disturbed by anything more than straying cattle. I had prepared badly for this camp forgetting to bring cooking utensils and plates, and eating unheated food from tin cans – a mistake I did not repeat on future climbing and camping trips.

My father, when 55 years old, bought his first motorcar from Dave who then taught us both to drive – sufficient at least to pass our driving license tests. The car was a boon for my evening activities at University, especially the seats folding conveniently into a bed.

Other neighbours unlike Rex and Dave were poor role models. The wife of a pleasant Scottish immigrant had a drinking problem and her screams of anger at her apparently inoffensive husband frequently penetrated the night. On one occasion my father, with his own experience of alcoholism, went over to quieten her down and helped load her into an ambulance. Her condition was possibly linked to the frequent visits of a male friend at lunchtime, my mother observed and depreciated - especially as this visitor had earlier been one of my parents close friends. Many years later I heard that she had regurgitated some food in her sleep and had choked to death.

Another wife of a Scottish immigrant, a sea captain frequently away from home, found it difficult to adjust to the hostile ‘African’ environment and seldom ventured outside the house. She took care to wash all vegetables in very hot water to avoid contamination by microbes - we thought this ludicrous.

Some Afrikaner neighbours, well educated professional people, were fervent supporters of the Nationalist ruling party and must have felt somewhat isolated in this generally English speaking United Party neighbourhood.

The son of another neighbour while studying medicine at university had a nervous breakdown. We would see him as an adult kicking a rugby football in the street – possibly dreaming that he was an aspiring Springbok player – a consoling life of fantasy.

[1] Harold and his two brothers Alfred Ernest and Stanley had come out to South Africa as troopers to fight in the Boer War and he had retuned to SA again after the war. Apparently the Barker clan stemmed from the New Forest ca 1100 where they had been clerks in Holy Orders. Harold's mother Anna Maria Cripps had lived about 98 years until dying in 1950.

[2] His grandfather George Barker had been a builder and architect in Lower Edmonton and at one time owned several houses but lost all but one through gambling.

[3] These passenger liners no longer ply to South Africa, air travel has taken over

[4] Jim’s elder brother Alfred had been named Alfred Kritzinger Barker – Kritzinger being the maiden name of his mother, my grandmother

[5] Chronic Malaria where one passes blood in urine

[6] This rail track was built through British territory rather than passing through the then Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State. C J Rhodes with his dream of a Cape to Cairo railway wished to avoid political obstacles to its implementation. The whole route was never completed.

[7] On long distance train journeys most ‘Whites’ travelled 2nd class – 1st class being more expensive.

[8] South African currency was in Pounds with parity with Britain.

[9] Protected employment was given to ‘Whites’ on the South African Railways at this time.

[10] There was no ‘crown coin’ worth 5 shillings at this time. A half crown was an eighth of a pound - 30 old pennies or 12 ½ pence in today's money

[11] The same President Mugabe who over 20 years later encouraged civil war ‘veterans’ to displace white commercial farmers from their land without compensation and with drastic effects on the economy

[12] My father was always precise in ensuring that his name ALLSOPP was spelt with two ‘L’s and two ’P’s – the same spelling as the once famous beer in England. Whether he was related to this brewing family is not too clear. This brewer apparently became a ‘Lord’ – did he purchase the title? Later there was a scandal concerning dubious information about the real value of assets when he profited from the sale of his business.

[14] Apparently a French doctor seconded to the training camp towards the end of the war saved many trainees affected with dysentery

[15] He started smoking in Durban at the age of 16 years.

[16] Formwork, usually about 1.2m deep, slowly jacked up extended rods so that continuously placed concrete sets at the bottom of the forms before it moves up further

[17] 50 years later in 1976, I was also to work in the Steenbras area on a hydroelectric pumped storage scheme and visited ‘his’ dam. The dam had been raised in height before 1960 to increase water storage capacity. This increased the water forces and overturning moments on the gravity dam wall. So holes had been drilled through the wall into bedrock below and steel tendons anchored in the bedrock and then stressed, increasing resistance to overturning - a rather unusual technique at that time. When I visited the dam I was surprised to see that there were large cracks in the top extended portion of the dam. Apparently a blue shale aggregate had been used for the extension whereas the original lower wall had been built with softer but stable sandstone aggregate. The blue aggregate had reacted with cement (alkali silica reaction?) and severe cracking had occurred which required patching up and sealing.

[18] Cigarettes were often sold in large packs of sixty very cheaply with little tax.

[19] Unique indigenous flora of the Western Cape

[20] He had flown in military transports up to Langebaan north of Cape Town in the 1940’s on occasion.

[21] William Anthony Allsopp – born 15th August 1899, died 9th July 1984

[22] Lawrence Vivian Allsopp – born 12th March 1870, died 1954

[23] Another possible explanation is that wages offered were lower than Zulus were prepared to accept and cheaper labour could be obtained from India.

[24] This placid dog occasionally fought savagely with the bull mastiff owned by my friend Patrick’s family

index memoir - homepage - contact me at